‘The artist’ emanates an exclusive aura. We kneel and revere, expecting him to exude a kind of spirituality, and ‘the artist’ responds by first cultivating the enigma and then finally getting lost behind a pretentiousness coat of paint. But today we are meeting someone who has not been lured down this path. Gabriel Barceló tells us he does not in fact consider himself an artist at all, he appreciates simple things and simple talents, like his ability to prepare a delicious Moroccan meal. We made a visit to find out more about this simple Spaniard, with a piece of La Paz in his heart, and Fez on his hearth.

BX: How is La Paz different from the other cities you’ve lived in?

GB: Well I come from Palma, in Mallorca... La Paz is possibly one of the most unique cities anyone could ever live in. It’s very different from Mallorca: there are lots of beaches there and we eat lots of fish, but here in Bolivia there are mountains, not beaches, and no sea at all. But this is why I like it: it’s helped me to get to know things I’m not used to. I like being in a city this unique.

BX: Do you consider yourself a Spanish photographer working in Bolivia?

GB: When I first arrived here, I would just photograph typical tourist things cholitas, their polleras, etc – or rather, I’d look at things with a tourist’s eye. But gradually – after two months or so – my vision started to change and these things became part of my daily life. I started to see these things not as touristy artefacts, but objects that represented something deeper and more universal. I see the people as human beings, and not as indigenous ‘others’; in terms of my gaze, I feel like a person from this country, although my techniques might be a little more foreign. I studied in Spain, after all. After three months here, the series of images I’d collected became a project.

BX: Tell us about your project.

GB: It’s quite personal. It’s called ‘Ajayu’, which is more or less the Aymara word for ‘soul’. Sometimes, you see someone’s face, a ‘lost’ expression, and you ask yourself: what’s the story behind that expression? It could be melancholy, hope, uncertainty – these are all states of the soul, universal emotions that I wanted to communicate through the expressions of others. This is the basis of the project, really. The important thing here is to avoid clichés, as these days traditional or folkloric themes are often viewed with the kind of eye that stereotypes. With Ajayu I’ve tried to look at these types of things with a contemporary eye, and I’ve tried to make them universal.

BX: How does the artistic process work for you?

GB: The most important part is your own gaze – what kind of things call your attention and how you interpret them – as well as what you want to say, above your technique, the way you photograph, I think. It’s also really important to leave the photographs ‘cold’ – that is, to give yourself time to separate yourself from what you’ve created so you can view it with a fresh eye, as if you were a third party. Then you can be truly critical.

BX: What does photography mean to you?

GB: Photography is a way of discovering yourself, that sleeping part of your being which focuses itself in your art. It’s like, you ‘re-read’ your photos after they’ve been developed and you see what you wanted, what was there subconsciously, before you took the photos. Above all, though, art is a verb. It’s about communication, actions, and emotions.

BX: Do you like llamas?

GB: Yes, I like them a lot. They seem quite strange to me... They pique my curiosity. They’re camels of the Bolivian desert, of the Bolivian altiplano. Photography is a way of discovering yourself, that sleeping part of your being which focuses itself in your art.

Tony Suarez. A name most people in La Paz know and associate with his eclectic photographic corpus. But did you know that this man had a life as eclectic as his pics? Born in Cochabamba, Tony moved to New York when he was twelve and lived there for about 30 years be- fore coming back to Bolivia. Despite having moved at such a young age, he confesses that he always felt like a migrant, ‘not really from there, neither from here’. After quitting Time, he decided to go back to Bolivia, a country he thought he knew too little about. When asked if he finally felt at home in Bolivia, he evasively answers: ‘I’ve been here for almost twenty years now and I’ve got my family and my networks. Moreover, I’m getting old and it would be harder to move and settle somewhere else. (...) Bolivia is a really amazing country, there’s so much to see.’

Tony’s chaotic career path first took shape during his time at university. He had enrolled for engineering, but quit after a year. These studies didn’t give him a ‘global vision of things’, it was much too restricted for his taste. He only really enjoyed English literature. After his mother gave him the choice to either go on with his engineering studies – which she would pay for – or to work, he went for the second option and began as a mail clerk at Time Life while also attending night classes. He tried a bit of everything before ending up in architecture, which he studied for about 18 months after which he finally found out what he really wanted to do with his life: photography. At that point he still had a part-time job at Time: he worked there in picture follow-up, developing and making safety co- pies of the flurries of the photographs converging upon their office from the whole world, before sending them on to Chicago. ‘I think it’s good to do other things than just what you studied to do. It gives you more possibilities and you learn a lot from it’, Tony adds.

