If you’ve ever wondered what chaos looks and sounds like, head out on a Sunday at around 5pm to Avenida Buenos Aires near Calle Eloy Salmon, a few blocks from the general cemetery, and proceed to jump in a bus heading down to the Prado. Sunday is market day, which itself isn’t the quietest environment, but add to that the pushy cars, minibuses and micros attempting to move forward amidst the throngs of people. You’ll will find complete disorder and confusion – or at least the illusion of it. I may or may not have decided to jump in a micro at this precise time and place and dearly regretted it about eight seconds later. The fact that the vehicle was empty and motionless should have tipped me off. Paceños know better.

It’s extraordinary how bus drivers manage to navigate this sea of people, how those same people seem to pay no attention to a five-ton blue machine honking directly into their ears, and how everybody still manages to extricate themselves unscathed. It is a perfectly choreographed waltz in which everyone knows exactly what’s happening around them, where the buses cruise amongst the shoppers and market stalls as if they each had their own predefined routes and risked no danger in brushing against one another. Even more impressive, though, is the moment when the bus suddenly fills up minutes before the traffic starts flowing again. Clearly, I have much to learn because, again, paceños do know better.

This year, 2018, started with protests and strikes erupting from one side of the country to the other, and torrential rains flooding entire towns in the eastern part of the country. The political and social climate is equally overwrought after a recent penal-code debacle and a Constitutional Court decision to allow President Evo Morales to run for president indefinitely despite the popular vote of 21 February 2016 prohibiting exactly that, prompting a new wave of protests in anticipation of the second anniversary of the referendum.

To shed some light on these issues, for the 80th issue of Bolivian Express we want to delve into the chaos that surrounds us, a chaos that is controlled, nurtured and sustained by us – paceños, expats and travellers alike – whether we realise it or not. We’d like to try to grasp the hidden significance that lies behind this tangly mess – like the caseritas stands around Bolivia’s cities, where items are piled in unlikely ways and fitted in the most improbable nooks with a variety of merchandise that will answer to each and every need: a 50-centavo bag of water, a much-needed roll of toilet paper, cat stickers and much more. Even the caserita’s outfit has been meticulously thought out: Each pocket has a specific function, bills go here and coins go there. Because even within the most chaotic mess, order and precision rule.

Bolivia is (in)famous for its culture of protest, the regular strikes and roadblocks crippling the lives of commuters and roadblocks causing hours of delay, but even these follow an inescapable logic. Like matches being lit up, when they feel they have been wronged or an injustice has been committed, Bolivians’ voices are instantly heard loud and clear in the streets. Governments have fallen as a consequence of this popular unrest, laws have been enacted or annulled as a consequence of the people’s indignation. And behind this controlled chaos one can find a very precise, polished mechanism of syndicates, neighbourhood associations and unions that, at their best, safeguard democracy and push the country forward to a more inclusive future.

Photos: Carlos Sánchez Navas

Social Change Is Noisy and Inconvenient – But the People Will Be Heard

Back in 1981, a New York Times headline declared that ‘For Bolivia, Chaos Rules.’ This referred to the fact that despite constant regime changes, coups and other uprisings in Bolivia, poverty remained constant. But however accurate that was in 1981, Bolivia has changed dramatically since then and the opposite has now become true: The current government has been the most stable since the country’s creation, and Bolivia has Latin America’s fastest-growing economy. However, for those living here today, this 37-year-old headline – taken out of context – still rings true.

Roadblocks, protests and strikes are, to commuters’ frustration, fairly common occurrences, alongside marches on the Prado with fireworks exploding in the background. The end of past neoliberal regimes hasn’t brought the end to this chaos. For instance, on 8 January 2018, Bolivian doctors finally ended a 47-day strike that affected the whole body of medical professionals. Except for emergency situations, medical care was greatly reduced in hospitals and pharmacies. The strike came with continued demonstrations, some of which escalated to hunger strikes. Doctors and medical professionals were protesting Article 205 of Bolivia’s new penal code, which imposed heavy sanctions on doctors found guilty of causing physical harm to their patients.

