There’s something decidedly tribal about them. They are always armed, often with multiple weapons. They wear identically olive-green, seemingly bulletproof uniforms. They act instinctively. Like members of a cult, they stand by secrecy and hierarchy. They are united by a shared cause—to serve and protect. The tribe that is the Bolivian police is comprised of individuals with individual needs and desires, united for the nation and love of the law. Ironically, indoctrination by the law itself has stifled members of the institution, and in recent years they have been subject to under-appreciation from an overly-critical population. These challenges have brought about a renewed quest to reclaim their rights and discover an identity.

According to sociologist Juan Yhonny Mollericona, a great 'insecurity' has swept over Bolivia. Crime in La Paz rose dramatically from 1995 to 2001, increasing more than threefold, but through modernization efforts crime has decreased in recent years.

Today, the demand for further police modernization is apparent. After a failed attempt to institute a model of communitarian policing in 1999, this initiative has been given new life at the start of 2013. In cooperation with the British Ambassador Ross Denny, the police have been putting into practice this model, which has as one of its main components the requirement that policemen devote greater time to foot patrols, as a way of integrating them further with the local community.

Historical Tensions

On the surface, it’s just an institution. But being part of the police force in Bolivia means more than this, bringing with it a history fraught with subjugation, both of its members, and of the police in relation to other, more powerful, institutions. The Bolivian Police has historically been separated, tribalized by its tensions with the government and the military, a struggle that has been salient since 1949, when the police began demanding social and institutional reforms.

During the National Revolution (1952-1954) the police distanced itself from the government, and the military took its place—forming a military-government alliance that for the next fifty years would manipulate the police as an instrument with which to further a set political agenda. Inevitably, this separation further weakened the already underdeveloped institution. In 1965, the Police was reduced to its lowest institutional level under the command of the military. The police’s existence was trivialised, as policemen were only called upon when needed for assistance. Historically, the military has been the privileged group, receiving higher pay and benefits from the government. Today, on an institutional level, the relations between the police and military are cordial on the surface, though both institutions have been scarred by their problematic shared past. Latent resentments stew underneath the surface only to spill over at critical moments, such as those of February 2002, when far from helping to keep the peace, both forces used firearms against each other. Since then, both institutions are often called upon to work together in times of conflict or social unrest. Individual officers nevertheless express resentment towards the military, an institution they still consider more privileged.

During the first term of Hugo Banzer’s dictatorship in the early 1970s, the Doctrine of National Security turned the eye to the security of both the state and society. Action was then taken to improve the Police Institution, bringing upon the era of Militant police that were charged with the responsibility to control society, fight against delinquency and social marginality.

The militaristic aspect is still more than residual. I asked an officer why he was poised so readily to shoot, his hand on the trigger, on a barely busy street corner. As if reading from a script, he replied, 'it’s only for show, to keep the peace'. As he said this, his eyes were forward, his posture tall, forming sentences as if he were swearing by a book.

Through the national shift to improve internal security, the Bolivian Police floated with the tides of the nation’s needs, its own needs being disregarded; it represented a utility rather than an independent institution. The purpose and identity of the police was still unclear, and so were assimilated by the military and made to focus their attention on gathering military intelligence to battle drug trafficking.

In his book ‘Policía y Democracia en Bolivia’, former Minister of the Presidency Juan Ramon Quintana recounts how 'the police were converted into a docile instrument that supported not only the repressive structure of the government. Expanding upon its traditional functions, they took increasing part in corruption and delinquency in favour of the government’s rule’.

Present-day struggles

The issue is rooted to the fact that the police are a single national tribe rather than a clan with different bands and kin-groups. Because the police institution is structured in a similar way to the military, their respective duties have—and still do—overlap, resulting in police falling in the shadow of the military. This further makes them somewhat unapproachable by the general public, a middle state that translates to its lack of identity.

