If you’ve ever wondered what chaos looks and sounds like, head out on a Sunday at around 5pm to Avenida Buenos Aires near Calle Eloy Salmon, a few blocks from the general cemetery, and proceed to jump in a bus heading down to the Prado. Sunday is market day, which itself isn’t the quietest environment, but add to that the pushy cars, minibuses and micros attempting to move forward amidst the throngs of people. You’ll will find complete disorder and confusion – or at least the illusion of it. I may or may not have decided to jump in a micro at this precise time and place and dearly regretted it about eight seconds later. The fact that the vehicle was empty and motionless should have tipped me off. Paceños know better.

It’s extraordinary how bus drivers manage to navigate this sea of people, how those same people seem to pay no attention to a five-ton blue machine honking directly into their ears, and how everybody still manages to extricate themselves unscathed. It is a perfectly choreographed waltz in which everyone knows exactly what’s happening around them, where the buses cruise amongst the shoppers and market stalls as if they each had their own predefined routes and risked no danger in brushing against one another. Even more impressive, though, is the moment when the bus suddenly fills up minutes before the traffic starts flowing again. Clearly, I have much to learn because, again, paceños do know better.

This year, 2018, started with protests and strikes erupting from one side of the country to the other, and torrential rains flooding entire towns in the eastern part of the country. The political and social climate is equally overwrought after a recent penal-code debacle and a Constitutional Court decision to allow President Evo Morales to run for president indefinitely despite the popular vote of 21 February 2016 prohibiting exactly that, prompting a new wave of protests in anticipation of the second anniversary of the referendum.

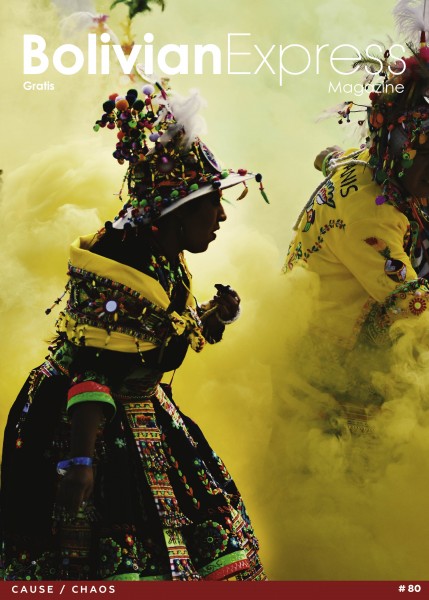

To shed some light on these issues, for the 80th issue of Bolivian Express we want to delve into the chaos that surrounds us, a chaos that is controlled, nurtured and sustained by us – paceños, expats and travellers alike – whether we realise it or not. We’d like to try to grasp the hidden significance that lies behind this tangly mess – like the caseritas stands around Bolivia’s cities, where items are piled in unlikely ways and fitted in the most improbable nooks with a variety of merchandise that will answer to each and every need: a 50-centavo bag of water, a much-needed roll of toilet paper, cat stickers and much more. Even the caserita’s outfit has been meticulously thought out: Each pocket has a specific function, bills go here and coins go there. Because even within the most chaotic mess, order and precision rule.

Bolivia is (in)famous for its culture of protest, the regular strikes and roadblocks crippling the lives of commuters and roadblocks causing hours of delay, but even these follow an inescapable logic. Like matches being lit up, when they feel they have been wronged or an injustice has been committed, Bolivians’ voices are instantly heard loud and clear in the streets. Governments have fallen as a consequence of this popular unrest, laws have been enacted or annulled as a consequence of the people’s indignation. And behind this controlled chaos one can find a very precise, polished mechanism of syndicates, neighbourhood associations and unions that, at their best, safeguard democracy and push the country forward to a more inclusive future.