The last few months have been particularly tense, especially since Bolivia’s Constitutional Court overruled on 28 November 2017 the 2016 referendum prohibiting President Evo Morales from running for a fourth term in 2019. Now he’s free to run again, next year and for the rest of his life. And, with the second anniversary of the annulled referendum approaching on 21 February, tensions and demonstrations are multiplying. Morales’s opponents – as well as his supporters – are planning marches across the nation. Teodoro Mamani, secretary general of Bolivia’s farmers’ union (CSUTCB), is expecting ‘around 3 million farmers to get mobilised in support of the president.

Nowhere else in Latin America have social movements been as influential as they are in Bolivia, where they’ve been – and continue to be – the impetus of social and political change. In 2003, the government of Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada was overthrown due to massive waves of protests, first during 2000’s Water War in Cochabamba and then during 2003’s Gas War in El Alto, both of which brought the masses to the streets, contributing to Evo Morales’s eventual ascension to power. More recently, demonstrations in 2012 against the development of a highway in the TIPNIS region effectively stopped the project.

Nowhere else in Latin America have social movements been as influential as they are in Bolivia.

Protests have become the primary means of political communication between the Bolivian citizenry and the government. Past colonisation and the pillaging of natural resources, followed by neoliberal regimes that only widened the inequality gap, brewed discontent, and the Bolivian people began to rebel and fight for a more representative democracy. When rising prices ignited the Gas War, people reacted against the implicit racism, discrimination and a lack of opportunities that the neoliberal economic system laid bare – just as today people are also reacting to the government’s long and punitive regulatory overreach. Nothing is taken for granted, and what has been achieved so far is only the first step towards a long process of change.

To understand this culture of protest, one can look at Bolivia’s past; marching and protesting are the primary way of political expression against the legacy of neoliberal policy. But this expression assumes many different manifestations. And to really grasp what protest means for the Bolivian people, one should look at the everyday protests; what role the syndicates, unions, neighbourhood associations play; and how they are organised.

In Bolivia, it’s natural for any group of people interacting together for any period of time to join a union or form a syndicate. Because an important portion of jobs in Bolivia belong to the informal sector – juice vendors, caseritas, fortune-tellers, shoe-makers, etc. – workers need to unite to be able to defend themselves and have any legitimacy. A lone vendor would have no chance of survival were he not to join the local association. Wherever you live, you are a part of a junta de vecindario. Each structure is then absorbed by a larger structure with its rules and hierarchy that form an invisible framework supporting the life of the city.

La Paz’s Fejuve (Federación de Junta de Vecinos) is precisely that. It comprises 600 neighbourhood associations and acts as a unified voice for its members. Fernando Zegarra, secretary of Fejuve La Paz, says, ‘We are constantly mobilised…. When something is not working right, the community organises itself.’ Fejuve’s role is to improve living conditions, to fill a social need for neighbours to meet and discuss issues, and to organise marches and protests. ‘A lot of the people living in the laderas are from the countryside and have brought their traditions with them. One of them is the apthapi, and, each time they hold a meeting or organise a march, everybody contributes by bringing food and drinks,’ Zegarra says. ‘That’s why organising marches and protests is sustainable.’

These can be localised actions, such as a handful of people asking for a sewer system in their street, or thousands of people mobilising to protest against a decision from the municipality that will affect them all. Fejuve is a complex but well-oiled all-volunteer administrative machine in which elections take place every two years. Meetings are held weekly, and because of a very efficient chain of command in place, marches can be organised in hours.

What’s happening with the new penal code?

The new penal code was meant to replace the 1972 penal code enacted by the government of dictator Hugo Banzer. It took two years to write and brought some much needed changes to outdated laws. We wrote in BX issue No. 78 about Article 157 of the new code that was going to give access to safe and legal abortions to more women. However, groups protested against a certain number of articles (including the one regarding abortion) and, ultimately, the new penal code was annulled a few days after being enacted. Now the process starts anew and a whole new penal code needs to be agreed on.