After about a year working at the news center, he was appointed assistant photographer and later, photographer. All in all, his big adventure at Time lasted from 1968 till 1990 when he decided to quit because at that point it was becoming too restricted. The magazine didn’t give him enough opportunities anymore. Nowadays, he collaborates with various magazines such as Pie Izquierdo, Datos and Metro in La Paz, and In and Ve in Santa Cruz.

On a Monday afternoon, I went to his studio to interview him. He ushured me in his office, a small room crammed with hundreds of books and unusual objects – from a superman doll encased in its plastic box, to sinister masks and wooden crosses on the walls, dispersed among photos and paintings.

BX: Are there places, events or experiences you particularly remember?

TS: There are so many! I had the opportunity to attend the first spacial launches, five Olympics games, football cups, I travelled so much... and I enjoyed it all. Even though sometimes, I did so many different things, went to so many different places and everything was going so fast I didn’t really have time to sort of digest it all.

BX: So it was like an overdose of images and experiences...?

TS: No, I enjoyed as much as I could. It felt so good to experience so many things and have the feeling I was totally free. I remember once being on a bus abroad and thinking ‘I am so free that if I died tomorrow, it wouldn’t matter’. I love the variety and discovering new things. In this aspect, Bolivia has a lot to offer, since you have so many different things in just one country and you don’t have to go far to see a quite different type of landscape.

BX: Do you dedicate yourself to a specific kind of photographs - portraits, landscapes...?

TS: In Bolivia, the market is so small that you have to do a bit of every- thing. Otherwise, it’s not possible to live from it.

BX: Do you work more with Black & White or colour pictures?

TS: Black & white and colour pictures are two different ways of thinking but they’re both really interesting. I used to work a lot in Black & White but it’s better to work in colours for the archive. When you archive pictures, it’s always better to have them in colour. And then, you can do whatever you want with them, you can edit them and turn them Black & White. On the other hand, the process to develop B/W pictures is more complicated and it’s harder to get good B/W pics. For example, in books, it’s much easier to print a good colour picture than a B/W. The colour also helps a lot, it catches the eye before the spectator pays attention to the composition. While with B/W, if the composition is not good enough, there’s nothing appealing to the picture.

>BX: What do you think about digital photography? Do you prefer film cameras? Do you use editing pro- grams such as Photoshop?

TS: Photoshop is a program which integrates really well the logic of the photolab. Nowadays, I work with a digital camera because here, it’s not possible to find the chemicals to develop the pictures and consequently, there are no lab to develop them. It’s hard to import chemicals because of drug import issues. But both ways of taking pictures have their charms and advantages.

Digital photography is more accessible and quicker while film photography is a bit magic: you see the image re- veal on the paper, spring to life. But it’s also an art; many photographers do not have the technique to develop the pictures themselves so they have to work with someone who does in the lab. In this case, they have to each know what they want in order to collaborate and get good results. I’ve always developed my pictures myself because I had the opportunity to use a lab from the beginning: when I was studying, I also worked at Time, where I could use a professional lab for free and I also frequented people who gave me advice. I learnt a lot from it.

As for Photoshop, I don’t know enough to do more than just editing my pictures, i.e. correct the brightness, contrast... I don’t have the skills to really ‘create’ a picture with such programs. But I believe that it is a great thing to have to opportunity to do it. However, when you use such a tool, you have to mention that you’ve used it, that the picture has been modified; maybe I’m old-school, but you have to keep some professional ethics. You cannot use Photoshop in journalism, to modify the content of a picture. As for the artistic point of view, a photoshopped picture can be as good as an instant pic. But you have to differentiate the documentary value and the plastic/ aesthetic value of a shot.

BX: Do you have some specific projects in the near future?

TS: To work on a book. The truth is that I did many things and I haven’t had time to just go back to them. So I’d like to see what I’ve done and then, see what could be done out of it, try to bring out a main theme. But a book is something which has its own life. It starts developing it’s own character as soon as you start writing. Even if you have ideas in the beginning, it doesn’t always end up the way you thought it would.

