Paceño writer Jaime Sáenz aptly referred to the Choqueyapu River, which runs through La Paz, as ‘the city in liquid state.’ Trash, dead animals, organic and chemical waste, rubble, heavy metals: the detritus of the city is unrelentlessly churning through the waters of the Choqueyapu. The contaminated water carries bacteria such as E. coli and salmonella which end up in vegetable crops downstream. But until the river is stopped being used as an open sewer, an alternative for this wasted water is to use it to produce flowers, like the florerías do in the Valle de las Flores, in the south of La Paz, transforming something vile into something beautiful.

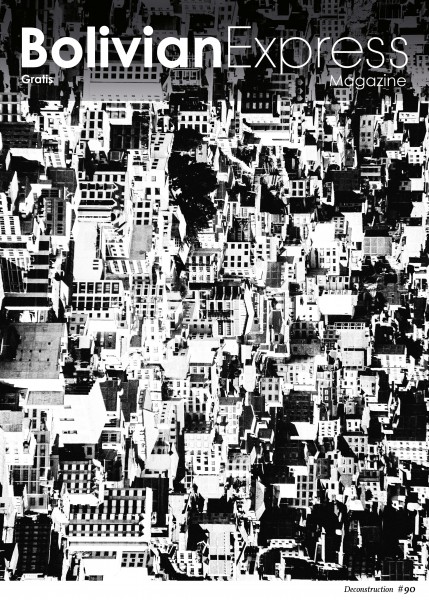

We began 2018 with our chaos-themed issue, and how when something seems confusing and chaotic, there can be an order behind it that controls it. Similarly, we are ending the year by deconstructing what is around us in order to understand it better. Bolivia is a land of contradictions – a place where spirituality and capitalism have created a unique setting, where the modern teleférico and old micros coexist, and where all the seasons seem to take place within a day. Inexplicably, it’s also a country with a capital city that doesn’t have a proper sewer and water-treatment system.

There are things that we see every day but take for granted because they are part of our routine, and because sometimes we are just too shy to ask. Why is helado de canela red (and why doesn’t it ever seem to melt)? Why are there so many dentists in La Paz and El Alto? Why do you never (or very rarely) see a cholita wearing glasses? And why do you never see a cholita without braids? And what is the actual spelling: Abaroa or Avaroa?!

We’ve tried to answer questions like these for the past nine years – in all 90 issues of Bolivian Express. Month after month, we deconstruct the ordinary and make sense out of this apparent chaos. We’ve been deciphering Bolivia’s secrets and its people, looking at what connects us and at all the nuances which define Bolivia and every part of it: the highlands, the rainforests, the Chaco and the foothills.

Ultimately, one of the things that characterises Bolivians is their perseverance and determination. Their unwillingness to stop fighting and to keep living in the harshest conditions – from the palliris in the mines of Potosí to the women selling cheese in the street whether it’s pouring rain or burning hot under the sun. Understanding Bolivia is an ambitious and arduous task, a testament to its richness, beauty and complexity.

Photo: Autumn Spredemann

Santa Cruz gives nature room to breathe in its botanical garden

Mention that you’re travelling to Santa Cruz de la Sierra and most Bolivians – mainly people who live in the smaller, quieter parts of Bolivia, like myself – will promptly inquire about your reason for visiting the ‘big city.’

This sense of wonder is not overstated.

The busy yet friendly residents of Santa Cruz, which is home to well over a million people and tens of thousands businesses, manage to balance the hectic pace of daily life in this literal urban jungle and still make time for the little things – like playing sports in Parque Urbano on the edge of the segundo anillo or mixing it up with friends and family while somehow keeping cool on a shaded sidewalk in el centro.

But a mere eight kilometers from downtown’s hustle and bustle lies a sprawling natural gem where one can find some more precious shade from the Amazonian sun: the Jardín Botánico.

An emerald haven in the midst of the vast metropolis, the Jardín Botánico raises the bar for green spaces in urban areas with an astounding 186 hectares of well-preserved forest and six kilometres of groomed hiking trails.

This urban forest currently thrives in its new location, after a catastrophic flood washed away the original garden (and part of the city itself) along the banks of the Río Piraí in the early 1980s.

The garden offers myriad opportunities to learn about a diverse array of Bolivian flora and fauna – from its orchid house, which boasts a stunning variety of flowers in bloom, to educational lectures and self-guided nature walks. And for those who are brave enough to spend a night in the jungle, there’s a campground (just be sure to make arrangements in advance).

Sharp-eyed visitors, or those who have an experienced guide, may spot an occasional sloth or caiman. During my visit, I almost tripped over a baby caiman while hiking on the garden’s trails, so be sure to watch your step!

Sharp-eyed visitors may spot an occasional sloth or caiman.