Coronel Rosa Lema, who currently works as the Commander of the Police Station of Cotahuma, likes to believe that police are an integral part of society. This occupational group has been forced to be a tribe but unlike the dwindling population of indigenous Amazonians, they desire to be integrated into and accepted by society, as an approachable entity as well as a protector. However, they are conceptually isolated both due to public perception and a privation of certain constitutional rights.

Law 101, which outlines the Disciplinary Statutes for the Police, was passed on the 4th of April 2011. Although there are sections of this law which clearly state these cannot contradict constitutional provisions, it goes some way towards separating this group from the laws which bind the rest of the population. In a manifesto, they complain at being unfairly isolated from the rest of the Bolivian workforce. A mutiny held in 2012 had the purpose of demanding higher wages, as well as denouncing this law as unconstitutional; some members of the Police Force believed the law failed to uphold the principle of presuming the innocence of the accused in internal disciplinary proceedings.

The Tribe’s Values

Law 101 stipulates the police force is subject to the principles of honor, ethics, discipline, authority, loyalty, cooperation, responsibility, hierarchy, obedience and professional secrecy. Keen to see how these principles work in practice, I asked some members of the force who, despite resentment, seemed to have internalised the principles outlined in this section of the law.

Honour

Despite years of training leading to meagre wages, many policemen are steadfast and passionate about what they do. According to Lema, a total of 800 new recruits enter the institution each year. To Officer Abraham Felipe Felix, the police are paragons of duty and honourability. Their philosophy, in his own words, is to abide by the law, save the weak, help the sick, and influence the youth. They say they respect the law, and like to believe that the law respects them.

Ethics

Modernization of the institution has changed the requirements to enter the force; no longer is unquestioned political loyalty a criterion, but rather physical aptitude and willingness to serve and protect. Felix said that many are driven by their personal interests, and rather than superiors acting through political motive, they are driven by ethical disposition.

Discipline

'La vida es un poco dura', officer Jaime T. Murga said, explaining why some police are turned into violent creatures. On the inside, they are taught to be rock hard against drug-traffickers and terrorists. The punishment given during training is often drastic and militaristic, and the residuals are sometimes taken from the confines of the school to the household.

Cooperation

Even outside of duty, a policeman constantly identifies with his tribe. 'They don’t just go home and rest. Their lives are not separate', Murga said. Although there is an obvious hierarchical arrangement in the institution, Felix believes that all police are one in the same, bonded like kin by the purpose of public service.

Obedience, Hierarchy, Secrecy

Professional secrecy will hold the obedient policeman’s tongue when he is asked a hard question. Policemen have been indoctrinated to be faithful to their superiors, even if it means not denouncing corruption. Speaking with the individuals, they are all united by this ideal—if they say anything at all it is minimal and in a hushed voice. While this principle of secrecy helps them protect valuable and sensitive information, it can also have the unintended consequence of covering up internal corruption in the police force.

The Police in Society

They claim responsibility for the wellbeing of the community. In the past, the police has been used as a tool to instill fear and enforce discrimination amongst the people, but today the police is identifying with values not commonly associated with them. They now try to work with the community instead of against it. The development of Bolivian Democracy was the enzyme for the current civil nature of the police. According to Bolivian philosopher H.C.F. Mansilla, the ideal of 'Communitarian Police' was conceived in the 1980s. For Lema, the police are in the process of building a communitarian culture, in which the police work directly with the citizens, occupy and fix dangerous areas in communities, and work with government authorities to resolve issues such as gang and domestic violence, as well as drug use. While this may seem like a natural role for the police force to adopt, this hasn’t always been the stance.

'We are often poorly perceived by the public, but we are a necessary evil', Felix tells me, sporting a bulletproof vest, his gun nestled by his side.

'Violence is instinctual, to defend ourselves we can kill if we need to', Felix tells me, explaining that it’s not uncommon for them to use violence before using a verbal approach.

Yet behind this hard facade, it is clear they want to be perceived as human beings. While the police may seem just as militant as their camouflaged counterparts, their purpose is quite the opposite, according to Lema, who explains that while the military is trained to attack, the police swear to defend, especially with this new ideal of communitarian police. Lema holds fast to the idea that policemen are as integral a part of society as anyone else, that police and citizen life are not two different identities.

