Paceño writer Jaime Sáenz aptly referred to the Choqueyapu River, which runs through La Paz, as ‘the city in liquid state.’ Trash, dead animals, organic and chemical waste, rubble, heavy metals: the detritus of the city is unrelentlessly churning through the waters of the Choqueyapu. The contaminated water carries bacteria such as E. coli and salmonella which end up in vegetable crops downstream. But until the river is stopped being used as an open sewer, an alternative for this wasted water is to use it to produce flowers, like the florerías do in the Valle de las Flores, in the south of La Paz, transforming something vile into something beautiful.

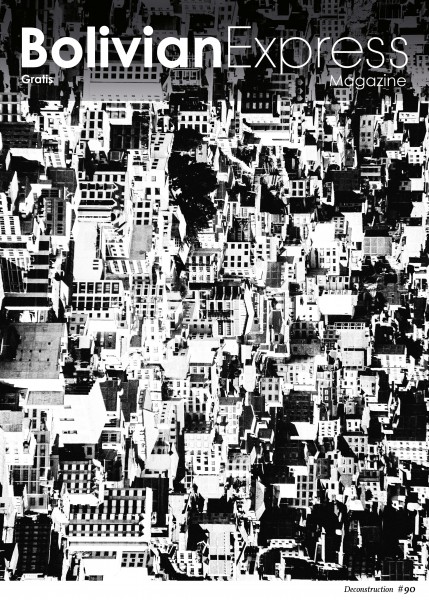

We began 2018 with our chaos-themed issue, and how when something seems confusing and chaotic, there can be an order behind it that controls it. Similarly, we are ending the year by deconstructing what is around us in order to understand it better. Bolivia is a land of contradictions – a place where spirituality and capitalism have created a unique setting, where the modern teleférico and old micros coexist, and where all the seasons seem to take place within a day. Inexplicably, it’s also a country with a capital city that doesn’t have a proper sewer and water-treatment system.

There are things that we see every day but take for granted because they are part of our routine, and because sometimes we are just too shy to ask. Why is helado de canela red (and why doesn’t it ever seem to melt)? Why are there so many dentists in La Paz and El Alto? Why do you never (or very rarely) see a cholita wearing glasses? And why do you never see a cholita without braids? And what is the actual spelling: Abaroa or Avaroa?!

We’ve tried to answer questions like these for the past nine years – in all 90 issues of Bolivian Express. Month after month, we deconstruct the ordinary and make sense out of this apparent chaos. We’ve been deciphering Bolivia’s secrets and its people, looking at what connects us and at all the nuances which define Bolivia and every part of it: the highlands, the rainforests, the Chaco and the foothills.

Ultimately, one of the things that characterises Bolivians is their perseverance and determination. Their unwillingness to stop fighting and to keep living in the harshest conditions – from the palliris in the mines of Potosí to the women selling cheese in the street whether it’s pouring rain or burning hot under the sun. Understanding Bolivia is an ambitious and arduous task, a testament to its richness, beauty and complexity.

Photo: Courtesy of flor de leche

The cheese is sublime – but that’s just one part of the story

Flor de Leche is known in La Paz for its high quality, locally produced cheeses and yoghurts. Back in 1998, it was the first local quesería to produce fine aged cheese, elevating the standard of cheese-making in Bolivia. Flor de Leche produces 42 products, ranging from cream cheese and butter to yoghurts and specialty cheeses, including Vacherin, Tilsit, Edam and Raclette, all produced and aged on site.

It started 20 years ago, when Stanislas Gilles de Pélichy, a Belgian agronomist, and his wife, Valentina Yanahuaya from the Bautista Saavedra province in the north of La Paz, were looking for their next enterprise after having worked in alternative education projects with several different NGOs. They wanted to start their own social project and, despite not knowing much about milk or cheese, they established Flor de Leche in Achocalla, a municipality 45 minutes south of La Paz.

Flor de Leche produces 42 products, ranging from cream cheese and butter to yogurts and specialty cheeses.

Flor de Leche began as a small family business; the company had its first breakthrough in 2007, when it began to participate in the Bolivian government’s maternity-subsidy-basket programme. Fifty percent of Flor de Leche’s income comes from this programme, in which all pregnant Bolivian women receive four baskets of nutritional products. Flor de Leche now works with 180 local producers, processing 3,000 litres of milk daily and distributing its products across the country – although 80 percent of its production is sold in La Paz.

Flor de Leche was born out of the vision to produce high-quality products while respecting the environment and helping the local economy grow by giving opportunities to the people living in the area. And this is precisely what happened in Achocalla.

Flor de Leche’s reputation precedes it. The company’s Roca del Illimani is the best Parmesan cheese one can find in Bolivia, and its Achocalla is a Gruyére-like cheese which leaves nothing to envy from the Swiss-made original.

Weekend visitors to Flor de Leche can enjoy pizza, fondue or raclette in the on-site chalet, accompanied by Bolivian beer and wine and finished off with desserts created by Chef Ariel Ortiz.

But more important than just being a cheese company, Flor de Leche is an ecologically and socially conscious business. The staff have coined the term ‘eco-social’ to explain how their work is framed around economical, ecological and social principles. Flor de Leche employs 35 people, most whom are women and between 18 and 35 years old, either from Achocalla or nearby towns. Teresa Gilles, the company’s strategic manager, insists that it’s about ‘revaluing the local workforce’ and giving opportunities to young people with internships and apprenticeships, which allow them to receive training at Flor de Leche while completing their studies.

