ENGLISH VERSION

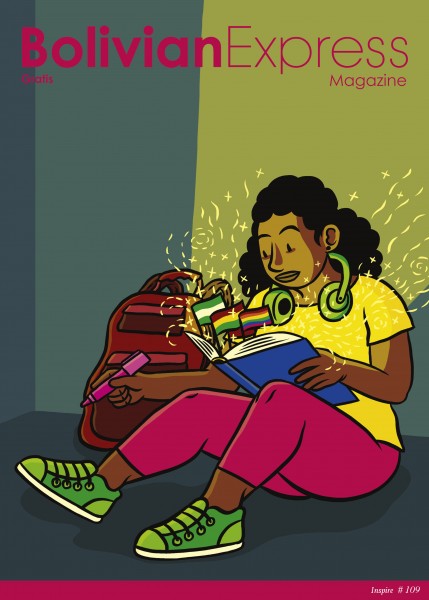

On the 2nd August of this year, in a drastic turn of events, the Bolivian government announced that all of the schools across the nation would remain closed for this academic year due to the pandemic. These events, in line with scholarly disruptions and closures across the globe, draw attention to the fact that we are not only undergoing a health crisis at this moment, but we are also experiencing an education crisis. Crucial moments in children’s formative learning years have been clouded by inconsistent online teaching, ambiguity and confusion as teachers, institutes and governments struggle to come up with solutions for their students. Access to the internet and technology to attend virtual lessons is a privilege that many Bolivian students do not have, for example. Every child in the world deserves to have an education, to have an equal chance at learning and opportunity.

This health crisis has highlighted some of society’s ugliest and most deep-rooted fissures and has shown how far we are from achieving educational equality. While a curriculum-based education is essential and solutions must be found to accommodate students as soon as possible, we too, feel the urgency and the need to address the education crisis. We are here to somehow fill a void and provide an alternative form of fulfilment for those of us who feel disheartened by the state of education. Our temporary solution to the learning crisis is inspiration.

What inspires you in your daily life? A good book, a motivational song, a powerful film, artwork, technology or humanity? Role models that we look up to inspire us with their stories of success, resilience, bravery and defiance. These people not only allow us to feel inspired by their actions, but make us act on that inspiration to create and contribute to society in the same way they have. Inspiration is cyclical in its nature: it unites us all in a never-ending chain of finding and emanating inspiration. Although some of these role models may not be educators in the traditional sense, they still provide us with valuable life lessons and an alternative source of education that goes beyond the national curriculum.

We are dedicating our 109th issue of the Bolivian Express to inspiring stories told by Bolivians. Within these (now digital) pages, you can look forward to reading about teachers, technological innovators, musicians, athletes, activists and intellectuals. While students across the world are finding ways to overcome the challenges presented by the ongoing education crisis, these storytellers have set an example by defying all odds and soaring over the obstacles that were placed in front of them. Racism, homophobia, sexism, discrimination and disability have not stopped them from achieving their goals, which makes them role models in their own right. If you are looking for inspiration and hope during these unprecedented times, you have come to the right place.

Editorial Continues...

Cogito ergo sum

Acknowledge the moment inspiration strikes and patiently let nature take its course.

When the philosopher Aristotle announced that the Earth was round, I imagine the panicked voices of people as they ran around chaotically upon hearing this news. A moment of surprise caused mass hysteria because people could not fathom an idea that was so different to their preconceptions, it would be difficult to reprogram it in their brains. People had become so complacent with their worldviews that they no longer questioned them. So, in a moment of inspiration, a philosopher's internal voice introduced a new phase in human existence. Something in the air felt different and people started changing the way they thought.

These written thoughts are all rooted in inspiration and one has to ask oneself: how is it that figures such as Nikola Tesla and Pablo Picasso were able to change history and write a fundamental chapter in our lives?

Inspiration is an obvious unknown in that it is the answer to all questions, a simple and tiny secret that each and every one of us carries within. Knowing ourselves and how to connect with the world and the energy that surrounds us could ultimately lead us to unveiling life’s mysteries.

The codes have been set. Our actions tend to be determined by a law and order that was designed by some unknown entity, and we are surprised and shocked when another person steps out of line, or acts unconventionally. We follow this order without asking why: we exist before thinking. Has anybody really understood what it means to think before existing?

From here on out, if the secret is within ourselves, and it’s our inner voice that triggers the way we act, I ask myself “shouldn’t we be true to ourselves and take risks in order to be loyal to who we think we are?”

Ludwig van Beethoven and Nelson Mandela were able to do this. They responded to their restless spirit, broke boundaries in response to their inner voice which led them to achieve incredible things. They swam against the current, thought outside of the box, and never looked back.

