My Facebook newsfeed: awash with Paceña nightclub e-flyers featuring pumpkins, vampire bats and witches on broomsticks. A trip to the local supermarket and a giant skeleton dangles from the entrance alongside a temporarily erected section of rubber spiders, eyeball lollipops and fake cobwebs. Hardly something I expected in Bolivia.

October 31st arrives and the wind howls through the windowpanes of the 17th floor Bolivian Express flat. Thunder crashes and reverberates around the crater in which the magnificent city of La Paz lies; in the distance, lightning strikes the surrounding mountain peaks and the flashes illuminate El Alto and the hectically packed slopes below it. Straight out of the movies, we have the perfect conditions for a spooky Halloween party. And for Bolivians, this is exactly what Halloween is: straight out of the movies.

Fifteen years ago, the celebration of Halloween was solely restricted to the upper-class Jailon Paceños of the Zona Sur, the part of the city where a high proportion of the city’s European and North American descendants reside. I met with Micaela, a student at the Zona Sur’s Calvert American Cooperative School, who told me exactly what it was like for them.

‘Halloween is little more than an excuse for a party’, she started, ‘Nightclubs hand out flyers and people go out, without really considering what the night is all about. It’s completely commercial’. Having spent 7 months in the States studying, Micaela is one of few who are aware of the meaning of Halloween, but the days that follow expose its truly alien sentiment and lack of significance for the majority of Bolivians.

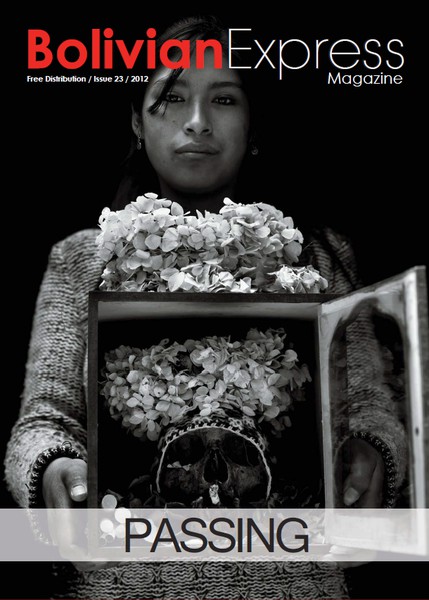

On November 1st, the Bolivian National Holiday of Todos Santos takes place, when it is believed the souls of passed loved ones will return at midday and remain with family for 24 hours before departing once again on Día de los Muertos. The complete contradiction of a night of sugar and fear induced on Halloween compared to the preparation of an immense altar of bread, fruit, alcohol, cigarettes and decorations to celebrate the return of passed loved ones, highlights that Halloween can never truly be understood by Bolivians; nor should it be.

On November 2nd, entire families from the campo arrive at the cemetery alongside those from the city honouring their dead. The children from rural areas sing hymns and say prayers in return for suspiros, bread and fruit prepared by those there to mourn. At the end of the day, these families return to their communities carrying flour-sacks of food to share with their neighbours.

Parallels can be seen in trick-or-treating on Halloween and the children who visit the cemetery during Todos Santos. Yet rather than knocking on doors, sitting greedily and gorging on their haul of ‘candy’ and chocolate, the children visit mesas and graves, praying throughout the day before sharing out the bread and fruit in their local village.

This humble idea of sharing and honouring passed loved ones on Todos Santos now lives alongside the westernisation that has resulted in the arrival of Halloween. The sheer commercial aspect dictates that Halloween is extending to wider parts of the population and is no longer restricted to the ‘Jailones’. From street vendors in El Alto to clubs and restaurants in the centre of La Paz, extensive Halloween merchandising means that it can no longer be merely seen as ‘Jailonween’.

Yet in true Bolivian fashion, the traditions of Todos Santos and Halloween will continue to exist alongside each other for years to come. While it may be a ‘calendrical coincidence’ (see p.24) that these festivities take place side by side, there are parallels that are initially difficult to spot but once discovered are hard to ignore. One rite involves children going house by house asking strangers for sweets, the other involves them going grave by grave asking strangers for bread and suspiros; one group offers extravagant costumes in return, the other offers prayers. Maybe it’s no coincidence after all.