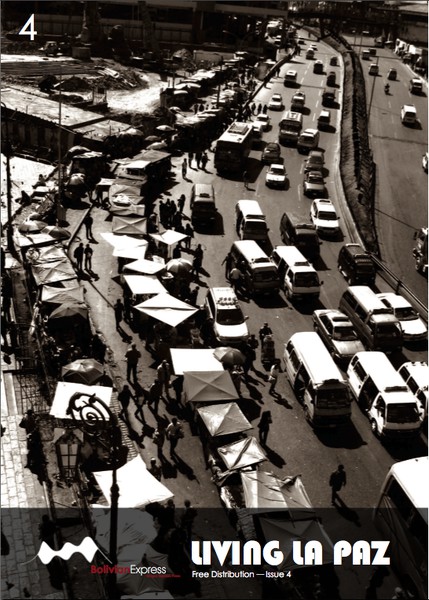

As has been discussed in previous Bolivian Express issues, the city of La Paz is not short on artistic creativity and expression. This can be witnessed first hand all over the city: every spare bit of wall, building or lamp post has been decorated. We see murals, street art, advertisements selling absolutely anything, and even banners and posters spreading political ideas.

As Bolivia’s capital, La Paz is the central hub of the country’s commerce, and this is evident in the clamour for advertising space on every available inch of the hectic streets. However, perhaps the most interesting and unusual form of advertising (from my European perspective) is the almost photographic paintings, used to advertise anything from bottled water to an electronics business.

As a European, I notice and appreciate the street art advertisements for their unique artistic value above their obvious marketing purpose. For me they provide a refreshing change from the huge billboards that jump out at me when cruising the motorway.

Do Bolivians however, feel the same way? We asked some random passers by, who were surprised that we had even given it thought.

Hector from El Alto said: I have always liked the painted advertisements more than big plastic posters or things like this, as they are more natural, and it is much cheaper for businesses to advertise in this way.

This view was echoed throughout the half a dozen people who we spoke to and generally it seemed that most people were now so used to advertising in this format that they were simply surprised we were drawing any attention to it at all.

One of the most striking characteristics of the works we find are their detail and intricacy. „Graffiti“ in Eu- rope is generally less respected and usually less meaningful, (with a few marked exceptions like Britain’s rebel ""Banksy"", a lauded Graffiti artist). The grandest of Bolivian mural we have come across sits along ‘El Prado’. In Europe this type of ‘art’ is more usually described as vanda- lism (which is why Britain’s „Banksy“ remains staunchly anonymous) but once again this could not be further from the outlook of most Bolivians. Ana said: ‘The street art is fantastic; it brightens up our streets and covers over some of the dirt anyway. The artists who do them are very well respected and for me they add to the beauty of La Paz. However, I think that it is always best when people ask for permission to do the murals, this is always better than art that just comes from nowhere, I still like them though!’ Finally, and perhaps the most interesting form of street art, found not only in La Paz but all over Bolivia, are the political messages shouting for votes. Usually the principle aim of the propaganda posters is to reassure people of the current government.

Classic messages such as “MAS” or “Desarrollo” or “Todo va a cambiar”, line the main traffic thoroughfares. For a European this is again a fairly alien concept. In that far off continent the vast majority of political advertising only surfaces around election time. Parties try to keep themselves out of the firing line as much as possible in a meantime. In contrast, a painting here can stay on the wall for up to 20 years. We were obviously curious as to what the Bolivian people think of these political propaganda paintings and posters, and wanted to see if they actually had any effect of the public psyche. As with all things like this, opinion was hugely divided, and this, it appears, is a reflection of the general political situation in Bolivia: “The paintings are everywhere you go so I almost never notice them anymore. Of course you see the blue paint of ‘la MAS’, but I guess to me it does not have an effect, as you see so many paintings. Maybe it has something to do with which way I vote as well.”

Keen to voice their opinions, some people were more than happy to go into depth about the Morales government:

“Evo Morales has done so much for the Bolivian people and I believe he will do a lot more in the future uniting the nation. With the blue paintings I think it is important to get the political message out to the people, as for the paintings themselves, I always notice them”.

Evo Morales has been the great hope for the poorer sections of Bolivian society since his election in 2006 when he won the presidency with a 60% majority, and became the first indigenous president. However, as Alistair Smout’s article (Bolivian Express, August issue) has commented on, not all of Bolivia is united behind some of the policies that have been introduced. The propaganda is intended to reassure those doubtful followers that the current government is fulfilling its promises. The ‘masista’ group called ‘Los Satucos’ are the group responsible for the blue ‘MAS’ propaganda around the city and one reoccurring theme is the face of el ‘Che’ Guevara, the revolutionary best known for his work in Cuba. His face recognisable all over Latin America, associated with revolution and change, and is thus the implicit message pumped to the Bolivian population through street art. Whilst the methods are different in Bolivia to those I am used to in Europe, there is no doubt that similar things do occur, simply in a different format and volume. The streets of La Paz are consequently a thriving space of activity, where no space remains silent for long. If all those painted faces could speak, it would no doubt drown out even the traffic of La Paz, and that is an achievement.

Download

Download