It seems, then, that the face of hip-hop – at least in Bolivia – is changing. To investigate this a little further, a few of us took a trip to an incredibly obscure-sounding ‘experimental hip-hop’ dance workshop in the Zona Sur. In a word: what?

As it happens, experimental hip- hop is just taking off in Bolivia (but apparently not the rest of the world). We weren’t there to actually take part in the workshop; instead, we had come to inter- view the choreographer of ‘The Marionette Show,’ a new dance extravaganza that combines hip-hop with various other styles (hence ‘experimental’ hip-hop). “‘The Marionette Show’ was originally performed by dance group Expression in South Korea in 2006,” Marco Olaechea explains, “but we’ve shaken things up a little bit. We’ve added a new style based on hip-hop and geometrical shapes, with a bit of tap dance and waving.”

So what’s ‘The Marionette Show’ about? Well, as Marco tells us, the main message is that no matter how old you are, you have to hold onto your imagination. Seems like a strange message to communicate through hip-hop. “Hip-hop is an attractive, universal language, so there are plenty of people who want to get involved,” says Marco, and looking at the people who’ve turned up to the work- shop, that sounds about right. “For me, hip-hop has always been a way to express love, to create art through love. It doesn’t have any- thing to do with the violence and aggression it’s often associated with.”

“A lot of thought has gone into the show: it’s been in my mind since at least last September,” Marco continues. “Actually, seven years ago I came top of a reality show dance competition, and got to stay in Chile for four months. There I met Vanessa – who helped to organise this show – and it’s been our dream to share the stage ever since.” Sadly we were unable to interview any Chileans as they were all suffering from an unfortunate bout of altitude sickness during rehearsals, but Marco assures us that there are plenty more of them – including principal dancers Claudio and Leticia. Speaking to Marco, it’s clear that he and the rest of the team are very dedicated – for one, Marco funded the production almost entirely by himself – but how does ‘The Marionette Show’ hype match up to the performance on stage?

After trailing through wind and rain to the Zona Sur, discovering that the same tickets we had booked had also been sold to another group, and relocating to the illustrious row Q (right in the back-left corner of the theatre, in case you were wondering), we were finally ready to see the spectacle La Paz had made it so difficult for us to enjoy. And we were pleasantly surprised: the show was essentially a remixed version of the film Amélie, and by ‘remixed’, we mean re- placing all the characters and the story with a bunch of scantily-clad breakdancers backed by a Yann Tiersen soundtrack trying to find a girl who is, coincidentally, named ‘Amélie’. The quality of the dancing, children and adults alike, was impressive, particularly a scene featuring dancers suspended from pieces of cloth. Through ‘The Maronette Show’, we finally learnt the true meaning of experimental hip-hop (maybe someday you will, too). We can only hope that the show’s six-year-old star – who has been practising yoga since she was three and wants to be a dolphin when she grows up – appears on stage sooner rather than later (I don’t know about you, but I’d be interested in seeing a dolphin attempt experimental hip-hop. Give it a few years).

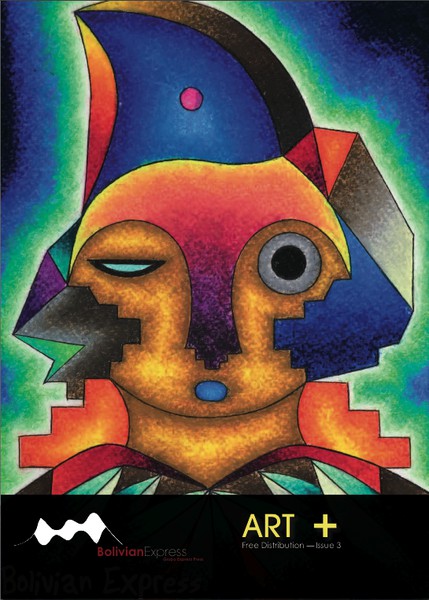

Waiting ages for an interviewee to turn up for the second (yes, second) time isn’t exactly my idea of fun, but when said interviewee one of the most famous artists to come out of Bolivia, I’d happily while away my hours admiring alpaca jumpers and investigating Machu Picchu tours on the Sagarnaga until he arrives. The work of Mamani Mamani – who goes by the name of ‘Roberto’ (or ‘Robertito’) to his nearest and dearest – is instantly recognisable. Waiting outside a shop of his, filled as it is with Mamani-brand paintings, mugs, postcards, and the like, I can see why. It’s the colours: similar to the Andean flag, barely a single one goes unused. But what to expect from such an artist? One of those eccentric, new-age types, with garish clothes to match his personality? The beret-wearing, drum-tapping, turtleneck-sporting variety of artist, maybe?

The man who eventually greets me isn’t exactly what I expected (granted, my expectations were allowed plenty of freedom given the time I was left waiting). For starters, he’s rather small. His voice is soft and quiet, and he sits with his hands clasped in front of him on the table; every aspect of his appearance, his body language, sug- gests someone distant but gentle. In a nutshell, he gives the impression of someone humble and serious; the look on his face gives me the impression he knows some very profound, important secret. Here’s what we got to talking about.