Tantawawitas

Todos Santos, a tradition in which the living welcome and share with the dead, has existed in some form or another since the beginning of the Spanish Conquest. The apxata is prepared using traditional foods, fruit, sugar cane, onions and photographs of the loved one. T’antawawas, anthropomorphic bread representing the deceased, are one of the central offerings given to the dead on this day. At midday on the 1st of November, the almas visit the house of their loved ones and feast on the goods that have been laid out in their honour, leaving 24 hours later. Families receive the spirits with prayers and offer them the food and drink they enjoyed during their lives. Yet this tradition does much more than simply honour the dead; baking t’antawawas and giving them away in exchange for prayers brings these communities together.

It’s less than a week before Todos Santos - walking through the Max Paredes commercial district of La Paz, one immediately notices the thousands of brightly-coloured t’antawawa masks on display in street stalls. The ceramic eyes of t'anta achachis, horses, babies, cats, cholitas, and llamas stare vacantly at potential customers. As the lady at the stall says 'cada mascarita tiene su significado'; each mask has its own meaning.

Doña Lucy and her husband have been making t’antawawa masks for decades. She explains how baby-shaped masks mark the death of an infant, whereas the figure of a hatless man represents a joven. It is said that horse masks are essential as they accompany the spirits on their journeys; 'ellos llevan todo lo que se reza' - they take back with them all the prayers for the dead. For Doña Lucy, the production of t’antawawa masks is not simply a way of making a living, it is also an important family tradition. Her husband’s mother did so before he was born, and it is clear that this ritual will continue: 'I work with my children in everything I do'.

The artisan mentions how the masks 'used to be clay-white but now they are painted in a flesh-like colour'. In the last decade, novedades such as Shrek, Teletubbies, and Chavo del Ocho (a Mexican show popular across Latin America) have become a sensation, catering for parents keen to engage their children in this tradition. In order to survive it is necessary for traditions such as these to make certain concessions. In her account of Todos Santos, the journalist Cristina Ugidos mentions that traditional masks are the ones left over at the end of the season, while the ones of Shrek are the first to run out. I found scant evidence to support claims that the custom of making t’antawawas is dying. Doña Nancy, arguably the seller of the largest selection and quantity of t’antawawas in the Max Paredes, refutes any claim that this tradition is in decline: ‘I’ve been coming here since I was 15 and sales haven’t gone down in recent years; if anything they’ve gone up’.

Masas al Horno

We walk into a room filled with families - the smell of fresh bread hits you as the heavy door opens. With this sweet smell come heat and chaos; sounds of music, children and laughter. We enter a dark hot room where, in turn, dough is stacked on shelves. There are two lots - the trays where the masa is madurando, and another with dough ready to be baked. At the end of the room is a small metal door which hides the hellish amber glow of the oven. Once opened by the maestro panadero, a wave of heat rushes out. Bread is taken out, unceremoniously thrown into baskets, and carried away while raw dough is shoved in. The door is shut. The heat of the oven makes the stay bearable only for a short while.

We use the following ingredients to make our t’antawawas: 25 pounds of flour,10 eggs, 2.5 pounds of vegetable fat, water, aniseed and yeast, which together yield around 30 pounds of bread. A taxi driver told us that people sometimes offer the maestro panadero a crate of beer for the dough to be brought to the front of the queue during this busy period, especially for large quantities. It is evident that the whole economy in the ovens works in this way. For instance, the person kneading receives bread for his troubles, while the people putting dough on trays receive bottles of Coke or Fanta. In order to bake in the ovens, knowing the recipe and having the ingredients doesn’t suffice- you have to understand the social and economic norms that determine the inner workings of this hive.

I meet Doña Ascencia, who had visited these ovens for the past 6 years following the deaths of two of her children who died in tragic circumstances. Despite this tragedy, Ascencia is adamant that the spirits of her two children take good care of her and her family: things are going well in her business; she has a spot in a new development in El Alto which promises to be the largest commercial centre of its kind in the area. It’s easy to see her commercial success; her son’s 2009 Hummer is parked outside the oven’s main entrance. Baking t´antawawas is her way of taking care of these spirits just as they take care of her. It is said that the almas of the people who die before their time roam the earth for several years looking for peace, making it all the more important to adequately mourn for them.

