Violence constitutes an inherent and quotidian part of club football worldwide. In South America, barras bravas – supporters’ groups cut from the same cloth as European Ultras – are the culprits held responsible for this rise in bellicose hooliganism. Alex Walker speaks to former and current members of Club Bolívar’s La Vieja Escuela to discover what the future holds for Bolivia’s barras bravas.

You come to a stop after a thirty hour bus ride. Roadblocks set up by opposition fans outside the city meant that your journey was delayed by several hours. The bus is sweltering, a heady fug of paceño sweat clogging up your olfactory senses. It is 1pm: match day. You scrawl provocative messages in black marker pen on white banners. You spend an hour tearing up last weeks’ copies of El Diario for that split-second when the team emerges to a shower of printed letters. Then, you drink. The match begins, you can barely hear your voice through the relentless barrage of racism coming from across the stadium.

The opposition score. The place erupts. You try to sneak away ten minutes from time but when you step out onto the side street, your escape route is blocked. 15 opposition fans spread ominously across the road. There are no police in sight. Their leader, his gold tooth momentarily blinding you as it catches the disappearing sunlight, pulls up his sleeve, revealing the single word ‘Blooming’ tattooed across his bulging bicep. He rips off your shirt, sets it alight with his zippo, throws it to your feet, spits on its navy badge, turns away, zones in on his next victim.

It hasn’t always been like this. As one Bolívar fan recalls, ‘in the ’80s and early ’90s everything was friendly’ and opposing barras would amiably share the general stand; quite a contrast to the mandatory separation into the Curva Norte and the Curva Sur at Estadio Hernando Siles today. Bolívar’s barra, La Vieja Escuela , formerly Furia Celeste , was formed in 1995 by a group of youths, primarily university students, following in Argentina’s footsteps 40 years earlier. Ominously, Argentinian football had become increasingly bloody with the emergence of such barras; a situation that culminated in 2002 with a season that claimed the lives of five supporters and left numerous others with bullet or stab wounds.

Bolivia has clearly not quite reached these levels of aggression. For instance, since the inception of the Furia Celeste , almost 20 years ago, there has been just one reported death as a result of its action —a ‘The Strongest’ fan tragically beaten to death in ’98.

I stumbled across a cartoon that aptly captures the nature of violence in Bolivian football today: it depicts two Argentinian fans scuffling, two English fans exchanging blows and a Bolivian fan sitting behind a computer battling his opponents through the medium of Facebook. The real underworld of Bolivia’s barras bravas , then, can be found in the attitudes —though not as much in the actions— of their members: verbal aggression and taunting are commonplace but violent incidents are relatively rare. That is not to say that physical aggression between barras bravas is a dying phenomenon—quite the opposite.

In Santa Cruz, according to Javier, a former member of La Vieja Escuela , ‘win or lose, the fans clash’. He explains that while ‘all violence in La Paz is spontaneous’, elsewhere it has become increasingly organised. Football, crucially, has also become ‘a platform for a political agenda’. In fact, in Estadio Ramón Tahuichi Aguilera, Santa Cruz, banners demanding ‘autonomía’ have become a staple of match day protests.

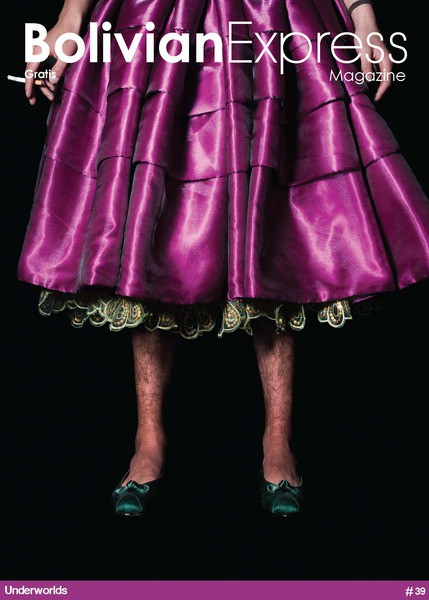

Esmeralda, aka Cholita Fox, an icon of La Vieja Escuela –the only cholita to belong to a Bolivian barra of this nature– explains that barras are a reflection of their city: ‘your club identity and your regional identity are linked’. She adds that today there are more female than members in La Vieja Escuela . Santa Cruz, for example, has a notably regionalist identity and the barra, consequently, is notorious for its racist chanting.

While the violence that accompanies the rise of such organisations is certainly a cause for concern, there may well be a more pressing one. In the 1950s, the barras of Argentina started out, much like those of Bolivia, as groups of dedicated fans who received free shirts and tickets by officials who needed votes by season-ticket holders so as to get elected onto club boards. Once these fans had their foot in the door, however, they began to turn the screw and increase their demands, resorting to extreme –often violent– measures to tighten their grip on the club’s hierarchy. The barras of Argentina, allegedly, take hundreds of thousands per annum though controlling ticket sales, club merchandise and refreshments within the stadiums, much like a mafia organisation would. More alarmingly, though, is the claim from Gustavo Grabia –an Argentine journalist and corruption investigator– that larger barras also receive up to 30% of outgoing transfer fees and 20% of certain players’ payslips.

