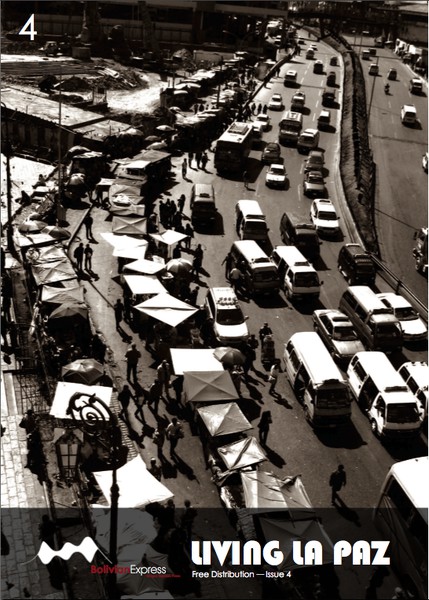

When arriving in La Paz the general chaos everywhere is one of the first things you notice. The city of La Paz is a pioneer for a traffic safety project. For the tourist new to Bolivia, the trafic is possibly the first cultural shock: the disarray of the traffic can look like a complete maze of confusion with- out rules or guidelines, but it is in fact a little more complicated than that. As a spectator it is hard to see how the traffic can flow smoothly without traffic collisions and whilst they do occur they are nowhere near as common as one would expect. The traffic, and drivers seem to govern them- selves despite the best attempts of the whistling police officers no government laws or regulations seem to have any impact on the way people drive. Whilst law 3988 does exist in attempt to control drivers and regulate the traffic it does not appear to have much affect on drivers jumping red lights or blocking intersections. All the noise and chaos of the traffic, and the police whistling, as well as the con stant drone coming from minibuses of ‘Prado, Perez, San Francicsco, un boliviano!’ make up the La Paz urban and ‘acoustic’ landscape.

We went out in the streets of La Paz to learn more about what the people actually think of the traffic:

‘The traffic is complicated here, it is a big mess and there is no respect among the motorists. I think one of the reasons is that the drivers have no education in driving. The chaos may also be a consequence of the disorganisation. Every bus or trufi is doing the same, driving in the same directions in the same roads. We need clear lines with different destinations to organise the traffic.’

The hectic traffic flow is fascinating in the way it can dominate the city. As there are no official bus stops, and there are so many ways to get from A to B, waiting at the side of street every passing vehicle competes for your custom. There seem to be far too many Radio taxis for the number of people who actually use private transport, and to increase the numbers of taxis on the street still people walk around selling black and yellow taxi signs so that unoffical taxi drivers now also run the streets. The old U.S. style school buses defy the laws of physics as they struggle up and down hills through the narrow streets. They comfortably fit approximately 30 people in, but this roughly translates to if you can breathe then hop on! Probably the most popular and common form of public transport in La Paz are the minibuses. They run to all corners of the city and will stop anywhere for just about anyone. The minibuses are distinguishable by their colourful signs with their next stops in the windscreens. In theory therefore, all very easy and straightforward. Each minibus is run by a driver and co-driver, or voceador. The voceador’s primary objective is to drum up business for the bus, calling out endless names of places in the hope that eventually a passer by will be tempted. Their task then is to somehow get 1 Boliviano off every person, and hop on and off every couple of minutes making way for new passengers. The voceador can take the form of anyone, from fully adorned elderly cholitas to a young boy of eight years old!

An ice cream man explained the role of the voceadores to us:

‘The voceadores are shouting out the destination and also the prices for the trips to get attention. That is because of the competition between all the buses – they need to attract passengers and to announce themselves so people will get on their bus.’

The general approach towards traffic lights is that they are a guide. At peak times, in places like Plaza del Estudiante the traffic lights have been abandoned all together in favour of officious police with whistles. Another government measure brought to control the mayhem are the unique Zebra traffic wardens, which apart from bringing a smile to your face, form human Zebra crossings as they stop oncoming traffic. These ‘zebra wardens’ encourage drivers and pedestrians to respect, or at least acknowledge the laws and they are particularly beneficial for young children. These cebras are of- ten students between the ages of 16 and 23 who, as well as studying spend 4 hours a day working with the traffic. Across the city there are around 120 cebras working every day. As well as their work on the streets, the cebras also go into schools, teaching future drivers the rules of the road, dressed of course in their ‘paso de cebra out- fits’! The outfits are basically a reflection of the paso de cebra, or zebra crossings colour scheme, and are thus the black and white suits that are around the whole city.