There is a different, more free path we can take, let’s work on steering ourselves towards it. Finally, are we heading where we want to go, or are we going where we think we’ll be loved?

-------------------------------------------------------------

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL

El 2 de agosto de este año, el gobierno boliviano anunció la clausura escolar de todos los institutos educativos del país a causa de la pandemia. Estos eventos, a nivel global, hacen hincapié al hecho de que la crisis sanitaria no es la única crisis que estamos viviendo. También existe una crisis de educación. Momentos cruciales en los años formativos de los niños se llenan con clases virtuales, ambigüedad y confusión mientras que profesores, institutos y gobiernos, tratan de encontrar soluciones para sus estudiantes. Muchos niños bolivianos no tienen el privilegio de poder acceder al internet y la tecnología fácilmente, por ejemplo. Todos los niños merecen acceso a la educación, poder aprender y tener las mismas oportunidades.

La crisis sanitaria ha resaltado algunas de las peores y más arraigadas fisuras de la sociedad, mostrándonos lo lejos que estamos de llegar a tener una educación ecuánime. Si bien la educación basada en un plan de estudios es esencial, y se debe encontrar soluciones para acomodar a los estudiantes lo antes posible, nosotros también sentimos la urgencia y necesidad de abordar la crisis educativa. Estamos aquí para, de alguna manera, llenar un vacío y brindar una forma alternativa de realización para aquellos de nosotros que nos sentimos desanimados por el estado de la educación. Nuestra solución temporal a la crisis del aprendizaje es la inspiración.

¿Qué inspira tu vida diaria? Un buen libro, una canción motivadora, una película poderosa, una obra de arte, tecnología o la humanidad? Modelos a seguir que buscamos para inspirarnos con sus historias de éxito, resiliencia, valentía y desafío. Estas personas no solo nos permiten sentirnos inspirados por sus acciones, sino que nos hacen actuar sobre esa inspiración para crear y contribuir a la sociedad de la misma manera que ellos lo han hecho. La inspiración es cíclica por naturaleza: nos une a todos en una cadena interminable de encontrar y emanar inspiración. Aunque algunos de estos modelos a seguir pueden no ser educadores, en el sentido tradicional, nos brindan valiosas lecciones de vida y una fuente alternativa de educación que va más allá del plan de estudios nacional.

Dedicamos nuestra edición 109 de Bolivian Express a historias inspiradoras contadas por bolivianos. Dentro de estas páginas (ahora digitales), podrás leer sobre maestros, innovadores tecnológicos, músicos, atletas, activistas e intelectuales. Mientras que los estudiantes de todo el mundo están encontrando formas de superar los desafíos que presenta la crisis educativa en curso, estos narradores han dado un ejemplo al desafiar todas las probabilidades y sobrevolar los obstáculos que se presentaron frente a ellos. El racismo, la homofobia, el sexismo, la discriminación y la discapacidad no les ha impedido alcanzar sus objetivos, lo que los convierte en modelos a seguir por derecho propio. Si estás buscando inspiración y esperanza durante estos tiempos sin precedentes, has venido al lugar correcto.

Editorial continúa...

Cogito ergo sum

La virtud está en reconocer el momento de inspiración, y esperar pacientemente su curso natural.

Cuando el filósofo Aristoteles anunció al mundo que la tierra no era plana, imagino un pánico entre voces corriendo por sus alrededores, un momento de sorpresa agitaba a las masas que no concebían una idea distinta dentro de un preconcepto difícil de reprogramar en sus cerebros. El pueblo había guardado de manera tan profunda una idea, que no era necesario preguntarse por qué se había acomodado allí. Y así, en un momento de inspiración, una voz interna, iniciaba una nueva fase para la existencia humana; se generaba un cambio de pensar; algo en el aire se removía.

Esta pieza de ideas escritas, relata, como base del argumento; la inspiración, y se pregunta; ¿Cómo es que personajes como Nikola Tesla y Pablo Picasso cambiaron el destino de la historia, y escribieron un capítulo fundamental en nuestras vidas?

Una incógnita obvia por el hecho de ser la respuesta a todas las preguntas, un simple y pequeño secreto que cada uno de nosotros lleva dentro. Conocernos y saber conectar con el mundo y la energía que nos rodea, podría llevarnos a revelar el misterio.

Los códigos están establecidos, tendemos a actuar según una ley y orden inventado por alguien/alguno, para sorprendernos y preguntarnos dramáticamente por qué nuestro vecino no actúa tradicionalmente, encaminado en ese invento de alguien/alguno: existiendo antes de pensar. ¿Hay individuos que han entendido verdaderamente que el pensar, viene antes que el existir?