The plight of the Urus on the drying Lake Poopó

Lake Poopó, once the second largest fishing paradise in Bolivia, has become nothing but an expanse of dry and salty land. The water waned, 30 million fish died and rose to the surface belly up. For weeks the stench stagnated the air. But it is not just the fish that suffered. A large part of the indigenous Urus of Lake Poopó, who lived by the lake for centuries, were forced to leave, joining the world-wide evacuation of refugees who are not fleeing war or a natural disaster, but the devastating consequences of climate change. Facing a desolating situation, they have consequently become ‘the climate change refugees.’

The Urus of Lake Poopó have lived through centuries of displacement due to the forced migration of the Aymaras after the conquest of the Incas, and now the transformation of not only their livelihoods but of their homes. For generations they adapted, but it seems that they will not be able to adjust to the upheaval caused by the drought. Ruth Vilches, officer of Centro de Ecología y Pueblos Andinos (CEPA) tells us: ‘Their way of living has been eroded, they are discriminated against. They used to have their own language but now they only remember some words.’ This, in turn, has endangered their way of living and brings to question whether they will be able to overcome something as consequential and unavoidable as this to remain near the lake.

The Urus are not fleeing war or a natural disaster, but the devastating consequences of climate change.

There was a migration of Uru men to urban areas to work as carpenters and drivers. Some Urus went to the lake Uru-Uru, not as fishermen but as employees of the Aymara fishermen. Many went to work in the mines near Oruro and a lot have also gone to work in the salt mines near Uyuni. Out of the 1,200 Urus living near the lake, around half remain.

‘We were fishermen and that will always be a part of us.’ Don Felix, Uru elder

CEPA, however, is committed to helping them. CEPA, which is the Center for Ecology and Andean Communities, works in defense of indigenous rights, territory and resources. ‘The Uru are in a very special situation, there is no income,’ Vilches says. ‘ They used to live from fishing. They don’t have land. They don’t have another activity other than fishing. So CEPA is accompanying the three communities (Llapallapani, Villa Ñeque and Puñaka Tinta María) helping them replace the loss of their income with other productive activities. Now we are helping the women who want to make artisanal crafts from chillawa, a type of hay [...] but this, in reality, doesn’t provide much income.’ On account of Uru displacement, CEPA has ensured that authorities carry out small projects such as building solar panels and water tanks.

In the region, the Urus were known as ‘the people of the lake’ and without it, they are drastically adapting their way of life. The fishing season began on the shore of the lake with a ritual known as ‘remembrance.’ Around 40 Uru men spent a whole night chewing coca leaves and drinking liquor. Together they recited the names of the main fishing spots of Lake Poopó. In the morning, they made their way among the underground springs and threw sweets in the lake as a religious offering and that’s when fishing season began. Rituals such as this have, unfortunately, become a thing of the past.

Fishing has always been the Uru’s principal activity and dates back generations upon generations. Vilches, who approaches the communities directly and personally, understands that their experiences and beliefs are what makes this indigenous community so special. ‘When we talk to the elders,’ she recalls, ‘they tell us how they lived on their boats. One elder, Don Felix told us: “We basically lived on the lake – I’d bring my little boat – here was the kitchen, here is where we slept… Everything was on the boat.” And I admire them. Don Felix can name 34-different bird species. [...] They were very close to the lake, physically and emotionally.’

According to the elders, ‘the lake always dried up’ but what should have taken 1,000 years took 4 and the difference now is that conditions have changed, it’s not like 40 years ago. This situation may have been easily preventable. Lake Poopó collected a lot of sediment such as dirt, rocks and rubbish from Rio Desaguadero, and as Lake Poopó has no exit, this built up over time – stopping the fish from reproducing. On top of this, chemicals from the heavy metal mines were emptied into Lake Poopó and there has been a severe lack of rain in the area due to climate change, which has caused the lake to dry up. With all these forewarning signs, it’s disturbing that something wasn’t done sooner.

Vilches explains that ‘it was already always anticipated… I imagine the previous and current leaders should have taken actions to prevent the drought. They could have drained and cleaned the lake. They should have foreseen this.’ Recent efforts from the government involved bringing food and materials to the Uru people after the disappearance of the lake. Due the 2013 march for better living conditions, the Uru received one ambulance, schools and homes, but ‘there was still no structural care from the governments,’ Vilches notes. ‘We always knew the lake was going to dry.’