We managed to catch a couple of stray cebras in one of the most chaotic traffic spots in La Paz, plaza San Francisco:

‘The job can sometimes be hard, and a lot of people have no gratitude or respect for our work, and still drive the way they drive, but at least it is warm in the outfit!’

‘It can be rewarding and fun, and we try to be as happy as possible jumping around waving our stop, go signs about. We helps kids the most, and try to have as much fun with people as we can.’

Organising the La Paz traffic is one of the Gobierno Autónomo Munici- pal’s primary objectives. The idea is to connect the city of La Paz with different bus lines and public buses to cut down on the sheer volume of traffic, and also to some extent control it. People have generally adapted to the traffic situation in La Paz, and whilst paceños aren’t necessarily entirely happy with the chaos they appear to tolerate it!

As a date with Bolivia’s number one swimmer, Hector Andres Viscarra Bustillo, loomed, I naturally tried everything I could to find out as much as possible about him. Unfortunately ‘Google’ couldn’t come up with the goods, and neither could ‘Wikipedia’; in fact online there was next to nothing about Bolivian swimming, or even swimming in Latin America whatsoever. Thinking this was slightly strange for one of South America’s top swimmers, I was starting to get rather sceptical about the man that I had been reliably informed was ‘one of Bolivia’s best’.

Like many other people in the UK, swimming only really appears on my radar once every four years, since for the first few days of the wall-to-wall Olympic coverage, swimming seems to be just about the only sport the Brits excel in, and thus gets ample BBC footage. Consequently, these four to five days are pretty much where my knowledge of swimming starts and ends, so in an attempt to sound clued-up to Bolivia’s most famous water dweller, I called upon a very reliable source from back home to give me the low down on the world of swimming. Hector’s mother drove us to the impressive facility and sports complex in the ‘Zona Sur’, La Paz’s richest suburb, and with Hector crammed in the boot she proudly showed us some of the silverware he had amassed in his young career. A considerable highlight was a wooden paddle which he had been given recently for winning a race on Lake Titicaca. As if to prove that swimming was more than just a very efficient way of not drowning, Hector changed and had a splash around in the pool, posing for some photos in the front crawl position with proficiency and panache befitting one of South America’s finest. He eventually settled into position on the side of the pool, and the interrogation began.

Unfortunately, what soon became clear was that the avid research I had conducted beforehand would be completely useless; as it turns out he is in fact an ‘open water’ swimmer, meaning that all the complex swim suit technology engineered to take milliseconds off times didn’t apply to him at all, and all the research I had conducted about altitude training in the pool was completely redundant. Undeterred, I pressed him on what it was like to be a swimmer in Bolivia, whether anybody knew who he was, or whether the press or media ever took any notice of what he was up to. He laughed this one off, simply saying ‘I’m not a footballer!’ In Bolivia it seems that to gain any kind of sporting fame you have to be a footballer, simply because it is the only sport which has regular television cover- age and mass appeal. The same can be said in Europe, as football tends to be the only the sport which has year round media coverage, and thus the biggest most famous faces. But did he begrudge the media attention and wealth that footballers command? De- spite the fact that he is arguably more successful, no Bolivian football player could lay claim to being the third best on the continent! ‘No, football is very competitive and difficult to become an important player, and also it is much easier to train and study when the media are not calling you for information.’

This level headed and reasoned approach revealed that at the same time as being a near enough full time athlete, he is also studying a gruelling engineering degree. He went on to explain the difficulty in balancing the student lifestyle with being an elite sportsman. Going out with his friends was cited as the main sacrifice, since with early morning training sessions and regular competitions it was vital not to waste all the good work he has been putting in. So surely when you compete and train you have to miss classes from time to time? His response was that in reality studies come first, and along with his Cuban coach Orlando Valdez, they build his schedule around his studies and his examination periods. His basic schedule revolved around eating a lot and training around 2000-4000 metres per day in the pool. But surely this is completely different from your competitions? Answer: ‘yes!’ However, clearly the main difference is the water temperatures involved. During a race on Lake Titicaca a few weeks ago Hector swam in temperatures of 7°C, whereas the normal temperatures for competitors in Europe and elsewhere in the world are from 16-17°C. To combat these temperatures you have ‘to swim very fast!’ and also on a more practical level, lather your body up with Vaseline and a menthol solution, as well as again taking on vast amounts of food to keep the fat content up in your body.