Ahora y para continuar, si el secreto somos nosotros, y es nuestra voz interior la fuente de reacción a nuestros actos, ¿no deberíamos ser fieles a la misma, y arriesgar momentos por ser fieles a quien creemos ser?, me pregunto.

Beethoven y Mandela lo hicieron (respondieron a su espíritu inquieto), rompieron esquemas al responder a su voz interior, misma que los llevó a hacer cosas de alta calidad, remando contra la corriente, pensando fuera de la caja, moviéndose hacia adelante.

Existe un canal abierto, trabajemos en sintonizarlo.

Finalmente ¿Vamos hacia donde queremos, o hacia donde somos queridos?

Photos: Lars Baron, Revista “Las Super Poderosas”

ENGLISH VERSIÓN

How Olympic Swimmer and Coach Karen Torrez Revolutionized her Sport in Bolivia

A quick glance at Bolivia’s swimming records will tell you all you need to know about the magnitude of Karen Torrez’s career as an Olympic swimmer. She dominates women’s swimming, holding record times in 12 out of the available 22 events - 3 of those being group relays. Her exploits in swimming haven’t gone unrecognised and in 2012, when she was at the meagre age of 20, she was Bolivia’s flag bearer for the London Olympics. Not only has Torrez played a significant role in popularising swimming on a national level, but she has also gained an international platform for breaking gender boundaries and excelling in a sporting world that was historically reserved for men.

Torrez’s love for the water is unwavering. “I love water,” Torrez expresses, “it gives me a lot of peace and tranquility”. It seems fitting, therefore, that Bolivians affectionately refer to her as “la sirena boliviana” (“The Bolivian Mermaid”). Torrez recalls her first encounter with water, “I threw myself into the water without fear”. Her parents put her in swimming lessons at the age of five to combat her daredevil approach to the pool. From then on, her fearless confrontation turned into competition. “I like sports against the clock, fighting to beat your own time day by day”, she explains. This relentless mentality helped mould the sportswoman we know today, a role model for aspiring young athletes and swimmers across Bolivia. A humble character too, she told us about “the excitement of competing at home at the 2018 South American Games in Cochabamba”. This event, alongside the Olympic flag bearing, are the moments she holds closest to her.

A quick glance at Bolivia’s swimming records will tell you all you need to know about the magnitude of Karen Torrez’s career as an Olympic swimmer.

Torrez has now also become a swimming coach and feels a newfound sense of responsibility, not only for the development of the sport, but also for the future of sport in Bolivia in general. “I want to teach future generations that, as Bolivians, we can achieve great things if we put our minds to it”, she says. She decided to become a coach because she felt she wanted to give something back to the sport that had given her so much joy and success in life. As a coach, she feels the need to address the importance of sporting education in general. She stresses how “exercise is health and it is as important physically as it is psychologically”. The population needs to look beyond the advantages of sport in a physical sense and realise how sport is an essential part of human development. “It can prevent injuries and systemic diseases”, Torrez comments. In turn, the widespread promotion and insertion of this type of education could end up benefiting the country’s healthcare system.

Becoming a professional athlete in Bolivia comes with its challenges and one can only understand the hardships of Torrez’s achievements by looking at the state of swimming in the country. Torrez explains how football is the only sport in Bolivia that is played professionally, which puts her what she has accomplished into perspective. “There aren’t many athletes who dedicate themselves to any other sports [in Bolivia] for this reason” Torrez says. Football aside, there is an underdevelopment of sporting careers in Bolivia due to lack of resources, funding, and limited investment. As if these obstacles weren’t high enough, women face societal pressures that steer them away from a sporting world typically dominated by men. Things are, however, looking up. The Bolivian football team ‘The Strongest’ pioneered the first female football squad (other teams have since followed in their footsteps); Ángela Melania Castro Chirivechz, the flag bearer for the national team at the Rio 2016 Olympic Games, achieved the highest result Bolivia has ever seen in her 20km race-walking event; Noelia Zeballos, a young Bolivia tennis player from Santa Cruz, made a name for herself after representing Bolivia in the ‘Fed Cup’ tournament. Although female athletes continue to struggle for visibility and equal pay in the Bolivian sporting world, thousands of little girls across the nation now have their pick of Bolivian sportswomen to look up to.

Not only has Torrez played a significant role in popularising swimming on a national level, but she has also gained an international platform for breaking gender boundaries and excelling in a sporting world that was historically reserved for men.