This is an ominous warning sign for Bolivia where the culture of barras bravas is still in its initial stages. Although it can clearly learn from Argentina’s mistakes, Bolivian football may well have already condemned itself a silent slave to its burgeoning barras bravas .

Life Continues Inside the Women’s Prison of Obrajes

Her name in English means ‘hope’—ironic and perhaps understandable, then, that her eyes betray her as lacking in her namesake.

Nestled between high-rise apartments and post-apocalyptic rock formations sits a settlement inhabited solely by women. This is ‘la cárcel de mujeres’, a low-security prison for Bolivia’s female offenders, located in the relatively affluent Obrajes barrio of La Paz.

On first impression, it feels more like a village than a jail, save for a watchtower and burnt-orange walls that surround the courtyard. But la cárcel houses 360 women serving up to 30-year sentences for crimes including murder. Petty thieves and drug addicts mingle with violent criminals. Amongst them roam 62 children.

The prison is essentially a functioning community, albeit an atypical one. Inmates here have jobs from cleaning toilets to packing snack boxes with sandwiches for Bolivia’s state-owned airline. There’s a lavandería where garments drip over women kneading soapy piles with bare hands, and a chapel, a kindergarten and several tiendas.

A view from the bleak room we’re ushered into to conduct interviews reveals a ramshackle mélange of metal roofs brightened by sodden clothing in every colour drying in the late-morning sun. One woman dyes the tresses of another a disconcerting lilac hue, wringing excess slosh into a washing-up bowl. Sandals and lopsided toys lie discarded on the walkways separating toldos (small, slum-like spaces where prisoners sleep and spend time), which are the metre-square ‘rooms’ where time is passed when the women aren’t working or studying. This isn’t the type of establishment where inmates are enclosed within four walls every day. Instead, hours are filled in a variety of ways.

‘We have four roll calls per day’, explains grandmother of 10 Patricia Arduz, who has been incarcerated for 13 years for a crime she’d prefer not to tell us about. The 59-year-old has a petite frame and a warm personality, with smile-wrinkled eyes and crucifix jewellery in abundance.

‘I arrived at Obrajes last year, and it’s far better than where I’ve been before’, she explains. ‘Besides the roll call, we choose what to do. You can watch TV, play sports, work or take classes.’

The women in la cárcel have the opportunity to study courses, from English and social etiquette to therapeutic dance and reusing aluminium. ‘I don’t work here, but I make clothes which sell well on the outside’, Patricia says. ‘One item goes for up to 250 bolivianos.’ She smiles proudly as she holds up knitted mittens for us to admire.

Another prisoner, 24-year-old Esperanza Chambi, says that she’ll spend her afternoon partaking in a hairdressing class. ‘I’ve learnt a lot here: sewing, knitting, making clothes. I’m also vice president of the [inmate] population. I look after the other women and they respect me’, she says, with little tangible enthusiasm. Esperanza is six years into a 30-year sentence for murder—the maximum allowed under Bolivian law. Her name in English means ‘hope’—ironic and perhaps understandable, then, that her eyes betray her as lacking in her namesake.

‘It was accidental murder’, Esperanza says, hesitating before describing her crime. ‘I worked in a Chinese restaurant and started fighting with another employee. I pushed her, shouting, “Go away!” But she fell and hit her head. I ran away, but the police found me.’ Esperanza has reluctantly become accustomed to life in jail. ‘I’ve changed since being here’, she admits. ‘I’ve changed the way I think. Maybe outside will be worse. Maybe there is a good reason I’m here now.’ She speaks chillingly, tone hollow and eyes expressionless.

She’s not the only one who is unsure of what life in el mundo exterior might hold.

‘I’m leaving the jail in a couple of weeks’, explains Patricia, fear permeating her voice. ‘It’s not going to be easy after 13 years—there’s everything you need here. I’m afraid because I don’t know what people’s reaction will be. They might hate me. I’m afraid. I’ve been here for a long time.’

Twenty-six-year-old Helen Pereyra, who has two Bolivian parents but a misleadingly fair complexion, served one and a half years in la cárcel. ‘Settling into Obrajes was difficult. The women were unkind, calling me “la leche”, she remembers. ‘I tried to keep a low profile—they threatened to cut my face like they did another fair-skinned woman. In the first week I cried because I was scared and missed my daughter. Then I took sleeping pills that I got from a guard to try and forget.’

Readapting to the real world even after a relatively short sentence was just as challenging, Helen says. ‘It was strange being in the city again—working, traffic, mobile phones. It was like being reborn.’ Since leaving la cárcel, Helen has returned to living with her daughter. She was four when her mother was imprisoned for falsifying government documents with her father, who is now serving three years at San Pedro. ‘I didn’t want my daughter to live with me’, Helen tells us. ‘I decided to be strong for myself, but in prison children learn bad things.’