Astonished at how he could possibly function in these water temperatures without cramping I felt inexplicably compelled to tell him about my problems with my feet cramping every time I went swimming…Needless to say this was not a problem he had ever experienced, but still seemed to have some sympathy for my curtailed career.

Knowing very little about open water swimming I wanted to find out more about the races themselves, so asked him whether there was much in the way of ‘tactics’ in the water, in other words ‘fighting’. His eyes lit up as he then went into great detail about how ‘holding your space’ at the beginning was one of the most important parts of the race. ‘There are judges but it is extremely difficult for them to see what happens under the water, so kicking someone who is just behind you can be made to look very accidental. To be honest the advice of my coach is to get ahead early and then get away from the pack, and then it is more about the swimming.’ And it appears this tactic has brought him much success, judging not only by the weight of his medals basket, but also by the news that he has recently become the Bolivian record holder at 10km, swimming in a time of 1 hour 22 minutes in Tarija. Whilst this is nearly half an hour off the world times of the top athletes from Europe and the U.S.A. a Bolivian record is a Bolivian record, and when you consider that he is essentially part time athlete, this is an impressive feat. I then quizzed him on the impact of the altitude on his times and also, crucially, on his com- petition, as people from the low lands come to compete in places like Tarija.

He was keen to play down the impact of the altitude, saying that the water made for a slight altitude leveller, as for the science in this theory neither I nor he was sure, but he felt that he was at little to no advantage when competing in coastal races.

We finished our discussion with his even- tual goals and ambitions in swimming. Next up are the Pan-American Games in Guadalajara, Mexico, which he hopes to qualify for. He does not hold high hopes for the London Olympics in 2012, as they are both a long way in the future, and daunting qualifying times loom. He then went on to describe how ultimately his studies in engineering, and getting a good job as a result of this degree would be what secures his financial security in the long run, not the swimming. It seems that this is the reality of most sports in Bolivia, unless you are a footballer it seems there always has to be a back up. In the fortunate case of Hector Andres Viscarra Bustillo, he has the chance to live the dream, before settling on a prestigious career as an engineer. At the same time as being a near enough full time athlete, he is also studying a gruelling engineering degree. Along with his coach, they build his schedule around his studies and his examination periods.

Something that may slap you in the face when you arrive in La Paz is the seemingly impossible combination of western modernity and its various local antidotes. In a society where half the people retain many of their Aymara customs, and where most people still partake in pre-Columbine rituals, there is scant room for deviance from these powerful influences - both ancestral and contemporary. Moreover, due to a strong Catholic influence in the city’s social and moral fabric, locals often exhibit a marked conservatism in their behaviour and tendencies, despite the seeming exuberance of traditional festivities (such as the entradas and carnival). One notable transgression can be found in ‘los Metaleros’.

Metal arrived to La Paz in the early 80s, a likely product of the rebelliousness brought about by the demise of oppressive military dictatorships. Paceños were likely drawn to it through the violently powerful volume of its music, as well as by the cataclysmic spirit of destruction it brought with it. Besides, back in the day when black was the new black, it was important to be seen to be doing your thing for fashion. Perhaps even a hint of Latin American tough machismo needs to be summoned to explain the rise of this movement. The most influential bands of this decade were ‘Sacrilegio’ and ‘Track’ which proved to be icons for ‘Metaleros’ in La Paz at the time.

In an attempt to get closer to metal in La Paz we wanted to go to a live concert. One dark and lugubrious Friday evening we made our way to ‘La Gri-feria’ only to find, rather disappointingly, a completely empty bar. The owner explained that the municipality made him cancel all the gigs until November due to complaints from the party- pooping neighbours. The fatality of this venue meant that ‘La Oveja Negra’ (in El Alto) is probably the only true Metal pub still open with regular performances. Disappointed not to see a live metal concert, we contacted the local metal band ‘Undead’ for an interview. Founded in 2000, they’ve recently re- leased a ten-track album ‘Beyond the Soul’, and even played a few songs for us during the interview.

BX: What kind of metal do you play?

UD: There are many kinds of metal: heavy metal is the root but there are many other sub-genres. We play Dead Metal and Melodic Dead Metal and one of the main features of this style beyond the aggressive guitars is the guttural vocals.