Although she has already achieved so much, we cannot help but feel that this is only the beginning for Torrez. “One day, I hope to have my own swimming pool where I can open a school and a swim team”. Her love for the sport is seemingly what has carried her through to success in her field. Swimming has been popularised massively in Bolivia by the young swimmer’s success at the Olympic Games. “Almost all of the departments of Bolivia have an Olympic-sized swimming pool and all that is left to do is continue training the coaches throughout the country so that they’re able to work with prospective swimmers” Torrez says. Although there is still a long way to go for the development of the sport, the standard of training is something that can be tackled first. With Torrez being so distinguished in swimming, it only seems natural that she takes on this mantle. She has single-handedly inspired a generation of water babies, now all that’s left to do is to help them go for gold.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL

Como la nadadora olímpica y entrenadora Karen Torrez popularizó la natación en Bolivia

La magnitud de la carrera de la nadadora olímpica Karen Torrez se manifiesta, a simple vista, al ver los récords que ha obtenido hasta ahora para Bolivia, dentro y fuera de las fronteras. Se destaca por ser la gran dominadora de este deporte en el país logrando tiempos récord en 12 de los 22 eventos a los que asistió, 3 de los cuales son en la especialidad de relevos. Sus hazañas en la natación son celebradas ampliamente por el público boliviano. En 2012, a la edad de 20 años, representó a Bolivia en los los Juegos Olímpicos de Londres y fue elegida para portar la bandera nacional en la inauguración de estos. Torrez no solo jugó un rol importante en la popularización de la natación a nivel nacional, sino que también ha ganado una plataforma internacional al romper barreras sexistas y sobresalir en un mundo deportivo que históricamente estaba reservado únicamente para los hombres.

El amor que Torrez tiene por la natación es inquebrantable. “Me encanta el agua,” ella expresa, “me da mucha paz y tranquilidad”. No es de extrañar que el público boliviano la llame ‘la sirena boliviana’ como cariño a la deportista. Torrez se acuerda de la primera vez que saltó al agua: “me lancé al agua sin miedo”. Sus padres la registraron para iniciar sus clases de natación a la temprana edad de 5 años, tratando de evitar cualquier riesgo ya que ella reconoce que era una niña bastante traviesa. Desde ese momento, su coraje y confrontación de no tener miedo al agua se convirtió en su fuerza competitiva. “Me gustan los deportes contra reloj, luchar por superar mi propio tiempo día a día”. Su perseverancia e impresionante ética laboral en cuanto a sus entrenamientos ayudó a formar a la talentosa atleta que conocemos hoy, una modelo a seguir para generaciones de jóvenes nadadores bolivianos. Ella nos cuenta modestamente de su emoción de competir en casa en los Juegos Suramericanos de Cochabamba 2018. Este evento, junto a su experiencia en los Juegos Olímpicos, son sus más valiosas memorias.

Hoy en día, Torrez también es entrenadora de natación y siente cierta responsabilidad no solo por el desarrollo del deporte que ama, sino también por el futuro del deporte en general en Bolivia. “Quiero enseñar a las futuras generaciones a que los bolivianos podemos lograr grandes cosas si nos proponemos” tal como ella refiere. Torrez decidió convertirse en entrenadora porque siempre quiso devolver un poco, a la natación, de lo mucho que le dio, tantas alegrías y éxitos. También subraya la importancia de la educación deportiva en general: “el ejercicio es saludable, y es de vital importancia tanto en la parte física como psicológica.” La población necesita ver más allá de las ventajas del deporte en un sentido físico y darse cuenta de que el deporte juega un rol esencial en el desarrollo de todo ser humano, “Ayuda en la prevención de lesiones y enfermedades sistémicas”, nos comenta. En realidad, la promoción e inserción de esta educación podría tener un impacto positivo para el sistema de salud nacional.

Convertirse en un atleta profesional en Bolivia definitivamente tiene muchos desafíos y uno solo empieza a comprender los sacrificios que realizó Torrez y las dificultades que enfrentó al observar el estado de la natación en el país. La joven nadadora nos explica que “en Bolivia solo existe un deporte a nivel profesional y es el fútbol”. A causa de esto “las otras disciplinas no suelen tener muchos deportistas que se dediquen exclusivamente al deporte”. Aparte del fútbol, hay un subdesarrollo de las prácticas deportivas en Bolivia debido a la falta de recursos, financiamiento e inversión limitada. Además de esto, las mujeres enfrentan un sin fin de presiones sociales que generalmente las alejan de un mundo deportivo típicamente dominado por los hombres. A pesar de todo, han habido algunos cambios positivos con respecto a este problema en los últimos años. El ‘Club The Strongest’ fue la primera institución futbolística en armar un equipo de fútbol femenino y desde entonces, otros equipos han seguido sus pasos; Ángela Melania Castro Chirivechz, miembro de la selección nacional y quien llevó la bandera boliviana en la inauguración de los Juegos Olímpicos de Río en 2016, logró el resultado más alto en la historia de marcha atlética boliviana en la especialización de 20 km; Noelia Zeballos, una joven tenista de Santa Cruz, alcanzó la fama después de representar a Bolivia en el torneo ‘Fed Cup’.