Unfortunately, the police’s public image is largely negative, and in urgent need of having trust with this institution reinstated. According to a report by the CSIS Americas Program, as of 2012 more than 60% of those interviewed believe the Bolivian Police are involved in criminal activities. If you ask the common passerby about their opinion on Bolivian Police, the first word that often escapes their lips is 'corrupt'.

It can be argued that while the corruption in the police force and Bolivian society are endemic, the current law governing the police doesn’t help. Rather than discouraging corruption it can be seen to shield it. With their freedom to speak their mind being restricted, policemen are separated from the rest of society and denied an opportunity to be honest, opinionated and individual.

The future state of this tribe is unclear. The government, citizens and police know that a society needs, and cannot function without, a police force; former Minister Quintana goes as far as arguing the police serves as the 'only agent of cultural mediation' between the government and the people. It seems clear their quest for rights and an identity is not only the concern of this olive-green tribe, but of the country’s citizens at large. To be a part of this tribe means to embrace both physical and psychological changes and challenges, to surrender oneself to the greater good of the nation despite a lack of appreciation. This identity has been and always will be in constant flux.

From the highlands of Macha to the valleys of Torotoro, fighters from the region come together to celebrate the ceremony known as the ‘Tinku’, which in quechua means ‘encounter’. In this anthology of photographs across time and territory, Bolivian Express documents the changing face of these legendary battles.

HISTORY

Source: Ayer Los Andes, Alain Mesili (forthcoming, 2013)

Over the past 40 years, Tinku has taken place across Northern Potosí, Southern Oruro, and on bordering communities between the departments of Sucre and Potosí. San Pablo de Macha (or simply ‘Macha’) holds claim to being the ‘ground zero’ of Tinku, though other prominent locations are Pocoata, Torotoro, Aymaya, Acasio and San Pedro de Buena Vista.

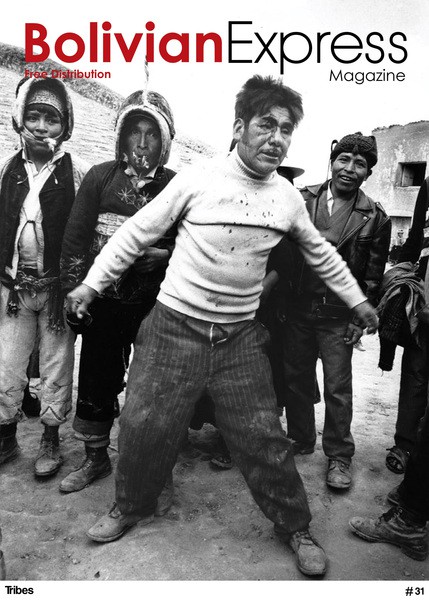

French-born photographer Alain Mesili visited Pocoata in Northern Potosí in 1971, where the Fiesta de la Cruz was to be held on the 3rd of May. To mark this pagan-religious festival, a confluence of indigenous peoples from the surrounding communities meet in the central plaza to fight.

Before the ceremony, the leader of the Tinku carries a large cross on his shoulder into the church. An aguayo can be seen draped over the Christ on the cross, a powerful symbol of the syncretism between ancestral and religious iconography which has become the essence of this tradition. Warriors parade into the plaza, congregating amidst the sounds of hula-hula panpipes and the charango.

Men and women take part in this ritual offering of blood to the Pachamama. ‘The young and old take to centre stage, spitting out teeth in every direction. Bloodstains leave their mark on the arena, and are left there, like trophies [...] after the three days the fiesta takes place, 14 people have died'.

As Alain points out, 'Caiman-brand 90 proof alcohol is the true winner of the ring where the most fierce fights take place [...] from midday onwards, those who don’t fall in combat, are taken down by the chicha'

MACHA: CULTURA VIVA

Photo and text: Carlos Sanchez Navas

The present work documents the celebration of ""Tinku"" (encounter) held in the village of Macha, a community located in the north of Potosi, where every 3rd or 4th of May various Ayllus from Quechua communities prepare for the greatest and oldest fiesta in this region of the country.