BX: How did you decide to create the band?

Jaime: Marcelo and I met when we were young and we had the idea of forming a band. At the beginning, it was just us, and Marcelo didn’t even have a drum so he played with a key- board and assigned a different beat to each key. People kept on asking him if he played the keyboard in the band and he would say ‘No, I’m the drummer!’

After one of our first performances, at “La Kalaka”, in 2001, we disbanded for a while: we had discussed which songs to play beforehand but on the night Marcelo was so nervous he kept on playing the wrong ones. After the third ‘erroneous’ song, I lost it and we fought in front of the whole audience! After that we decided it was time to split. In 2007 we got together again and found three guys who wanted to play with us. We then played at “Sur Metal Fest” and shortly afterwards we lost our guitar player, and met Boris who’s been in the band ever since.

BX: What do you think about the status of metal in Bolivia?

UD: It’s growing. A few years ago, you always met the same people at metal gigs but nowadays, there are more and more people who like metal. How- ever, it’s still mostly an underground scene and still logistically difficult to organise. For example at the ‘Illimani Metal’ concert the organiser had to fill in loads of forms for just a 5 hour set, but if a ‘Cumbia’ or ‘Reggaetton’ group performs, it’s considered less of a problem. Bolivian society is still not open to metal but I believe that it’s the only kind of music which goes beyond time. I mean, if today people listen to Hanna Montana, tomorrow they’ll listen to if 15 years ago you listened to ‘AC/DC’ or ‘Sepultura’ in 20 years time people will still appreciate the music.

BX: So how did you each start in Metal?

Marcelo: I began playing the key- board and the bass and then I fell in love with the drums when I was 14. The first song I played on the drums was ‘Mutilación’. But as Jaime said, I began ‘drumming’ with a keyboard. I bought my first drum kit 8 years ago for $500 and I’m still playing it.

Jaime: At the age of 6 I was interested in the saxophone but then saw my first metal video and knew I wanted to be a rocker with long hair! The first song I played on the guitar was Nirvana’s ‘Come as you are’. My parents weren’t keen on me playing the guitar so, at 13, I began saving money: I used to pretend I was going out so they would give me money and I spent the whole evening sitting on a bench until it was late enough to go back home. After a few months, I’d saved $80. I asked my father to take me to the guitar shop and after he saw $80 was just enough to buy the cheapest guitar, he gave in and bought me a $280 Washburn. To begin with we played at friends’ parties, then friends’ of friends, and we progressed. In the end, my parents accepted it but I still studied because my real passion is music.

Boris: My family has always been really into music, so I began studying it when I was 8. At the beginning I was a pianist, a real one not a fake one, and I have used many keyboards in my life! My first band was ‘Nordic Wolves.’ Now I play the guitar with these guys and I feel very comfortable playing with them because they are very spontaneous and we completely understand each other.

BX: What does metal mean to you?

UD: Our lives are based on metal, of course we have to have something else beyond music, but the main thing in our everyday life is music, so sooner or later we hope to be able to make a living from it but we know that here in Bolivia it is nearly impossible so we have our professions for financial stability.

BX: One controversy surrounding metal is ‘Mosh’, can you explain it?

UD: ‘Mosh’ is the most elemental expression of ‘Metalero’ feeling, it is basically having fun listening to the music but it can get pretty aggressive and the ‘moshing’ depends on the type of band and music.

BX: You sing in English. Do you worry that people won’t understand?

UD: It’s easier to write and sing in English. In Spanish, it’s more difficult to find the right words and the lyrics are always secondary anyway, and it is more about the sound, so no!

BX: Is music a way of life in Bolivia?

UD: Music here is always just going to be a hobby. Money is the biggest problem for Bolivian artists and unforntunately musicians will always need a back up income until they go ‘inter- national’.

The Undead:- Diego Machicao (30) Vocals and Anthropologist

- Marcelo Escobar (29) Drummer and Psychologist

- Jaime Zambrana (29) Lead Guitar and a Systems Engineer

- Boris Algarañas (30) Second Guitar and Industrial Engineer

- Mario Castro (30) Bass guitar and Psychologist

Contact information: http://www.myspace.com/undeadbolivia

Online links: http://www.animaprod.blogspot.com http://www.myspace.com/animaband3

Download

Download