The Journey the Living Must Make for the Dead

‘Okay, so you just stay quiet because we don’t want them to find out you’re a gringo’, my friend ordered me as we walked into the main office of the cemetery. While one can learn much from the mourning rites which immediately follow the death of a loved one, I was keenly aware that this was but part of a much larger process which unfolds over weeks, even years. I set out to investigate which steps a family in La Paz has to follow after a wake. Learning about such things presents all sorts of challenges given the sensitive nature of the topic; people don't readily offer this kind of information to people who are merely curious. In order to get closer to the topic, a friend and I decided to act as if the mother of his empleada was on her deathbed and we were trying to help with the funerary arrangements. While I felt somewhat insensitive doing this—especially when I realized the couple in front of us was planning the funeral of their eight-year-old son—it showed me how Bolivians say goodbye to those they love.

Only being familiar with festivities associated with dying, I was interested in discovering what, exactly, happens when someone dies in La Paz. Having talked to some locals, including my Spanish instructor Roxana, I learnt that on the day that someone dies, a loved one washes the body, then dresses it in the deceased’s best outfit. The body remains at home in bed while friends and family pay their respects. Throughout the night, loved ones talk amongst themselves, praising and remembering the deceased. Coca leaves, alcohol, cigarettes, and flowers are placed near the body as talismans and the family begin to acullicar—chewing each coca leaf while giving the departed a compliment or speaking of a fond memory. This frequently goes late into the night; the mourners kept alert and awake by the coca leaves.

The General Cemetery is a neighbourhood all to its own. Outside its walls are flower markets, funeral homes and tombstone shops—just about everything needed for a funeral. Plaques can be personalized and tombs ordered. Prices range widely depending on quality of materials. There’s heavy marble in princess pink for those with a little extra cash and basic glass covers to decorate the graves of those less wealthy.

In the cemetery itself, there are gorgeous mausolea with ostentatious sculptures next to shoebox-sized graves with cement tombstones. The cemetery is currently divided into three sections which include cuarteles, pavillions, mausolea, sarcophagi and tombs.The variety in social class is laid bare in this anthropological library of the dead, in which innumerable bodies are stacked together. Occasional vacancies can indicate that someone’s family is no longer able to pay rent for a plot, making room for the new dead. Indeed, when one considers how ancient and packed the cemetery currently is, it’s natural to ask where the new dead bodies end up. As Jaime Saenz pondered in his seminal Imágenes Paceñas: ‘Why doesn’t the cemetery get any bigger?’. The municipality’s figures indicate that 95.6% of the cemetery is currently occupied, and that there are 15-17 daily burials. In 2008 there was room for 106,681 ‘inhabitants’, 25,330 places of which had been sold in perpetuity.

We walked into the cemetery’s administration office and asked the attendant the price of a burial plot. After giving us several brochures and price lists, the man explained how we could pay. To purchase a plot in perpetuity would cost 11,000 Bolivianos (US$1,570), or over 10 times the minimum monthly wage in the country. We were also offered the option to rent out a plot until the expected death of our empleada’s mother.

We made our way down to Avenida Busch, the Fifth Avenue of funeral homes in La Paz, the most famous of which is probably Funeraria Valdivia. As we stood outside and discussed our game plan, a man greeted us and politely asked if we needed help, so we proceeded to explain our situation. He led us into the funeral home and up a small flight of stairs to a room full of coffins. He had a distinctive used-car dealer’s hustle, a likely indication that we were dealing with a highly competitive market. The man’s routine involved walking around opening the coffins and their viewing windows built into the lids. I learnt that the purpose of these was to allow mourners to look upon the dead during the wake, as well as seconds before the coffin descends underground, or into one of the countless nichos in the cemetery. With a coffin purchase, the funeral home would pick up the body from wherever it may be (at hospital, at home), then bring it to the desired venue for a proper ceremony. Then, a bus would be provided to transport the funeral party to whichever cemetery was chosen by the family. The staff could even make the arrangements for the burial plot as part of a fully inclusive package.

The funeraria agent spoke quickly, trying to persuade us to take the deal, as if he were narrating a commercial for some type of ‘as-seen-on-TV’ household gadget. We went downstairs to see the modern funeral parlour and he continued with his pitch. Mid-sentence, he asked us how old our empleada’s mother was. “Seventy-three,” my friend said, thinking on his feet, “she’s convalescing at home...so that’s where you can plan to pick her up.”

At the end, we were given business cards as we walked out the door and we said that we’d call later that afternoon. Whilst it felt uncomfortable at times to make up a story to understand this process, it gave me a good insight.