BX: To begin with, have you ever actually studied art?

MM: No; I studied agronomy and law. I think of art as a vocation rather than a profession. I’ve always had this artistic being inside of me; my first drawings were with charcoal my mother provided me with, and since I was very young I’ve been painting on whatever I could get my hands on - be it newspapers or bits of card. When I was fifteen I won my first competition, and at eighteen I won the Premio Pedro Domingo Murillo – a very important prize in Bolivia which opens a lot of doors.

BX: Would you define yourself as self- taught, then?

MM: I don’t really like that word. Every- thing I needed was already inside my head, a part of my being, inherited from my parents and their parents. I didn’t ‘teach’ myself anything.

BX: Do you admire many Bolivian artists? If so, which ones?

MM: Antonio Mariaca immediately springs to mind; I’ve always had his work in front of me. Gil Imaná is another influence, and Fernando Montes too – I stayed with him in England. I shared the Pedro Domingo Murillo Prize with Oswaldo Guayasamín, an indigenista artist I admire; I’ve also had the fortune to meet and talk with Victor Delfín, a Peruvian artist. My true masters, I think, are the ceramistas of Tihuanaco, the tejedores of Nazca, all the artists of Pre-Columbian culture. These influences provide an interminable source of inspiration for me.

BX: How would you define your artistic trajectory?

MM: My art comes from the Aymara world, so it shares the same ideologies – harmony with nature is certainly very important. My art comes from my heritage, from what my fathers and grandfathers thought, believed, and experienced. I’ve spent a lot of time outside of Bolivia and Latin America, though; I’ve spent year each in Japan, France, and Germany, and travelled around exhibiting my work. All of these things have nourished my work. For me, though, the departure point is the most important, and so I’ve returned here, to my homeland, to my roots. My art is like a table pre- senting offerings to the Pachamama, the sweet offerings of colour. My art is a thank-you to this land, to these mountains, and to these gods.

BX: You mentioned ideological battles (‘luchas ideológicas’). Can your art be linked with any particular political or cultural ideals, then?

MM: Not strictly. My art is linked more to culture, the deep roots of ancestry, of pride, of identity, of this magnificent culture we all inherit. My work doesn’t subscribe to a political ideology or party.

BX: In a nutshell, how would you de- scribe contemporary Bolivian art?

MM: There are movements, but ultimately every artist works in his own space. We all have our own things to say and our own ways of saying them. You’ve got to remember that Bolivia is culturally very diverse: it’s made up of more than forty different nations, each with its own codes and symbols. Here, art sprouts from the skin; there’s no need to subscribe to movements, really.

BX: Do you think contemporary art in Bolivia is accessible, or is it something that can only be appreciated by a cultural/social/intellectual élite?

MM: Art has always seemed to attract an élite, because that’s how the mar- ket works. I’m trying with my work to ‘socialise’ art a little bit to break this artistic trend, and I think it’s working. I’ve designed cholita shawls, post- cards, calendars, and the like (which has attracted some criticism). But if a person can’t buy a picture for five million dollars, why can’t they buy a postcard for five bolivianos? I want my art to be for everyone. It’s one of my main preoccupations.

BX: Would you consider commercialism a problem with Bolivian art today?

MM: A good work is good wherever it is in the world. If it’s good, people will pay for the work. I think it’s the challenge of the artist to transcend the commercial aspect of art. If someone makes a work of art just to sell it, they don’t have much life in them, and it’s life that sells.

BX: What’s your favourite colour?

MM: I’m a colourist, I work with colours. Someone once said: Mamani Mamani put colour into the Andes. For me, colour is life. Strong colours combat bad spirits; they help us through the darkness. Each colour has its strength. But the colour that always features in my work is yellow... For me it represents energy, the aura of beings. It’s the colour of strength.

BX: What’s your favourite film?

MM: Yesterday I saw a Turkish film. That could be my favourite. It was about a modern, fatalistic love, and it had good music. I like those European films that aren’t commercial. They can feed your soul.

BX: Morenada or Caporales?

MM: Morenada. It’s a manifestation of the community, and it’s more intimate, more about blood and skin. The evening after the interview, I go to an exhibition of Mamani Mamani’s; if it were an album, it would be his ‘greatest hits’. The venue – Café Campanario, just off the Sagarnaga – is sleek and shiny, with canapés and glasses of wine on offer, and the people there match it. It seems that any viewing in the Café Campanario isn’t going to be for the masses and, whether he likes it or not, Mamani Mamani has become something of a cult figure amongst the Bolivian middle-class – it is art, after all. Little by little, though, it feels like he’s winning the battle against an elitist conception of art.

Deep South, also known as Ricardo Prudencio, is a well- known DJ harbouring an obsession for Andean Trance music. Bolivian Express journalist William Barnes-Graham caught up with him in July to quiz another artista paceño about his musical experiences in Bolivia and beyond.

BX: Firstly, is there a club night that you DJ at or go to regularly?