Aunque las atletas femeninas continúan luchando por reconocimiento e igualdad en el mundo deportivo boliviano, muchos jóvenes ahora tienen la oportunidad de admirar y emular a toda una gama de atletas femeninas en el país.

Aunque Karen Torrez ha logrado mucho éxito hasta ahora, sentimos que esto es sólo el principio para ella. “Espero algún día tener mi propia piscina para desarrollar mi propia escuela y equipo de natación”, nos cuenta. Es innegable que su amor inexorable por la natación es lo que la ha llevado al éxito. La natación se ha popularizado en Bolivia gracias a la joven nadadora y su participación en los Juegos Olímpicos. “Actualmente, casi todos los departamentos tienen una piscina olímpica, ahora solo queda trabajar en la formación de entrenadores por todo el país para que trabajen con los futuros prospectos deportivos”, dice Torrez. Aunque todavía queda mucho trabajo que hacer para el desarrollo de la natación en Bolivia, la formación de entrenadores es algo que se puede abordar en primera instancia.

Con su talento, dedicación y reputación, seguro que Karen Torrez no tendrá problemas en asumir el cargo para el desarrollo de este deporte. Ella ha inspirado a toda una generación de nadadores jóvenes bolivianos, el ensamble final es promover a los atletas para llegar a obtener más medallas olímpicas.

ENGLISH VERSION

Oscar-Winning filmmaker Steven Soderbergh continues fight to have Singani officially recognised by the EEUU as the national spirit of Bolivia

While filming the movie Che 12 years ago, Oscar-winning film director Steven Soderbergh (known for films such as Ocean’s 11, Traffic and Erin Brockovich), was given a bottle of Casa Real’s Black Label Singani as a gift. He immediately fell in love with Singani and started working on a plan to export Singani for the first time and share it with the rest of the world. By forming a partnership with Casa Real, the most well-known Bolivian distillery, he created his own brand called ‘Singani 63’, which is now available across the U.S., U.K and Chile. Over the last six years, a large part of his exportation journey to the States has involved making the U.S. government officially ‘Recognize Singani’ as a “unique and proprietary product of Bolivia,” just as Tequila is to Mexico or Cachaca is to Brazil. We often forget how closely tied a spirit is to a country’s identity. “Singani has existed as a Bolivian spirit since colonial times. In addition, it is unlike any other spirit for its rare taste and it is an essential part of the country's cultural heritage” Stephan Pelaez, the brand manager of Casa Real, says . Bolivians love their Singani!

Working together with the Bolivian government, Soderbergh and his team have worked tirelessly to pressure the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) with a campaign named ‘Recognize Singani’. Unfortunately, the process behind having a foreign spirit officially recognised under U.S. law can often be long and bureaucratic. His aim is to show the government how unique Singani is as a spirit due to its distinct origin and the special requirements needed for its production (it is made from the Muscat of Alexandria grapes which can only be grown at above 1600 metres above sea level). He is also hoping to show how important the spirit is to Bolivian culture and to the Bolivian population. With these objectives in mind, Soderbergh created the website www.recognizesingani.com/spanish to give Bolivians around the world the opportunity to sign a petition to protect and promote their beloved Singani and have their voices heard.

Although the process seemed doomed after the US government rejected the proposal several times over the years, it seems there may be some good news in 2020 after all. The TTB has just put out a notice that they are in the final stages of processing the request for Singani to be recognised officially as a national spirit and they have taken on a trade agreement with Bolivia.

Bolivia celebrated 195 years of independence this year. It would be very meaningful for the Bolivian population, be it abroad or on home territory, to be able to see Singani recognised officially in time for celebrations for the nation’s 200 years of independence. Whether you prefer ‘Singani on the rocks’ or the traditional ‘Chufly’, we can all agree Singani is so much more than an alcoholic spirit.