A walk through the cemetery shows how alive these dead people really are. Flowers decorate the graves, along with some of the deceased’s favorite objects. The graves of children are decorated with candies and the elder deceased have things like candles, miniature Coca-Cola bottles, and cigarettes. It is as if the person were only sleeping, not gone forever.

Imagine being invited to a stranger’s house for the first time. Whatever you may be expecting, whether unfamiliar trinkets or obscure family rituals, the idea of encountering a so-called “skeleton in the closet” is unnerving. The idea of encountering a literal parts of a human skeleton? Unthinkable.

“Miope ñatita

Tapiada cuenca del ojo

Carcajada dislocada

Mandíbula batiendo”

‘De La Ciudad’, Rene Alejandro Canedo Peñaranda

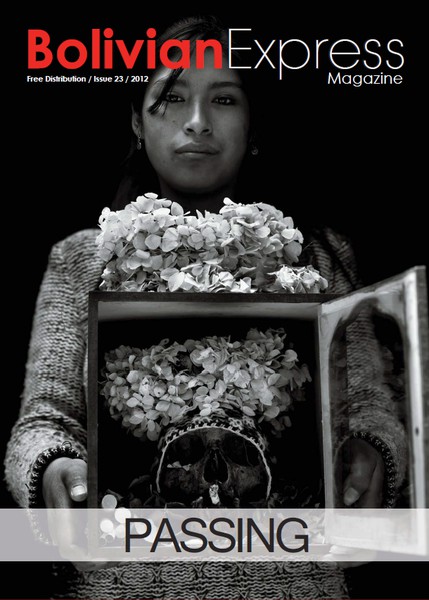

The ritual practice of keeping, adorning, and paying homage to human skulls, known as ñatitas, is a Bolivian tradition whose origins are hotly debated. It is widely believed that in return for cigarettes, coca leaves, flowers, candles, and other adornments, these craniums provide protection and good fortune for its surrogate owners.

Common lore has it that this tradition stems from the pre-Incan civilisation of Tiahuanaco. In the past, not only did chieftains and high-ranking warriors keep skulls of defeated enemies retained as trophies, but those of deceased family members were kept and cared for. However, art historian Pedro Querejazu contends that the ñatitas ‘craze’ is not as ancient as people might think, indicating that the tradition’s origins are post-colonial.

Living with the Dead

Here in Bolivia, laying out a collection of human skulls like curious knick-knacks on your living room shelves is far from other-worldly. In fact, that is exactly what I encountered at Doña Eli’s house in the north of La Paz, well known in her neighbourhood for her extensive collection of skulls and her psychic abilities. She was kind enough to grant us an interview, or as she put it, an ‘introduction to her children’.

With macabre familiarity, these skulls reside in familial harmony with their owners. The word ñatita, is an affectionate reference to the appearance of the nose bone of the skull, literally meaning ‘the little pug-nosed one’. Often, the skulls are put into pairs or groups so that they can form bonds of friendship with each other. Some even get married. Many owners organise huge parties, known as prestes, in their honour, which involve offerings of food, drink and dance.

Doña Eli firmly believes that she owes her health and livelihood to her ‘babies’, as she refers to her 53 skulls. Everything in her house revolves around the ñatitas. The shelves of skulls take up a whole wall, not to mention the ñatita-related posters and photographs of her collection. Each skull sports its own personalised hand-made hat, which, as Doña Eli explains wryly, is absolutely essential for her to differentiate them. This altar is dimly lit by offerings of candles and adorned with flowers. Far from being exclusively beneficial to her and her family, Doña Eli explains that ‘they are friends with everyone’.

This becomes apparent during the interview, with a steady stream of people coming through her curtain door in order to provide offerings for the ñatitas. ‘One man even brought a television!’ she exclaims.

The skulls, she explained, came from various places; gifts, inheritance, purchases, each with its own name and story. ‘I have lawyers, police, lovers, even millionaires here on my shelf’, she laughs, ‘and they each have their own character’. She even has several tiny skulls of infants, which hold pride of place on the shelf. Doña Eli tells us they are especially helpful to women who are trying for a baby.

When asked as to why she had amassed such a collection, Doña Eli told us that she had been born with a psychic gift, which manifested itself when she was about 8 or 9, and that she uses the spiritual energy of the ñatitas to help her. She also tells us that through these skulls she is able to communicate directly with the souls of the departed.

Forensic Skulls

Eli calls herself an ‘instrument’ of God, who works through her: she claims no power of her own. She works both with her faith in God and her faith in her ñatitas in order to help others, but firmly states that she only works for good. ‘People who come with faith and love’, she tells us, ‘are the only people I can help’. Indeed, she recounts with disgust a case of several men who had recently come to her requesting that her ñatitas cause the death of the president. She adamantly refused their offer of a large sum of money, imploring us to understand that her skulls were only ‘a force for good’.