DS: Not really... there are several night clubs in La Paz, but none of them are my style. Traffic, in the Avenida Arce, is the best one, I think. I DJed in Cuzco last week, and in a couple of weeks I’m Djing at a big Andean Trance festival on the Isla del Sol in Lake Titicaca. Lots of international DJs are coming!

BX: Sounds fantastic! So how did you get into trance?

DS: I started when I was 17 years old. I went to Cancun on vacation, and visited an electronic club. That night my life found its purpose: I said, “I should be a DJ!” Since the very first beat I heard I knew that trance was for me and straight away I contacted Erofex and Reika, DJs in the electronic scene, and they introduced me to the party scene. Since 2004 I’ve been a part of Neurotrace. It’s a collective that organises parties, both indoors and outdoors. I have a book with all the flyers of parties I’ve played in it, and since 2004 I’ve collected more than 100 different flyers.

BX: Wow. To have been doing it for so long with such success would suggest that there is a bit of a trance scene in Bolivia; is this so?

DS: Well, the scene is small but strong. There are other trance DJs here, mostly in La Paz, which is the capital of trance. In Cochabamba and Santa Cruz the scene is mostly house music, techno, or minimal. You also get a lot of foreigners in La Paz, who are massive fans of the trance parties we hold, and the paceños themselves are big fans too.

BX: That’s not surprising since trance has remained strong in Europe. So, if I wanted to go to a good trance night, where would you recommend?

DS: There are a few trance nights at Traffic, mostly pro- gressive stuff. On Thursdays you can find progressive trance in La Luna bar. Every couple of weeks we hold a big party a little outside of the city, indoors or outdoors, because there’s a law that lets us go on until after sunrise! In the city you can’t legally party later than 4am. It’s like a festival – you can camp with a few friends, party, and then come back to the city.

BX: Awesome, will look out for that while I’m here. Do you have a particular type of trance that you play or listen to?

DS: My style’s psychedelic trance, but I love to listen to all styles of electronic music – chill out, drum & bass, down tempo, progressive, minimal... All styles have their good music, and I believe that there’s one perfect song for each hour and place and moment.

BX: Do you have a perfect song that you always like to listen to or play?

DS: Yes – I have my favourite artists, and all of these artists make music that invoke different feelings. It’s very sentimental music – it can make you cry on the dancefloor! – but it’s a soul-cleansing experience. You know that a dj is like a shaman of the new generation?

BX: It certainly seems like that when I’m listening to a good one.

DS: When everyone is dancing to the same beat, with this music, you usually dance alone, and everything disappears for that moment, all your concerns, all your worries, all your problems... I love that moment, I live for that moment. Of course, many people think that electronic music is for drugs, but I hate when that environment turns beautiful dancing into shit. There’s no drug like the drug of music one might say. Hell yeah!! BX: Do you feel that drugs in clubs are a big problem? DS: You can always count on the music to take you out of this world. I’m part of a group that’s organising a big music festival in La Paz in October called Samhain festival. It’s going to be 3 days, in a castle in the jungle of La Paz. Here we’re trying to change people’s point of view of partying. We have lots of different workshops and ecological trekking; we teach people to love mother earth, to recycle. Hopefully we will have 1000 people this year and our goal is to show everyone that you can party and have fun without those powerful and some- times really harmful drugs. It’s a very difficult thing to do but we try... And we’re starting with ourselves! Haha! BX: Do you think that trance is surely going to grow in La Paz thanks to initiatives like the Samhain festival, then? DS: Yes. I think that trance culture is growing very fast: there are more and more people at trance parties every time. Hopefully we can set a good example and teach other organisers how to really make a festival – it’s not for money that we do it, it’s for the feeling throughout and at the end. Trance is a lifestyle, and we need to take our lives far away from all dark things, dark people, dark thoughts, and start respecting our body, which is the biggest present we have.

BX: Do you feel that some of the older Bolivian music might be lost because of the new electronic movements that we are witnessing?

DS: Some music is meant to disappear, I think, but the real ancestral music will never be lost. You still get songs from 10 or 15 years ago on the radio. Though electronica might be is the future of music, the roots will always be here, and folk music will always be precious to the people here. Their minds might not yet be reader to make the transition to electronic music, but someday they will be... The younger generations seem to like

A few of Ricardo’s recommendations: • U-Recken - Holly Waters http://www.youtube. com/watch?v=FrAvb-8cQX0 (psychedelic) • Liquid Soul - Desire http http://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=7E2EYXU-Ypw (progressive trance) • Claude Vonstroke - Who’ s afraid of Detroit? http:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=xmup8AofWnw (minimal) • Shpongle - Shpongolese Spoken Here http://www. youtube.com/watch?v=1Shi9tR3GhM (chill out) • Urucubaca - ContraCultura http://www.youtube. com/watch?v=oV9zHsYZuVU (psychedelic) • Penta - Robot Poetry http://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=ff5Mr_9NmUI (night trance) • Chris Rich - The Domino Effect http://www. youtube.com/watch?v=BxSb5iIASJM (dark trance)

Download

Download