23 November 2017: Medical professionals start a 47-day long strike in protest of Article 205 (which imposes heavy sanctions on doctors found guilty of causing physical harm to their patients).

15 December 2017: Alvaro Garcia Linera, vice president of Bolivia, enacts the new penal code after it was approved by the Senate a few days earlier.

9 January 2018: President Morales announces the elimination of Article 205.

21 January 2018: President Morales requests the elimination of the entire penal code so that ‘the right wing will stop conspiring and have no arguments to destabilise the country.’

The reasons for protests or roadblocks are as varied as the people organising them. I once encountered a roadblock on the main highway between Cochabamba and Santa Cruz because the man leading it wanted justice for his murdered father. He claimed that a corrupt judge let his father’s killer go free. On my way back from Santa Cruz, another roadblock was organised by tenant farmers whose land was being sold by the land’s owners. The question that comes to mind, especially if you are the one inconvenienced by a roadblock, is: Are they ever successful?

Oftentimes, they are. That men who lost his father may not have managed to send the corrupt judge to jail, but by blocking a main highway for hours, attention was raised, his and the judge’s names were reported on local television, and his father’s memory was honoured. This is the goal. In La Paz, on avenida Perez behind Mercado Lanza, are a handful of caseritas stands. Because of the insecurity in the area, 10 to 15 of these women recently marched in the centre of La Paz to ask for an increased police presence. The next day, they tell us, the police responded, providing more security in the neighbourhood and converting a once-forlorn and crime-ridden area into a secure and bustling commercial center. For these small associations of people, this is the only way to be heard: block a street, paint some banners, ignite some fireworks.

On the other hand, the extraordinary frequency of acts of protest and roadblocks can lead to officials to not take demands seriously, which pushes protesters to escalate their actions until they are heard. On 25 January and then on 7 February 2018, minibus and micro drivers blocked whole sections of La Paz. Enrique Aliaga, from the bus syndicate Eduardo Abaroa, is leading the second 24-hour roadblock. Protesting against the city’s new, more modern buses, he’s asking for more transparency and support from the municipality: ‘We are being discriminated against, our roads are in terrible condition, the PumaKatari buses have better conditions than us,’ Aliaga says. These drivers are intent on continuing their protest until something is done. ‘If they don’t hear us, next time it will be 48 hours, and then 72 hours, until it’s an indefinite roadblock,’ Aliaga says.

Ultimately, protesting fills many functions. It can be practical: asking for a specific need. It can be political: The residents of Calle 21 of Calacoto asking for their street’s name to be changed to ‘21F No’ in a show of support for the 2016 referendum and in protest of the Constitutional Court’s decision (now residents in Cochabamba and El Alto are also asking for a similar change). But the protest is always social, creating a safe space for Bolivians to express themselves and uniting a group of people in a common fight. Bolivia’s political future may be uncertain, the country may be divided and people might be tired of the constant delays and inconveniences caused by roadblocks and strikes, but these are the expression of a democracy. They serve a very specific purpose and fill a vital role that allows the nation to breathe and react.

Photo: Alma Films

Marcos Loayza and the new voice of Bolivian cinema

The Bolivian film critic Pedro Susz wrote some years ago that filming in Bolivia is as difficult as building a Concorde airplane in a car garage. Despite the lack of demand for Bolivian cinema and the challenges met by the country’s film industry, in the last year there has been a rebirth in Bolivian movies. From Las Malcogidas, an acid musical comedy that tells the story of a woman of 30-something searching for her first orgasm, to Averno, released at the start of this year to tell the escapades of a shoeshine boy weaving through hysterical encounters within the underworld of La Paz. These are two movies that, despite high risks, have managed to captivate the Bolivian public.