The Homicide Department of the police force in El Alto have been widely reported to use two ñatitas: Juanito and Juanita to help solve hard cases. Fausto Téllez, a former head of this department believes that the consequences of lying to a ñatita may, in the criminal’s eyes, outweigh potential judicial punishment. It is even rumoured the police force use the skull of former president Mariano Melgarejo, who serves as a special advisor (turn to page 14 to learn more about his life and death). Yet ñatitas do not only work for the forces of good. Doña Nancy, a caserita who works outside the Cementerio Heroes del Gas in El Alto told BX that many criminals own skulls, and implore them to bring luck and provide protection from the police in their criminal pursuits.

Soul Traders

There are a number of ways of acquiring a ñatita. They can be inherited, given as gifts, obtained from the black market, cemeteries and even morgues. Milton Eyzaguirre Morales, an anthropologist at the Museo Nacional de Etnografía y Folklore, claims it is common for cemetery workers to rob skulls from graves, when relatives either abandon their dead or stop paying cemetery bills. ‘It's illegal,’ he says, ‘but officials turn a blind eye to it’. The idea is that these are almitas which have been lost or abandoned by their owners, and who are in search of new living companions to care for them. In return, these souls lend favours and care for their new keepers. Their acquisition can most accurately be described as an adoption of sorts.

This tradition has grown substantially over the last decades, going against the expected eradication of indigenous traditions by Catholicism and modernity. Their increased acceptance and popularity is partly due to the ceaseless stream of migration to La Paz and El Alto from the countryside, strengthening the position of traditionally indigenous rites in an urban environment. Belief in the abilities of these skulls are prevalent in many different social sectors of La Paz; not only among indigenous communities, but also, for example, among medical students and urban social groups associated with merchants, salespeople, and transport workers.

In contrast to the imagery associated with skulls in most Western cultures -traditionally linked to images of doom, gloom and evil- the ñatitas teach us a social way of relating to the dead rooted in reciprocity, companionship and celebration. The deceased which these skulls embody seem to belong in a different realm of the dead, a realm which maintains everyday contact with the living. As Don Simón told BX, while proudly displaying his bespectacled ñatita at the cemetery: ‘we keep Claudio on the mantlepiece in our bedroom because he is part of the family’. Unlike the souls of the countless skeletons in mausolea in the cemetery who are only offered flowers and gifts on special occasions throughout the year such as Todos Santos, these ñatitas accompany their keepers every day, and in return their surrogate-owners make them feel loved and at home. ‘How would you feel if no-one cared for you?’, Don Simón asks. ‘It’s our responsibility to the dead, it’s our duty’.

Fiesta de las ñatitas

There is no better example of the affectionate revering of the skulls than the annual ‘Fiesta de Las Ñatitas’. Every 8th of November the skulls are carried in their hundreds to the general cemetery of La Paz, where passers-by are invited to offer prayers to the ñatitas. Many of them bring crowns of flowers and gifts in return for favours. The general mood is festive and celebratory, with musicians playing upbeat morenadas and cumbias in contrast to the sombre huayños and boleros which dominate the festivities of Todos Santos, which takes place the preceding week.

On this day, the cemetery chapel holds several masses for the ñatitas. This demonstrates the amalgamation between Catholicism and indigenous beliefs that has allowed this practice to thrive in recent years. In the past, the fiesta was celebrated clandestinely for fear of repression, but nowadays thousands of practising Catholics of indigenous roots get their skulls blessed by a priest. The fiesta has changed into a pagan-religious festival: a product of the syncretism between ancient Andean traditions and Catholicism.

Conceptions of Death in the Bolivian Andes

According to the Aymara conception of the world, life is not a state but a process. Everything that exists – solid or conceptual – has an opposite companion, another side to itself. It is a polarized game between complementary opposites that attract and need each other in order to be.

In that view of the world, life and death are two sides of the same coin; one side the prolongation of the other. Death is not an end but the beginning of a new life. It’s a return to the origins, a rebirth. In the world down below -- the world of the dead -- life goes backwards. One is born old and dies young to start over again. In the world of the living, death is but a journey for the soul. A journey from the world of the living to the world of below.

We, humans, live in a realm called the Kay Pacha (or Akapacha). It’s a realm that corresponds to the here and the now. Following the principles of duality and reciprocity that govern the Aymara world, every realm has another one that completes it. Our world is therefore divided into two planes - horizontal and vertical - and then into four realms: the world of above, the Hanan Pacha, where the gods live, is opposed to the Uku Pacha, the world of below, where the dead and yet unborn reside. On the horizontal plane, the Haqay Pacha - the world of beyond - completes the Akapacha.