Day of the Saints

Standing at the entrance of the General Cemetery of La Paz on the 2nd of November, exposed to the bitter wind under the heavy clouds, it is surprising to encounter such a good turnout. Thousands of people roam the vast cemetery and its surroundings; from city men in suits to children and women from the campo, some wearing no shoes.

Some have come to mourn for their dead, others have come to pray and sing for them in exchange for anything from bread to a few Bolivianos. While it is customary not to pay for songs and prayers in cash, many bands demand monetary payment. Nonetheless, this economic and social exchange comes full-circle with the bread baked and offerings being collected by the hundreds of rural families who have come to pray and play music - many leave with several sacks of food to share with their communities. In exchange for the t’antawawas we baked, two boys recite a few padres nuestros for the grandparents of a friend.

Visiting the hornos and cemetery underlined that t’antawawas are much more than a tradition, they are an expression of a cultural practice based on reciprocity. The music, colour and festive atmosphere at Chamoco Chico heightens the celebratory spirit; people come together and remember the past lives of loved ones among alcohol, laughter and t’antawawas. It’s beautiful to see how baking for the dead brings the living together.

‘Para morir no se precisa más que estar vivo'

'All it takes to die is being alive' says one of the characters in Borges’ story Man on the Pink Corner. Martha Watmough set out to investigate the deaths of notable Bolivian residents, some of which have almost become as legendary as the lives which led up to them.

Tupac Katari and Bartolina Sisa

Tupac Katari, along with his fearsome wife, Bartolina Sisa, remain to this day among Bolivia’s most influential revolutionaries.

The Aymara leader Katari, was responsible for one of the biggest indigenous uprisings against the Spanish Empire in the early 1780s. In 1781, after rounding up an army of over 40,000 people, they took La Paz under siege for a total of 184 days. The siege was eventually broken by colonial soldiers who had come from Buenos Aires and Lima.

Tupac Katari did not give up. Later that very year he laid siege again, this time alongside Andres Tupac Amaru. Despite their determination this attempt was also unsuccessful, and was broken by a loyalist group led by Josef Reseguin.

One night after a grand feast Tupac Katari was captured by royalists, tortured and quartered: while he was still alive his body was torn apart by horses into four sections. His head and his limbs were each sent to different rebel strongholds as a warning. His famous last words still resonate today: ‘I die as one, but will return as millions’.

Bartolina Sisa eventually suffered a similarly gruesome death. She was publicly beaten and raped in what is now Plaza Murillo before being hung. The International Day of the Indigenous Woman is held on 5th of September in her memory.

Mauricio Lefebvre

Lefebvre, a Canadian priest, spent 19 years of his short life in Bolivia and died a valiant death in the country which had become his home.

Born in Saint Denis, Canada, Lefebvre became an ordained priest in 1951 and the very next year travelled to Bolivia to work in rural mining towns. He later moved to Rome to study sociology, returning to Bolivia after finishing his degree. This time he moved to la Paz where he worked as a university lecturer, and later founded the sociology faculty in UMSA.

On 21st August 1971 a military coup overthrew the president Juan Jose Torres, killing dozens of people in the process, most of whom were fighting to defend democracy.

To succour the injured Lefebvre clambered onto an ambulance, tying a white pillowcase to its antenna as sign of peace. When he reached the calle Capitan Ravelo where he found the street strewn with injured students. On seeing a badly injured man calling for help Lefebvre went to help him, but was hit in the chest by a bullet as he approached the injured man. After some time the wounded man was able to drag himself to safety, but the same could not be said for Lefebvre, who was pronounced dead by nightfall.

When his ambulance was retrieved it was found covered in over 30 bullet holes; the pillowcase he had used as a peace sign was still attached. Admiration and appreciation for his act are remembered today by a plaque in the very spot where he heroically lost his life.

German Busch

The infamously efficacious and reckless Busch is perhaps as well known for his self induced death as for any other event during his time in presidency from 1937 to 1939.