To support the campaign to have the spirit recognised officially please visit: www.recognizesingani.com/spanish.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL

El ganador del Oscar: Steven Soderbergh continúa trabajando para que el Singani sea reconocido por los Estados Unidos como la bebida nacional de Bolivia

Mientras se filmaba la película Che 12 años atrás, el ganador del Oscar y director Steven Soderbergh (conocido por películas como Ocean's 11, Traffic y Erin Brockovich), recibió una botella de Casa Real Etiqueta Negra como regalo. De forma inmediata quedó enamorado del Singani y empezó a encarar un plan para exportar la bebida por primera vez y de esta manera poder compartirla con el mundo. Con la conformación de una alianza estratégica con la marca Casa Real, la destilería boliviana más conocida, desarrolló en conjunto su propia marca denominada Singani 63, que ahora mismo puede ser encontrada a lo largo y ancho de los Estados Unidos, el Reino Unido y Chile. A lo largo de los últimos seis años, una gran parte de su viaje de exportar la bebida por Estados Unidos se vio envuelto en tratar de que el gobierno de aquel país reconociera al Singani como “producto de propiedad y autenticidad boliviana”, tal como lo es el Tequila para México o el Cachaca para Brasil. “Singani ha existido como bebida boliviana desde la época colonial. Además, no se parece a ningún otro licor por su sabor único y forma una parte esencial del patrimonio cultural del país. Muchas veces olvidamos que tan cercana es una bebida para mostrar la cultura de un país” dice Stephan Pelaez (Brand Manager de Casa Real) . ¡Los bolivianos aman su Sigani!

Trabajando conjuntamente con el gobierno boliviano, Soderbergh y su equipo trabajaron sin cansancio para presionar a la entidad reguladora de estas certificaciones en Estados Unidos: la Oficina de Impuestos y Comercio sobre el Alcohol y el Tabaco (TTB) con una campaña llamada ‘Reconoce al Singani’. Lamentablemente, el proceso de reconocer oficialmente a una bebida extranjera bajo la ley americana puede durar demasiado tiempo y ser burocrático. El objetivo era mostrar, al gobierno americano, cuán único el Singani era como bebida debido a su distintivo origen y los requerimientos especiales que necesita para su producción (se produce con uvas de tipo Mosqueta de Alejandría que solo pueden crecer arriba de los 1600 metros sobre el nivel del mar). Con esto el director pretende mostrar la importancia de esta bebida en la cultura boliviana y para que también los propios bolivianos la aprecien de forma más tangible. Con estas metas en mente, Soderberh creó la página web www.recognizesingani.com/spanish para dar a todos la oportunidad de firmar la petición en el proyecto de promover el entrañable Singani y hacer oír las voces de los bolivianos.

Alrededor de este proceso, y durante mucho tiempo, existió un rechazo por parte del gobierno de Estados Unidos para con la propuesta de que Bolivia obtuviera la certificación sobre el Singani, pero en este 2020 parece que podremos recibir buenas noticias. La instancia TTB comunicó la noticia de que los trámites se encuentran en su proceso final al haber hecho un acuerdo comercial con Bolivia para exportar Singani.

Bolivia celebró recientemente sus 195 años de independencia. Sería totalmente gratificante y significativo para toda la población boliviana, que habita en el país o en cualquier parte del mundo, obtener finalmente la certificación de origen con la bebida nacional que representa el Singani, sobre todo para llegar con ello a los 200 años del grito libertario. No importa si prefieres ‘Singani en las rocas’ o el tradicional ‘Chufly’, todos concordamos que el Singani es mucho más que una bebida alcohólica.

Para apoyar la campaña por el reconocimiento del Sigani como bebida auténtica de Bolivia visita: www.recognizesingani.com/spanish.

Photo: Programa Lirios

ENGLISH VERSION

When I was at university, I wanted to become a teacher at some point in my life. I felt that I had a knack for teaching, perhaps it was a response to the fact that my parents were teachers. Whatever the reason was, it was a possibility. What I did not know was that my professional career would be developed exclusively in the field of education and in it I would not only find professional fulfillment, but personal joy too.

In 2015, there was the possibility of being part of a training team in the ‘Toucan programme’ (now known as the ‘Lirios Programme’), funded by the Danish Association of People with Disabilities. Human rights, gender, leadership were among other topics that we had as a basis for the training. The structure was different from what one imagines in conventional education. The project was based on the pedagogical tool of popular education, something that changed my perception of the way in which people learn. Activities, games, among others were the tools that we had to use in order to reach our target population. I do not consider myself a closed-minded person so I tried to support the team at the time with what little I knew about this method. I was still unaware of all the tools in this methodology but I was lucky enough to have a good team around me and we quickly took on all responsibility.