But, one should keep in mind that tickets for Bolivian cinema remain significantly lower than their foreign competitors, perhaps revealing the importance of adventurous films such as Averno. Marcos Loayza, director of the film, parodically recreates the spaces and characters of the La Paz underworld to capture the essence of a place that resonates with Bolivians. Audacious in its narration, the story begins with a dream between life and death that merges into a plummeting trip down from the towering city of El Alto to a door in La Paz that leads to that mythological place, Averno.

Much like the spectator, Tupah, an 18-year-old shoeshine boy, does not recognise the moment he has left the real world. Running for his life through the indistinct, obscure city of La Paz, he encounters living ghosts; souls in pain, neither undead nor trying to return to their bodies.

Averno conveys similar stories the Bolivian grandmothers tell their grandchildren about the demons of deceased demonology, the Anchancho, a dreaded malignant spirit or the paths lead by Tata Santiago, a horse-riding truth guide. For the most part, it does not matter what these characters are called or in what scenarios or settings they appear. Loayza has gathered them all to immortalize them in the cinema; where funeral boleros coexist, where a saint who rides on a horse appears through a tunnel to save a life, and where drinkers in a bar walk on a floor flooded with beer in the name of Mother Nature.

Through integrating social realism with the fantastical, Loayza has pioneered a new platform of Bolivian cinema. His aim with Averno, is for people ‘to have more knowledge of the workings of a Bolivian film and the traditions and typical characters that are part the country,’ he says. Lucia Zalles, the marketing coordinator of the film admits ‘it is a risk’ to distribute the movie due to its exceptional and unusual nature. Shown in Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, La Paz and Tarija, the film has had over 17,000 sales by the third week. Although this on its own is a success, the question remains: Is this the right direction for Bolivian cinema?

In the last two decades, Bolivian cinema has been marked by transformations by outside factors. A considerable number of young Bolivian filmmakers received formal training abroad. Loayza however, has chosen to produce a distinctly Bolivian film set within the very city he was born. He devoted a lot of time to the production of the film, dedicated himself to the audio-visual world often left in the background, prioritising aesthetics and technique above narrative. ‘What I attempt to rescue is the dignity of having worked in the streets, having earned every penny honestly,’ he explains. ‘Choosing a shoeshine boy as the protagonist creates a very urban image ingrained in La Paz – they often hide their face and have a very definite, stand-out identity.’

‘The film looks to the darkest side of us as human beings [...] The cinema is a mirror for everyone in some way or another. I wanted to show another type of mirror, a distorted mirror,’ he says, pointing out that the film does not seek to judge but rather talks about reconciliation and forgiving oneself.

Averno has received predominantly positive reviews, with the majority of critics giving it five stars and agreeing that the photography, decors, costumes, makeup, visuals and screenography are extremely effective in creating Loayza’s vision of the creepy underworld. However, some viewers lamented the lack of script. Facebook user Pablo Rossel says ‘there is no continuity’ and calls it a story ‘without feet,’ while Kevin, also on Facebook, suggests it’s just ‘a film made of poorly made metaphors.’ Despite these few discerning comments, the reviews have mainly been positive with one English-speaking spectator even saying: ‘

is a movie that can take you to the underworld through a vivid journey to understand beliefs and locations intrinsically related to what life and death might be.’ This suggests that Averno has been vastly celebrated because it’s one of the few films to be typically ‘Bolivian’, revealing an unmet demand for quintessentially Bolivian movies for nationals and foreigners alike.

Much like making a film in Bolivia, entering Averno is not easy, but it is not difficult either, because you do not choose to go there. Averno is a limbo, a place where everything is possible and at the same time, nothing is. It takes us to the courtyards of memories and prompts the discovery of a magical story in the cinematographic voice of Loayza, which will perhaps be eternalised as a vital part of Bolivian cinema.