The issues, however, go further than just the lake. ‘Their culture and their social relations and political structures have been disintegrating. There is conflict within the families, between the three communities and with the public authorities,’ says Vilches.

Unlike the Aymara communities of the lake, who all belong to the same municipality, the three Uru communities were separated in 1984 by law, which has prevented them from being unified. The drying up of the lake has only exacerbated underlying tensions between the Urus, having unintended effects such as migration and the disintegration of social and political structures.

Even with these frequent adaptations, Vilches agrees that the Urus are far from losing their identity. ‘This is what surprises me,’ she says. Perhaps there is a silver lining in this situation in that, according to CEPA, even though the Uru have lost their most vital source of income, they have found ways to revive their identity. ‘They are still saying that they are Urus. It’s still present in their way of dressing, speaking and in their attitude.’

Furthermore, with the 2009 Constitution the Urus have more of a public presence, which allows them to strengthen their cultural identity. Vilches adds: ‘I think they have done so already because they have returned to the past. “This is how it was,” they say. “We were like this, our clothes were like this, our relationship to the lake was like this.” Their past is not set in stone, their past is ahead. In a way, their displacement has allowed them to retain their identity.’

Despite current situations, there is still hope for the Urus to remain near the lake. ‘I have the impression that the current rains will improve the water level in the lake and allow the fish to reproduce and the families to stay. I hope.’ The recent rains and the new schools have encouraged them to stay and remain connected to their past: ‘The Urus as a people, as a culture will stay. Their recent hardships have allowed them to reconnect with their past and say: “this is who we were, we were fishermen and that will always be a part of us.”’

Ekeko Lends a Hand

Photos: Georgina Bolam

Each year on 24 January, the people of La Paz head to the Parque Urbano and its surrounding plazas and fill their bags with miniature cars, houses, computers, roosters (we will come back to this one), airline tickets and even marriage certificates. Taking place just before Carnival, the Alasitas festival is a month-long affair, when locals purchase miniature items to give to Ekeko, the Aymara god of abundance, in the hope that he will bring fortune and happiness to their lives. But what are the stories behind the festival, and what do these these miniature items represent to the people of Bolivia?

Ekeko: This is the god of abundance and prosperity in the mythology and folklore of the Aymara people of the altiplano. But even though Ekeko is the traditional god of luck, he must continually be given gifts throughout the year to keep his good fortune alive. To do this, he must be given (lit) cigarettes and alcohol every week, and lots of miniature bits and bobs. According to vendors we spoke to, purchases of Ekeko figurines have decreased in recent years – perhaps because people do not want to be burdened with the effort of replenishing him so frequently, or maybe they just don’t like the smell of tobacco in their house.

Ekeko must be given (lit) cigarettes and alcohol every week.

The frog: Unlike the Ekeko, the frog doesn’t need alcohol or nicotine to stabilise its fortune – it accumulates it all on its own (clever, right?). Keep a frog in your house and be blessed with good luck for all of your mortal life.

The gallo: Well, well, well… Still haven't found your husband or wife to be? Are you still meandering the streets hoping to find your princess or prince charming? Perhaps you are wondering the supermarkets in the hope that your hands will touch over the last tin of soup and it will be love at first sight? Well, look no further… Buy a hen or rooster figurine (depending on preference) and you are sure to find your true love this year. If you are picky by nature, perhaps you want one with a specific job title – a psychologist? A chef? Or, if you are feeling dangerous, maybe even a soldier? Don’t worry, you don’t need to thank me.

Stacks of money: Yes, you read that right. The lottery can be very hit and miss, so here is the next best thing. Just buy some stacks of money at the miniature central bank of Bolivia. This woman will kindly lead you to your correct currency – euros? Dollars? Bolivianos? She has it.

Babies: Feeling broody? They have a variety of babies at the Alasitas. Buy the life-size cot, pram and formula and a real human will come in time.