However, even if you don’t have the expert eyes of a guide, you´ll be able to spot numerous species of birds chattering away in the trees. The garden’s observation tower will also give the visitor an up-close view of these lively birds, along with a panoramic view of the city’s urban maze stretching toward one horizon while a living canopy of green stretches into the other.

The garden also functions as an important oasis in the ongoing uphill battle of preservation that faces the entire Amazon River basin. As industrial expansion reaches ever deeper into the ‘lungs of the world’, places like the Jardín Botánico will become much needed refuges for more than just city dwellers looking for a weekend hike.

Long before the city of Santa Cruz occupied the Amazonian plains, the seasonally flooded Chaco region and the subtropical forests of the area met in this same location, creating a unique ecosystem of rich biodiversity that can still be enjoyed today, although urbanisation encroaches more and more every year.

The lasting imprint of this merger is amazingly well preserved in the Jardín Botánico. It serves as the a perfect escape for those who fancy a walk on the wild side without the hassle of leaving the city. But be sure to bring bug spray, sunscreen and, above all else, a sense of adventure.

It’s a perfect escape for those who fancy a walk on the wild side without the hassle of leaving the city.

Photo: Ivan Rodriguez Petkovic

De-stressing with crash therapy in La Paz

Your heart beats faster and faster in your chest, your palms become clammy, your head starts to pound. Stress is an illness that affects all of us at one time or another, especially here in La Paz, ‘the most stressed-out city in Bolivia’ according to Jaime Fernández Hervas. Be it the result of a demanding workplace environment or an overwhelming personal life, stress can be extremely damaging if it is not dealt with effectively. That’s why Carla Calvimontes Sánchez and Jaime Fernández Hervas decided to open their crash therapy centre in La Paz, called ‘Desmadre’, meaning ‘chaos’ in Spanish. Having experienced the pressure of working in both the public and private sectors, they found the most effective method of stress-relief was through this unusual form of therapy.

Their alternative method for de-stressing is a new and increasingly popular technique that involves releasing negative emotion through the destruction of objects. You can scream, shout, graffiti walls and even smash glass bottles in this safe space, equipped with safety uniforms and health and safety precautions. Exploring your anger and anxiety in a healthy way is encouraged. ‘In your home, you can’t smash objects, you can’t scream,’ Sánchez notes. At Desmadre, however, this extreme display of emotion is not off limits.

Clients may be driven to explore crash therapy for a variety of reasons, including partners who hope to resolve a dispute, office workers who want to release pent-up frustration or even children with too much energy. ‘A mother phoned me crying,’ Sánchez recalls, ‘because her daughter was experiencing terrible bullying at school and had to leave school half way through the year because she couldn’t sleep, she couldn’t eat.’ After a session of crash therapy, she slept well for the first time in weeks.

According to Sánchez, psychological studies conducted in Spain support these results as ‘a way of easing hypertension, depression and stress’ he says. ‘De-stressing is the same as having fun’ and with crash therapy, destressing couldn’t be more exhilarating. You can even choose from ‘rock or electronic music’ to set the ambience for your ten minute stress-relief session.

At present, the only objects you can destroy at Desmadre are glass bottles, but this wasn’t always the case. According to Hervas, it’s the visual impact of smashing a glass bottle that makes this object superior in this form of stress relief . ‘We used to have glasses, glass bottles and plates,’ he says, ‘but now we only use glass bottles. All the objects destroyed during the therapy end up in a recycling centre where they are sustainably disposed of.’

In this bustling Bolivian city, ‘road blockades, marches and protests are almost a daily occurrence,’ Hervas explained. These are symptoms of a ‘stressed-out city’ in need of an effective cure. According to an article by Página Siete, ‘70 percent of Bolivians suffer from work stress.’ After its success in Spain and the United States, Hervas believes crash therapy could be the answer La Paz has been looking for.

For this reason Desmadre hopes to move to a new location in the centre of La Paz and provide therapy to city workers. Hervas believes his future clients will be able ‘to leave the office and in ten minutes be at their crash therapy session’ at the end of a stressful day at work. Although it is important not to confuse crash therapy as a replacement for traditional psychological help from a trained professional, it can definitely be a stress-relieving addition to complement psychological treatment.

The rules: you can’t bring any form of weapon into the therapy room; you can’t be under the influence of alcohol or drugs; you must wear closed toes shoes and sport their safety uniform, which includes a jumpsuit, gloves and safety visor. Apart from that, let loose!

Scrawled across the white brick wall of the reception are hundreds of signatures from clients who have already benefited from this therapeutic experience, that opened only a few months ago. One message read: ‘We are deconstructing ourselves in order to reconstruct ourselves again.’ At Desmadre, you can too begin to break down your negativity in order to construct a new stress-free life.