This village fiesta, like many in other parts of the country, is characterized by its syncretism. On the one hand, the ‘Lord of the Cross’ is ever present. Each Ayllu displays its own, offering it its faith and devotion, representing Catholic saints and icons. On the other hand, the indigenous world is represented through the participation of the locals. The tribute consists in the blowing of fists between members of different Ayllus, who shed blood. Occasionally this ends in death, and this year was no exception. For them, this practice is a way of giving tribute to the Pachamama, from whom they expect optimal and successful harvest.

A macheño whom I talked to assured that while there is plenty of migration from this region towards neighboring countries, especially among the newer generations, their allegiance towards their culture does not change. It remains in the spirit of every devotee of this great party.

LAIMAS Y PAMPAS

Alexandra Meleán and Caterina Stahl

Two men face each other in a makeshift boxing ring. The crowd presses inward, squeezing tighter. A man cracks a whip at the spectators to maintain space in the ring. Mesmerized spectators casually eat ice cream amidst the violent display. Children enter the ring. Elders test their strength. Over the next few hours, fights are arranged according to relative height, age, and weight: welcome to the Bolivian Fight Club.

A mixture of alcohol, sweat, adrenaline, and testosterone, make for a cocktail of frenzied unconsciousness which culminates with bodies scattered across the pueblo at the end of this 3 day fiesta.

Our Tinku photographs were taken in Torotoro on the corner of Charcas Street, near the Plaza Central. Annually, on July 25, Quechua groups of Laimes and Pampas congregate here, coinciding with the festival of Apostle Santiago.

RUNA TINKU, TOROTORO

Mila Araoz and Amaru Villanueva Rance

At the end of the Tata Santiago four day epic fiesta, Torotoro is scattered with bodies. In what at first appears like population on the verge between life and death, these bodies are rather in a limbo between drunkenness and unconsciousness. If any of them are half-dead, it has nothing to do with fighting. Some have vomit dripping down their shirts whilst others lie on steps and pavements in contorted sleeping positions, as if they had been tortured during their sleep, perhaps whilst dreaming. The streets and houses retain the faint but pungent smell of chicha.

Photo: Mila Araoz

Photo: Amaru Villanueva Rance

Photo: Amaru Villanueva Rance

Photo: Amaru Villanueva Rance

Earlier that day, walking in the midday heat, young children run past and head towards a crowd which gets progressively larger and more dense. Running to join this mass of people my icecream falls onto the dusty dirt road, but it doesn’t matter. We’re barely minutes away from the first fight.

By 11:55am the street is bursting with expectant onlookers. Every balcony and shop window is packed with people, most of them on tiptoes. Some kids have climbed up to a window ledge and grip onto rusty metal fences to get a view of the action. A moustachioed man in the center of this circle uses a belt to whip the spectators in the inner circle to make more space for the fight. Being in the front row suddenly doesn’t seem too attractive.

Up on a friend's shoulders I get the perfect view into this small vortex at the centre of the crowd, where two men prepare for the first fight. For several seconds nothing happens, as the two men in the centre stumble around in inebriation. The eye of the storm is calm and silent. Without warning, the fight begins.

Swinging fists, sweat, screams and tangled bodies. Punches land without aim or grace, it’s all very hard to make out. The fight is broken up after some 20 seconds without a clear victor. Indeed, none is proclaimed. Instead, they greet each other after the fight with a tough embrace. The frenzied men rejoin the crowd with swollen lips and foreheads, blood on their ripped clothes. If they are supposed to be representing their feuding communities, it’s not apparent by their side of the crowd or their clothing. Rather, it seems like a group of young men keen to prove their valour against any worthy opponent. Later they celebrate with a red plastic bucket of chicha. Those who end up unconscious fall to the ground under the influence of alcohol, a mightier opponent to any encountered during the day.

Download

Download