A great challenge arose. The people we had to work with had disabilities: there were blind people, deaf people, wheelchair users, fathers and mothers of children with learning disabilities and people with mental disabilities. This is definitely a population that makes us question what it means to be able-bodied but also how we conceive the reality of others, of people who have special needs but who have the same needs as any human being. The task was definitely complicated. Being able to create a certain dynamic, activities, or a classic presentation involved rethinking how we generated content to create something more inclusive. This meant that the material we used to train them had to be suitable in all forms of media, whether they were visual or auditory.

In the beginning, we had to face the fact that everything we had planned was subject to immediate changes. Apart from the varying physical abilities of each participant, many of our students were also influenced by economic, cultural, religious factors. Within the work group, we had people with different access to education. We could have one person who was illiterate sitting next to a university student. It seemed to be an impossible challenge. In the early days, I remember staying up until dawn with the rest of the team after the workshops had finished, thinking of new activities, new topics and making sure the content was simple, useful, but not childish, that our participants would be able to leave each workshop feeling more confident in their abilities. The challenge did not end there, because part of the role that we had taken on was not that of a teacher or instructor, but rather of a coordinator, a very common word within the NGO world, but one that is sometimes misunderstood. Such a concept determined that we did not have to usurp the classic hierarchical position on which Bolivian education is based.

What we learnt arose through debates, which were drawn from activities which we ran in workshops. We only coordinated and overlooked this process, the protagonists were the participants. Their experiences, their doubts and even their fears were what led us to decide what skills we wanted them to develop. The challenges are not straightforward. The aim of the project is to empower this sector in society, generate leadership based on democratic values, generate equality within this community so that each and every member can be an agent of change.

In Bolivia, it is estimated that 10% of the population has some form of disability

All of these aspects must be understood in a broader sense and should not only focus on disability. These individual’s lives do not necessarily revolve around their disabilities and that is why we need to be clear that, beyond the theoretical framework of the project, the workshops have allowed us to interact with people bursting with dreams, life aims, but also prejudices and fears. It is incredible to watch the evolution of certain participants: at the beginning of a cycle of workshops, some individuals seemed shy, insecure and even opposed to our methodology. We found that after each workshop, after each activity, these individuals started to feel more relaxed and this is when we, as coordinators, are able to learn more from them. In my personal experience, my perception of human limits has completely changed. This project has allowed me to understand that the unknown or the fear that stands in the way of people that are different to us, can fill us with prejudices. The idea that others are different on the basis of appearance, ability, sex, origin and many other reasons is what humans have been taught to think.

In short, after working in this field for five years; having travelled around the entire country from the altiplano, to the valleys and the lowlands; after running workshops with an average attendance of 120 participants per year; getting to know all kinds of people and learning about different people’s everyday realities, one would think that no new challenges would pop up. Yet, this work obligates us to constantly self-reflect. The challenge of educating is something that cannot be taken on by anyone, you need to be fully committed and always be open to new ideas that could benefit the people with whom you are working with.

In Bolivia, it is estimated that 10% of the population has some form of disability. Unfortunately, we are a society that is not always willing to accept disabled people as integral members of our communities. We need to understand that they are also people with dreams, virtues, but also flaws. In my opinion, education is not only a tool with which a person can learn but also one that can change an individual’s immediate reality.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL

Cuando era universitario tenía como deseo, en algún momento de mi carrera, ser docente. Sentía que tenía la facilidad para impartir educación, tal vez respondía al hecho de que mis padres fueron profesores, sea cual fuera el motivo, era una posibilidad latente dentro mío. Lo que no sabía era que mi carrera profesional se desarrollará exclusivamente en la educación y en ella encontraría una realización no solo profesional sino personal.

El 2015, se dio la posibilidad de ser parte de un equipo de capacitaciones dentro del programa Tucán (ahora llamado Lirios), financiado por la Asociación Danesa de Personas con Discapacidad. Derechos Humanos, género, liderazgo entre otros eran los temas que teníamos como base de la capacitación. La estructura era diferente a la que uno imagina en la educación convencional, el proyecto partía de la herramienta pedagógica de la educación popular, hecho que marcó mi forma de percibir la manera en cómo aprendemos como personas, desde dinámicas, juegos, entre otros eran los insumos que debíamos usar para poder llegar a nuestra población meta. No me considero una persona cerrada de mentalidad así que intenté apoyar al equipo en ese momento con lo poco que sabía sobre este método, yo aún desconocía de todas las herramientas propias de esta metodología, pero tuve la suerte de tener un buen equipo con el que rápidamente pudimos asumir el rol.