The conception of life and death in Bolivia is a good example of how pre-hispanic beliefs and Christianity have merged to create a unique vision that differentiates itself from other latin-american countries that share similar values. In what Henry Stobart has called a ‘calendrical coincidence’, it is remarkable that the Catholic day of Todos Santos brought by the Spanish, coincides with the indigenous festivities marking the end of the dry season and the beginning of the harvest, during which Aymaras also honored the dead. Death is not necessarily perceived as something final or macabre, it’s also a celebration of fertility and life. Death is filled with hope and anticipation for the soul to be able to start over and for the living to meet them again. As Stobart explains in Music and the Poetics of Production in the Bolivian Andes, ‘the passions associated with the early part of the rains not only concern sorrow and invoke the dead, but are also linked to sexual desire: the pent up fluids released are not only lachrymose but lso seminal’.

Upon death, the soul (ajayu ) embarks on a three-year long journey that ends on November 2nd; Day of the Dead. At the Cacharpaya - departure of the dead - the soul is finally dispatched to the Uku Pacha where the cycle can start over again. During this three-year journey to the world of below, the souls of the dead have larger responsibilities than just traveling to heaven; they have a duty to their community, a role of protection over the ones they leave, especially if they haven’t fulfilled it during their lives. The living attend the dead by offering food and drink while the spirits of the dead help provide abundant rains for the harvest.

Of course, death is still a painful event experienced by the community, however, the meticulous preparation and attention given to the wake with multiple rituals to follow is a way to help with the pain felt. Moreover, when someone dies, the soul of the deceased doesn’t leave our reality immediately, it stays there with the family during the wake and until the burial. For this reason, the body is never left unattended and is given food and drink. Somebody is always there to keep the dead company on their new journey.

During the wake, those present drink alcohol and chew coca leaves to protect them against the possibility that the soul of the deceased might turn into an evil spirit, especially if it hasn’t accepted it’s own fate yet. It might very well try to steal the soul of others to keep him company. The wake is also a moment of reflection and forgiving. The soul’s misdeeds and errors in life, as well as its success are remembered and discussed. This dialogue with the soul is a way for people to ask and for the soul to receive forgiveness before its departure.

At the burial, the soul of the dead is given everything it could need for its journey. It is believed that it will embark on a long walk and therefore needs food, drink, coca leaves, utensils, and clothes against the cold. All his favorite foods and items are buried next to him so he can leave prepared. If something were to be missing, the soul would wander looking for that particular item. Once the soul is ready, it goes on a journey, on a spiritual pilgrimage, to achieve its fulfillment in order to be ready for the next life. During this journey, the soul stays in the Akapacha. The soul will meet different spirits along his way, some malevolent that will try to trick him and some not. Eventually, the Ajayu will meet an Achachila, an ancestral spirit who will guide him and help achieve its fullness and responsibilities on earth.

On November 1st at noon and for 24 hours after, the veil between the world of living and the dead is tenuous- the souls of the dead family members are able to return. They are welcomed with special dishes and an altar is set up for them with bread, fruits, alcohol, depending on their particular tastes. Spicy dishes are prepared to entice the ancestors to come back to the world of the living - they particularly appreciate this flavor. Ladders made of bread are placed on the table to help them access our world and return to theirs. The souls can then manifest themselves as insects, birds, wind, dreams or even people. For instance, if a fly - bigger than normal - comes to eat the food, it shouldn’t be swatted away or killed, as it could be a manifestation of the soul of the deceased. Todos Santos can also mark the final stop in the journey of the soul: on the third year after their death they are finally dispatched to the Uku Pacha. The end of this odyssey marks the beginning of a new life on another world.

Alongside Carnival – which is also a remembrance of the dead – Todos Santos is one of the most important festivities in Bolivia. It is as much a celebration of life as a commemoration of the dead. The departure of the souls at the end of the festivities are marked with songs, dances, alcohol and joy in general. On Todos Santos, Bolivians welcome and say goodbye to their loved ones but also embrace the new life that awaits them. It’s also a way to thank them and honor their ancestors for what they provided them with and for the protection that they offer.

As an unavoidable part of every existence, we’ve developed a strange fascination and fixation on death and it is only natural to look for ways to cope and deal with the departure of loved ones and our own. In Bolivia, Todos Santos is a celebration, it’s filled with joy, hope and a little nostalgia - but because everything is interconnected according to Aymara beliefs, the departed don’t only live in our memories but in everything that surrounds us. They even come back on the 1st of November.

Download

Download