Sgt. Nancy Villegas, a guard of seven years, agrees, and her concerns are confirmed by the general director of the Obrajes jail. We sit in a high-ceilinged office with an ornate light fixture and a wooden desk. The two women face us, attired in khaki-coloured uniforms and polished boots.

‘My good experiences here are mostly with the children’, Villegas says. ‘I’m always there to protect them. But children suffer. They don’t belong here.’ She is straight faced as she elaborates. ‘Mothers are under pressure, and they take it out on their children. It’s not [physical] violence but psychological; they lose their patience.’

Bolivian law allows infants to live with their parents until the age of six. La cárcel is home to 51 children that fit the criteria, but 11 others, the oldest aged 12, live here too. Sometimes three share a single bed with their mother in a dormitory sleeping up to 40 inmates. ‘We have a team whose obligation it is to provide health care, social work and work in conjunction with other institutions’, prison director Luz Alaja Arequipa explains. ‘But children shouldn’t be here. They have nowhere to play, and when they’re old enough to attend school they face bullying and discrimination.’

Walking around la cárcel, however, I can see that the children here are happy. Rosy-cheeked toddlers sip juice and run around the courtyard. One young girl sits cross-legged on the concrete, feeding spoonfuls of pasta shells to a baby sibling in a cardboard box cot. She giggles and says ‘buenas tardes’. Another plays hide and seek, weaving between toldos

draped in flowery sheets and women shielding their faces from the sun with Tupperware lids.

Some argue that the children are better off living with their mothers, no matter how unnatural the environment, given the alternative of being cared for by potentially untrustworthy or distant family members. Esperanza is perhaps proof of this. For the first two years of her time in la cárcel, Esperanza’s daughter, now six, lived with her.

‘When my daughter was here she went to the kindergarten’, Esperanza says. Now, however, she and her eight-year-old brother live with their father in the countryside 12 hours away. ‘They don’t visit often anymore, just once a year in December. I’m here for 30 years, but the worst punishment is that I can’t see my children growing up’, she says, letting her steely-eyed defence down as she sobs, speaking at an increasingly inaudible volume. It’s moving, a true indicator that the women here are more than the criminals that they’re labelled as.

‘When I left Obrajes, employers couldn’t see past my criminal record and old friends didn’t want to know me’, former prisoner Helen tells me over a coffee. ‘People can’t see past the fact that I’ve been in prison. It makes me so angry. But the experience formed a part of my life and that won’t ever change.’

It’s hard to leave Obrajes with an attitude void of positivity. Before the visit comes to an end, grandmother Patricia, who is set to leave within the next few weeks, shows us around her toldo. It’s small, cosy and brightened by slightly wilting yellow flowers in a coffee jar vase. It’s wallpapered with a collage of faces of beautiful women, cut from glossy magazines. Why? ‘I chose this because I like to see the happy, open smiles of women’, Patricia says, beaming and becoming one of them. And that’s the thing that surprises most about la cárcel : whilst there are faults in the system and gaps are fallen through all too often, at the same time, there are happy people here.

‘Sometimes the women are playing and chatting and forget that they’re in prison’, says guard Nancy. ‘That’s the most rewarding thing about my job. I feel more human working here.’

IT´S A COMMUNAL THING

Nothing quite defines the seedy underworld of La Paz quite like its many ‘adult cinemas’ or cines privados, as they are called. Watching a bunch of old men sitting together calmly watching what most would consider hardcore porn beamed from a cheap overhead projector is surreal, alongside watching them ‘go to the toilet’ every five minutes, leaving promptly afterwards. As if the dark, smoky room isn’t bad enough, the films themselves will also leave one questioning whether the final triumph of barbarism has already arrived. With an entry fee of just 10 bolivianos, one can watch three hours of feature-length adult films with their comical ‘storylines’ (or rather lack of). One is reminded of the That Mitchell and Webb Look sketch in which David Mitchell plays a porn scriptwriter and explains the complexities of the job: ‘It’s really easy, basically, I get a piece of paper with “they have sex” written on it eight times, and I just have to fill in the blanks, simple’.

Of course the first question one is left with is why men would go to such a public place to watch this type of film. In the UK, such cinemas aren’t a common sight: with DVDs and the Internet there isn’t any reason to go to such a communal place. But the demographic at these cines privados is clearly older married men, whose wives might not approve of these films. After all, a single person would surely rather enjoy these films in the privacy and comfort of their own home. (In fact, at various points in the cine, men would receive calls and quickly reject them—no doubt their long-suffering wives.) Secondly, the reach of the Internet is different in Bolivia than it is in the West. In Europe, almost everyone has access to it in their own homes, and most have multiple connected devices. However, in Bolivia, with home Internet costing the same as in the UK, many ordinary Bolivians are priced out. Only around 30 percent of Bolivians have home access, compared with 83 percent in the UK. As a result, many Bolivians typically rely on cheap public Internet cafes—not the best place to access such explicit material.

Is constitute a tiny, privileged, and often foreign elite. The contradictory world of cheap overhead projectors and white Western actresses makes it a bizarre but thoroughly depressing affair, certainly not a recommendation for those sightseeing in the city.

Download

Download