‘We want to leave the least impact possible on the environment,’ Gilles says, regarding the ecological side of their work model. This starts with the Flor de Leche team, who reduce the use industrial products, and extends to the company’s water-recycling system. The acidic water resulting from the cheese-production process is treated with lye, cleaned and reused to irrigate small farms on company grounds. The whey, a byproduct of cheese-making, is rich in protein, and it benefits 65 families in the area who use it to feed their livestock.

Flor de Leche ‘is part of something bigger,’ Gilles explains. ‘People don’t know this side, what is behind the cheese… [Making cheese] is almost just a way for the [eco-social] project to live.’ That project is Granja Escuela, ‘a space for people to return to a closer contact with agriculture.’ The idea is to train people, mainly locals and youths, in sustainable ways of cultivating the soil using solar heaters, recycled water, bio-digesters and gas produced from compost. Even Flor de Leche’s composting toilets contribute to the company’s total bioavailability: wetlands and worm farms feed off the nitrogen that they produce.

The cheese-production method here has been refined and perfected to a high standard over the last 20 years – but that’s just one part of a larger eco-social goal.

The philosophy of Flor de Leche is reflected on all levels. Decisions are made horizontally via working groups, and 50 percent of the company’s revenue is invested in the community, mostly toward the funding of small social projects. The cheese-production method here has been refined and perfected to a high standard over the last 20 years, contributing to Flor de Leche’s fame and luring cheese lovers to Achocalla. But that’s just one part of a larger goal, and it is something worth paying attention to.

Photos: Autumn Spredemann

Gallery owners Fredy and Jonathan Hofmann set the stage for Bolivian artists

The doors of Arte y Cultura Galería are open seven days a week, catching the eye of all who walk by with an impressive and colourful display of work by Bolivian artisans. Only a block away from 25 de Mayo Square in the city of Sucre, you’ll find this one of a kind place that is uniquely dedicated to local artistry.

Since 2015, Fredy and Jonathan Hofmann, father and son owners of the shop, have been providing a space for local artisans to showcase their work. A far cry from the mass produced tourist tchotchke you find in so many places across the highlands, Arte y Cultura Galería has shined a light on some of Bolivia's most talented crafters, including internationally celebrated painter Roberto Mamani Mamani.

It all started with a backpacking trip in 1976, when Fredy Hofmann, who was born and raised in Switzerland, came to Bolivia for the first time and fell in love with the people and culture of the altiplano. In the spirit of a true traveler, he knew the only means of staying among the snow capped jewels of the Cordillera Real was to find a job in the area. Which is why he started working in a textile factory in La Paz.

It all started with a backpacking trip in 1976 when Fredy Hofmann came to Bolivia and fell in love with the people and culture of the altiplano.

By 1980, he had developed such an intimate knowledge of Bolivian textiles that he moved to Oruro to open a factory of his own. A few decades later, Hofmann was married and was the head of a growing family that split its time between the Swiss Alps and the Bolivian highlands.

In 2009, however, Hofmann came to Sucre for something more than just a visit. His aim was to settle in the perpetual spring like climate of the high valleys.

Given Hofmann's appreciation and familiarity with Bolivian artistry and Jonathan’s shared passion for these unique artforms, it seemed natural for father and son to create a space that properly featured local talent. When asked why he felt compelled to open a gallery in Sucre, Hofmann replies: ‘Because we didn't have one here, but we have many talented artists.’

The curatorial vision of Arte y Cultura Galería makes a difference. It offers a way for Bolivian artisans to avoid the trap of reproducing standardised cultural goods for foreign and local clients. As is evident to a traveller of the Andes, there are certain colours and patterns that repeat themselves in local artwork throughout the highlands. Instead of adhering to this standard, Arte y Cultura celebrates individuality.

The curatorial vision of Arte y Cultura Galeria makes a difference.

Every fiber, every brush stroke, every stone or strand used as a medium by a local artist tells a story of its own. It's an expression of heritage and tradition that is as singular as the pattern of a snowflake.

Image: Courtesy of Charlene Eckels

Artist Bio:

Bolivian-American Charlene Eckels was born and raised in North Carolina. She has a bachelor’s degree in studio art from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington and mainly resides in Los Angeles, California.

Eckels has travelled extensively and lived in several different countries, including Bolivia, Dubai, Bahrain, Ireland, New Zealand, London and South Korea, which has proven to be an incomparable asset in her ability to grasp diverse cultural concepts. She’s even survived a plane crash in the Amazon jungle.

Currently, Eckels is an internationally recognised Bolivian artist and a member of the Sindicato Boliviano de Artistas en Variedades. She creates works geared towards promoting Bolivian culture, the most recent of which is a bilingual colouring book.

Recent Exhibitions

2018 May fly 17 Guerrilla Play Exhibition, Seoul, South Korea

2018 Busan International Environmental Arts Festival, Busan, South Korea

2018 Yongsan International Arts Festival, Seoul, South Korea

2017 Illustrated Women in History Exhibition, Swindon, UK

Download

Download