Surgía un gran reto, la población con la que teníamos que trabajar tenía habilidades especiales: personas ciegas, sordas, usuarias de silla de ruedas, papás y mamás de hijos/as con discapacidad intelectual y personas con discapacidad psíquica. Definitivamente una población que puede hacerte replantear no solo como concebimos el concepto de capacidad sino también como concebimos la realidad de los otros, de personas que tienen limitaciones pero que tienen las mismas necesidades de cualquier ser humano, definitivamente la tarea se complicaba, poder generar una dinámica, una actividad, o simplemente pensar en una exposición tradicional significaba replantear el cómo generar los medios para que todo el grupo se vea incluido. Es decir, que el material que vayamos a usar para capacitarlos tenga que ser apto en todos los medios ya sean visuales o auditivos.

En un principio debíamos enfrentarnos a que todo lo que teníamos planeado era sujeto de cambios inmediatos, porque aparte de la condición de cada persona, también influía su origen económico, cultural, religioso y finalmente, dentro del grupo de trabajo teníamos personas con diferentes accesos a la educación es decir podríamos tener una persona analfabeta y al lado otra universitaria. Parecía un reto imposible. Al menos recuerdo que en los primeros meses de trabajo, cada día después de dar los talleres, el equipo se mantenía trabajando hasta altas horas en la madrugada a replantear las actividades, los temas, que el contenido sea simple pero que no caiga en infantilismos, que sea de su utilidad, que ellos sientan que vienen a una capacitación y que salgan con la seguridad que han aprendido mucho. El reto no terminaba ahí, porque parte del rol que teníamos que asumir no era de profesor o instructor, sino de facilitador, una palabra muy común dentro del mundo de las ONGs, pero a veces mal comprendida, ya que tal concepto determinaba que nosotros no teníamos que generar la clásica posición vertical en la que la educación boliviana se basa hasta el día de hoy.

Los conocimientos tenían que surgir por el debate, producto de las actividades que damos en los talleres, nosotros somos únicamente los conductores del proceso, los actores principales son nuestros participantes, su experiencia, sus dudas e incluso sus miedos, aquellos que nos permiten saber qué capacidades tenemos que desarrollar en ellos. Las metas no son sencillas. El proyecto tiene como objetivo el empoderamiento del sector dentro de la sociedad, generar liderazgos basados en valores democráticos, generar igualdad dentro de sus mismos grupos para que cada miembro pueda ser un agente de cambio.

“En Bolivia se tiene un estimado que el 10% de la población tiene algún tipo de discapacidad...”

Todo esto hay que entenderlo más allá de la discapacidad con la que cada participante cuente, no todo en la vida de ellos gira entorno a la discapacidad, y es por ello que hay que tener claro que más allá de las metas teóricas del proyecto, los talleres nos han permitido interactuar con personas llenas de sueños y metas, pero también prejuicios y miedos. Es increíble ver que cuando empezamos un ciclo de talleres nos encontramos con individuos tímidos, inseguros de sus comentarios, en algunos casos, incluso, resistentes a nuestra metodología, son muchos elementos los que se presentan en un inicio, pero sucede que con cada taller, con cada actividad, las personas se van sintiendo más relajadas y con esto empieza el procesos en el que nosotros como facilitadores también aprendemos de ellos, y vaya que lo hemos hecho, en lo personal mi percepción de los limites humanos ha cambiado totalmente, me ha permitido entender que el desconocimiento e incluso el miedo que podemos tener frente a los que no es familiar con como nosotros hace que nos llenemos de prejuiciosos, cabe aclarar que se aplica a todas las formas en las que los humanos pensamos que el otro es diferente, no solo por su apariencia, sino también por su condición, sexo, origen, entre otros.

En definitiva después de cinco años de trabajo, de haber recorrido el país en su totalidad, altiplano, valle y llano, de haber dado talleres para una media de 120 participantes al año, de conocer todo tipo de personas y sobre todo realidades que pueden contrastar con la cotidianidad, uno podría creer que los retos se han terminado, pero este trabajo nos obliga a tener todo el tiempo una deconstrucción de nosotros mismos, el reto de educar es algo que no todos pueden asumir, se necesita una entrega constante, un replanteamiento de aquellas certezas para permitir nuevas ideas que representen un beneficio auténtico a las personas con las que trabajamos.

En Bolivia se tiene un estimado que el 10% de la población tiene algún tipo de discapacidad, y aún somos una sociedad resistente a verlos como parte íntegra de la misma, nos hace falta entender que son personas con sueños, virtudes, pero también defectos como todos los seres humanos. La educación es, en lo personal, posiblemente la herramienta con la que una persona no solo aprende más sino también cambia su realidad más inmediata.

Download

Download