Miniature tools: Ever needed a mini hammer, shovel or pliers? The mini pliers came in particularly handy when fixing a necklace of mine. They can be very easy to lose, though, so look after them wisely.

Photos: Iván Rodriguez Petkovic

Brewing coffee and culture in Sopocachi’s corner

Sopocachi: an extraordinary enchanted, bustling neighbourhood, with avenues and pathways that weave between the main roads; flooded with ornamental trees, sociable parks where you can have a breath of fresh air within the intimacy of the shaded spaces. In this truly inimitable neighbourhood, and off the Medinacelli passageway, you will find the Café Espacio Cultural Sangre y Madera, a café that triples as a laboratory and cultural space. Víctor Hugo Belmonte, the civil engineer and barista, has made Sangre y Madera his own scientific laboratory. In this café, which has only been open for three months, Hugo puts into practice what he learnt in an international course in Barcelona from Kim Ossenblok, a well-known Belgian barista and coffee taster.

With his wife Kruzcaya Calancha, who graduated in gastronomy, the couple decided to turn their residence into a cultural space. Calancha, also an ex-dance teacher, wanted to maintain the venue as not only a place to eat, drink and relax but also as a cultural environment where workshops of all sorts can take place, such as salsa dancing and children’s theatre workshops. When speaking with the couple, a workshop for women in business was taking place in the main patio area. The environment was inviting and I acquired a sense of a real community that is starting to take shape there. The waiters happily talk to you about the workshops available around the time you are visiting and consistently take pride in the food and drinks they present to you. After my first visit, I have returned a couple of times to simply soak in the atmosphere and try the variety of coffees and appetisers they have on offer.

As mentioned in the menu, it is a house built in the 1920s, once owned by past diplomat and minister, Hugo Ernst. The republican-style house opens with folding doors that lead to the patio of the café. Its windows that almost reach the floor and its cherry-coloured walls come together to create a wholesome experience for the visitor.

Open from noon to 10pm on weekdays and noon to 6pm on Saturdays, anyone can visit to take in the amicable and sociable atmosphere whilst they enjoy some of their favourite items from La Paz cuisine. ‘We have a lot of food and drink that is typical of La Paz – things you would find in the food markets but adjusted for our guests. For this time of year during the Alasitas festival we even have piqueos (appetisers), which we call “Alasita paceña”, named after the festival where locals purchase miniature items to give to Ekeko, the Aymara god of abundance, in hope he will bring fortune and happiness to their lives. You can get a sandwich de chola or salteñas miniature style to share or to have on your own. I was introduced to the sandwich de palta (avocado), which was rich with flavours and tingled my taste buds, particularly with its caramelised tomatoes, soft, fresh bread and basil flavouring.

Although the food is important in this new café, the engineer sees himself, above all, as a lover of coffee. When tasting their coffee I was particularly amazed by the cold brew. Delivered to me in a rotund glass with a circular block of ice in the centre, its delicate sweetness, presentation and delightful coffee flavour was remarkable. This particular coffee is infused for more than 24 hours at 4°C, which allows Hugo to extract the coffee in the most delicate way possible. Others included coffees flavoured with liquors, hot coffees, espressos with milk and their own Sangre y Madera sucumbé with a touch of syrup and toasted marshmallows.

‘Because our coffee grows in Los Yungas [at 400 to 3,500 metres above sea level],’ Hugo explains, ‘it takes longer to mature than other coffees. This simply means it absorbs more sweetness and oils, which makes it one of the best beans available… Preparing a specialty coffee is another world. It is something that cannot be obtained in the supermarket, because there are many variables, such as the handling of the beans, drying and preservation.’ With these elements, Hugo has everything necessary to get the flavour he desires; from an apparatus that measures the consistency of the grain, to a computer application that gives the exact measurement of water and quantity of the specialty beans.

With the introduction of distinctive places such as this, the Sopocachi neighbourhood is creating a new image for itself; an image of experimental businesses, risk-taking processes and diverse cultural spaces for Bolivian and foreign palates.

Download

Download