Photos: Iván Rodriguez Petkovic

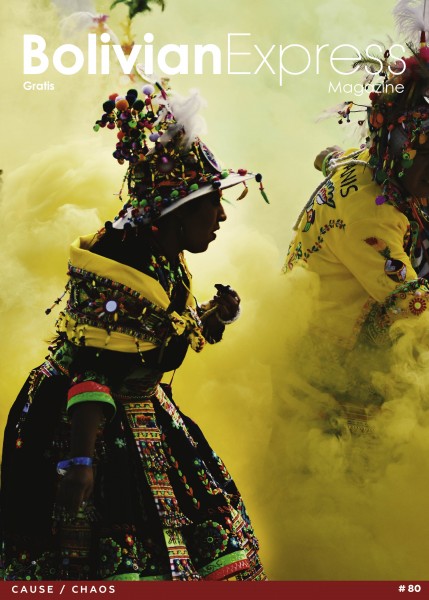

Innovation Keeps Local Culture, Customs and Costumes Alive

Vibrant colours, masks, sequins and feathers adorn the streets of La Paz during carnival and other traditional celebrations. La Paz, la ciudad maravilla, one of the New 7 Wonders Cities, brings together the work of hundreds of local people to make the carnival processions an unforgettable experience. The design and tailoring of Bolivian folkloric dress is the responsibility of artisan dressmakers, whose creativity and designs have the power to change people’s perceptions.

The English architect William John Thoms defined folklore as the traditions, poems, songs, catchphrases, tales, myths, music, beliefs, superstitions and other elements that characterise a culture. He coined this word from ‘folk’ (meaning people) and ‘lore’ (meaning wisdom and ability). Within this idea, he recognised folklore to be one of the purest forms of identity expression, with its ability to preserve and innovate a culture’s traditions.

The artisan costume makers of La Paz each have their own specialty; there are seamstresses, hatters, mask makers, tinsmiths and jewellers. They work in conjunction with one another to design and create hundreds of costumes for the country’s different folkloric dances. Carlos Morales Mamani, who has spent most of his life as an artisan dressmaker, works the entire year leading up to carnival designing new costumes and meeting the demands of the dancers. He is now the manager of a costume-design business that was founded by his parents, he being the only one of his siblings who chose to carry on the family business of artisan dressmaking. Morales creates his own designs and costumes based on the knowledge passed in to him by his parents.

In terms of style, the current range of costumes made by artisan paceños is more influenced by colonial fashion than by rural, indigenous style. Varina Oroz, an anthropologist and a curator at the National Museum of Ethnography and Folklore (MUSEF) in La Paz, says that many of the ‘local artisans’ sewing techniques are based on the embroidery of chasubles worn by saints and priests of the Catholic Church, and now they’re used to make folkloric costumes.’ But modernity is slowly creeping in, and the tradition of donning full traditional carnival apparel, including the use of batons, is no longer practised due to the large number of participants in the processions. Oroz says that fabric from France and Japan and Swarovski crystals were once used to fabricate carnival outfits. Today, though, clothiers use predesigned fabrics and strips of sequins in order to save time. Designs, too, have changed through the years, with baroque styles becoming more common and new shapes and symbols being incorporated, such as the dragons that appear on diablada masks (this was inspired, amazingly, by that creature’s figure on boxes of Hornimans tea!). Indeed, modernity informs new costume designs with the appearance of new characters, such as el Yapuri Galán in the kullawada dance, who is a representative of the LGBT community.

Carnival masks were originally made of plaster, making them very heavy, which was later replaced by tin. From the 1990s onward, tinsmiths and mask makers sourced their own raw material from discarded cans, which were then crafted with specialised tools. They were then nickel-plated to highlight a silver colour. Now, most carnival masks are made from glass fibre, a lightweight material that allows mask makers to fabricate even more extravagant pieces; some masks used in the diablada dance can even emit fire from the mouthpiece.

Photos and videos fail to capture the magnificence of these events; they cannot capture the excitement and energy of the exceptionally dressed dancers and the feel of music felt in spectators’ bones. But carnival occurs every year, and the municipal tourism agency La Paz Maravillosa invites you to experience this and other traditional Bolivian festivals in person, and perhaps in a costume of your own!

Download

Download