Throughout his life Busch had a fearsomely determined personality. As a youth he walked around 600 km by foot from his hometown of Trinidad to the city of La Paz to prove his worth to join the army. This attempt was successful and he entered military college at the age of 18. This was the beginning of a life-long military career which saw him flourish after showing outstanding courage during the Chaco War.

He played a key part in three major military coups, the final of which led to his presidency. During his mandate he famously signed a peace treaty with Paraguay and nationalised a large part of the mining industry.

In 1939 he fell into a deep depression. He began to believe that he was not only under attack by the opposition, but that the Bolivian people had turned against him. For one whole week he failed to show up at the Government Palace, claiming it was due to toothache. He took the extreme decision to close down the Senate and Congress, and declared himself a dictator.

This breakdown reached its culmination on the 22nd of August during a party held for the birthday of his brother in law. Busch remained downstairs in his study with his guards throughout the evening, lamenting over a letter he received which brought news of his mother’s funeral which had been pitifully attended. Sitting at his desk he raised his colt pistol to his right temple and fired a shot. He was rushed to hospital and died the following day.

Some believe his suicide was fated. Busch came from a long history of family depression; his father had killed himself, as later did his two sons who also took their own lives. A truncated column stands in his honour on the site of his grave in the Cementerio General, which both represents his glory and his life which was cut short at the age of 35.

Mariano Melgarejo

Bolivia's most predictably unpredictable President, Melgarejo’s incompetence and volatility are legendary. So many tall tales have built up around his life that it is almost impossible to distinguish what is actually true about his life.

Born in 1820, Melgarejo spent the majority of his life in the military. He slowly worked his way up the hierarchy of the army, not from valient endeavours, but due to his willingness to participate in every rebellion. In 1845 he took part in a military revolt against the dictator Manuel Belzu and was subsequently tried for treason. He was pardoned, however, after he tirelessly begged for his life and claimed that he only participated in the coup due to inebriation.

After a seemingly successful coup against Arce, Melgarejo proclaimed himself President. However, Belzu had also been fighting to regain power and had control over half the army and the country. Melgarejo resolved this apparent impasse by personally murdering Belzu. A large crowd of Belzu supporters had gathered near the Government Palaces shouting ‘long live Belzu!’. It was at that moment that Melgarejo appeared on the balcony holding Belzu’s lifeless body and exclaimed ‘Belzu is dead. Who lives now?’, to which the confounded crowd cried ‘long live Melgarejo!’

Once in power Melgarejo did nothing to prove his worth as president. He viciously and ruthlessly suppressed all opposition, horrifically abused the rights of indigenous people and allegedly gave away vast amounts of land to Brazil.

In 1871, Melgarejo was overthrown by Agustin Morales and was forced to flee the country. He sought refuge in Lima, Peru, where he arrived at the building where his old lover Juana Sanchez lived, pleading for her to take him in. He insisted for several days yet she stubbornly refused. Tired of his pigheadedness, Melgarejo was shot dead by Aurelio Sanchez, Juana’s brother; a death which now seems rather befitting and almost poetic.

Arturo Borda

Tirelessly roaming the the steep slopes of La Paz, the painter Arturo Borda would wander the streets wearing an onion on the lapel of his ill-fitting suit jacket. An artist, political activist, and eccentric, he always carried in his pocket a pencil, a stray lens and a handmade notebook. A meticulous observer of everything that took place around him, he was perhaps most famous for the countless drawings, paintings and etches of the Mt Illimani he left behind.

A staunch drunkard throughout his life, the writer Jaime Saenz believed Borda wasn’t just another ordinary alcoholic who fell prey to the bottle’s corrosive grip, but that instead he was misunderstood in that he simply drank because he 'felt like it'.

In the darkness of the bitterest of winters, this septuagenarian was looking for a drink on the 17th of June of the year 1953. He roamed the empty streets looking for an open liquor store, but only found a hardware store where he demanded the owner to serve him a pisco. There was nothing there to drink, yet Borda persevered. After the owner repeatedly told him there was nothing there for him, the old man asked her to give him anything she could find. Such was his insistence, that the vexed lady gave him a container with hydrochloric acid, which Toqui Borda proceeded to drink it down in a single gulp. This is how he met his end.

Download

Download