Photos: Sophie Blow & Adriana Murillo

The creative movement bringing Bolivian culture to an international stage

La Paz is a city renowned for its urban anarchistic creativity. From malabaristas who perform acrobatics for cars stopped in traffic, to the sprayed cursive script of the grafiteras of Mujeres Creando and the increasing popularity of hip hop tracks in the city’s club scene. Although hip hop culture emerged as an afro-american artistic movement in New York during the 1970s, it is now gaining momentum in Latin America. More and more artists, like the Bolivian girl group from El Alto called Santa Mala, are using the power of hip hop to convey cultural, political and social messages on an international stage.

Hip hop is a culture made up of four elements: break-dance, rap, graffiti and DJing. Nano, a local graffiti artist, explained that each element is a way of sharing Bolivian culture, be it through smart rap lyrics, synchronised edgy body movements or controversial imagery gifted to the streets. Through these four media, it is possible for these artists to share their vision of culture and society.

Street art is perhaps the most prominent display of hip hop culture in La Paz, a city known for the dominance of coloured murals. La Paz attracts visitors from across the world, who are eager to see how graffiti artists and muralists have intervened in public spaces to communicate Bolivian culture in the streets. Having seen how graffiti has enriched the streets of La Paz, art student Indira Zabaleta Inti enrolled in a new graffiti school called Las Wasas, while Silvia Bernal Lara and Isabel Illanes Aguilera joined a grafitero collective, to transform their passion for graffiti art into a career.

According to these grafiteras, it is important not to confuse murals with graffiti. To the naked eye they may look the same, but there is one crucial difference: one has permission from the government, while the other is illegal. ‘Because [graffiti] is illegal, people don’t respect it’ in the way they respect murals, Aguilera says.

‘Because [graffiti] is illegal, people don’t respect it.’

The illegality of graffiti gives this art form a temporary role in a community, unlike murals that can occupy spaces for decades. When someone enters a space illegally and produces graffiti on the wall, the work is no longer theirs. They are gifting a community with a message. As a result, the artwork is often destroyed due to its anarchistic presence: ‘Yes, [my graffiti] is a reflection of my identity,’ Aguilera explains, ‘[but once I have finished] it’s no longer mine.’

The anarchistic nature of graffiti art, which usually conveys a violent or controversial message, sets this creative movement apart from that of mural art, which seems to prioritise aesthetics over promoting a social cause. ‘Graffiti isn’t there to look aesthetically pleasing,’ Lara says, who became fascinated by how graffiti can make people question their society and culture. ‘It is really important. It’s what we need to do,’ she adds. ‘Sometimes we need to do more, we need to make people a bit uncomfortable.’

‘Graffiti isn’t there to look aesthetic, sometimes we need to do more, we need to make people a bit uncomfortable.’

Rap is another core element of hip hop culture that involves sharing Bolivian culture through words rather than visual imagery. ‘Every country has its own hip hop culture,’ Nano says. There are local songs performed in indigenous languages, such as in Aymara. This unique fusion between Bolivian and American influences is attracting international attention, including foreign documentary makers who are keen to explore this up-and-coming urban scene. According to Nano, even though the lyrics may sometimes be in English, a language that doesn’t represent Bolivia, the social messages are always the same. That is what really represents our culture.’

Another component of hip hop culture is breakdance. Five years ago, Nano was part of a break-dance group called ‘New Voice’, which combined elements of the hip hop movement to create a Bolivian twist on American hip hop culture. Beyond the breakdancers, the group features DJs that mix Bolivian music with an American hip hop influence. ‘It’s a way of identifying with your own culture,’ Nano explains.

Rodolfo Alarcón, otherwise known as DJ Rodo, has embraced another another aspect of hip hop that allows young people to share their views to an international audience. Rodo fell in love with the art of rap at church and discovered the versatility of hip hop as a medium for sharing important social messages. His passion for spreading a valuable message led Rodo to pursue a career as a DJ, originally in people’s homes, but now at festivals around Europe and South America.

‘There are two sides to hip hop,’ Rodo explains, ‘the commercial and the social,’ even though the commercial side of this culture is often seen as something negative. ‘When someone has an event that is sponsored by a brand, people think of them as someone who has sold out,’ Rodo says, ‘someone who doesn’t understand hip hop.’ But Rodo doesn’t see it this way. ‘It’s a platform to show what we do. If I just do hip hop on the street, no one will see what I do,’ he says.

The other side of the coin, the social side, involves sharing a message and, thanks to online live streaming, Rodo can share his passion with a global audience. This is something that all hip hop artists aim to achieve: to share their views through the medium of this anarchistic cultural movement.

Hip hop is a culture in perpetual evolution, a movement that is continuously adapting and finding innovative ways of pushing the boundaries. As a result, Rodo isn’t content with all that he has achieved so far. ‘My last event was disappointing,’ he says. ‘When I was a DJ for Red Bull, the venue was packed with people.’ Just like the culture of hip hop, Rodo feels the need to keep evolving. ‘It’s time for me to deconstruct what I’ve achieved so far,’ he says, ‘and reconstruct something better.’

Download

Download