Porque Nada es Imposible Para Dios

Matthew Payton looks at the reality behind the miracle cures offered by Bolivia’s burgeoning evangelical movements

Evangelical churches in La Paz do not exactly promise a home visit from the local pastor, a place in heaven, or a seat on the flower-arranging committee. They offer miracle solutions to problems varying in magnitude from arthritic feet and terminal cancer to financial instability.

While these organisations are, according to their rhetoric, open to the general public, getting an insight into their practices is more complicated than it may first seem. These churches have a paradoxical relationship with the press, on the one hand owning large media corporations spanning radio, print, television and online channels, yet on the other hand being all but closed off to inquisitive journalists such as myself. Years of unfavourable media attention, political disputes between factions, and the large sums of money they mobilise, have turned these churches into organisations which are at once attention hungry and media shy.

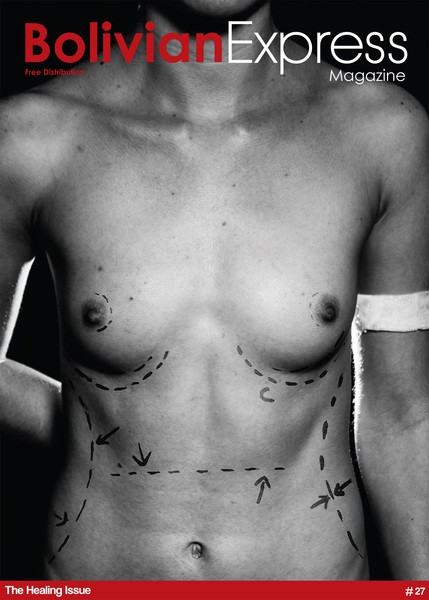

Photo: Katie Rogerson

Getting In

As a first attempt, I try to enter the ‘Pare de Sufrir’ church a few blocks from Plaza Murillo. My first impression of the edifice didn't correspond with my mental image of what a church is supposed to look like: instead of finding myself in front of a neo-gothic building with decorative flourishes, I find myself in front of a businesslike facade made up of grey marble, glass doors and spotless brass features. Upon entering the atrium I am met by two besuited security guards and a receptionist, none of whom are interested in satisfying my curiosity.

After further failed attempts I approach another similar church, the grandiloquently named ‘Ministerio del Nuevo Pacto Poder de Dios’ (Church of the New Covenant and the Power of God). This church, commonly known as ‘Poder de Dios’, owns a radio and TV channel, and has even launched its own political party, 'Concertación Nacional', filling the stadium Hernando Siles and the Plaza San Francisco during the rallies of their heyday. While its fortunes have receded somewhat in the last few years, it remains the largest evangelical church in Bolivia.

The Devout

I am put in contact with Roberto, a member of the congregation, whom I eventually meet after navigating my way through the labyrinthine passageways known as 'Mercado Uruguay'. On finding my Livingstone, we settle in an intimate alcove of a small juice stand, the walls of which are covered in sooty posters of football players, wildlife scenes and colourful devotionals of Jesus Christ.

Roberto, a 55 year-old Paceño with a hardened lined face, scrapes his living as one of the several thousand traders who buy and sell their wares in this mercantile quarter. Upon being asked how long he had been a member of Poder de Dios, he replied instantly that he has ‘always followed Christ’. On my tentative insistence he explained that he has been attending the church for the last four years after an introduction by his wife, who’s been a part of Poder de Dios for the past twelve.

Roberto attends the flagship Poder de Dios megachurch, 'El Monumento a la Fé, Casa de Dios, Puerta del Cielo' once a week on Sundays. Thought visited once a week, Roberto follows Poder de Dios' precepts ‘all days’. He informed me that ‘around 15,000 people attend the first session’, a fact corroborated by several estimates that up to 40,000 worshippers pass through the temple throughout the rest of the sabbath.

Roberto, himself, has experienced various miraculous recoveries from medical ailments, all of which he attributes to Poder de Dios. He recounted suffering from nosebleeds ‘every evening at 7.30 p.m.’, until his wife prayed and ‘handed him to God, Instantly curing him’. His wife, similarly, suffered from pneumonia a few years ago until he prayed at church and was able to witness the disease leave her body. She has been clear of it ever since. When asked whether he considered going to a doctor for his ailments, he explained that his body reacted badly to anaesthesia, adding that he was once hit by a doctor as a boy, leading to his rejection of the medical profession.

Yet his stories, incredibly, are not extreme by the standards of the Poder de Dios website. Featured on this portal are stories of pious members being cured of cancer and arthritis, as well as bizarre cases of people not only being ridden of serious tooth pain, but miraculously appearing with a mouth full of gold-plated teeth. Roberto explains that dentists who were brought in to examine this phenomena, stated that the metal was not used by their profession. Roberto’s conclusion is that the metal must have ‘come from the heavens’ and is therefore ‘supernatural’. Based on such cases, Poder de Dios distributed pamphlets which invite people to 'come and find your miracle'.

The Temple

After speaking to Roberto, it became clear I had to visit 'El Monumento a la Fé' to see for myself. Following my experience at the central branch of Pare de Sufrir, I was all too aware that attempting access using my pigeon Spanish and European visage could pose an issue. However, I was determined; and arrived with a group of friends under the pretense of being teaching volunteers keen to explore our Christian faith away from home. The only information I have on this enormous edifice is the computer generated image I found on their website, as well as the fact that it was built on top of the former factory for Papaya Salvietti, a popular fizzy drink.

The ostentatious 'Monumento a la Fé' has the look of a half-finished sports stadium painted yellow with polarized blue tinted windows. We were quickly ushered into a service held in one of the smaller chambers, where 50-or-so men and women were being dizzied into frenzy by a band playing repetitive and gradually climaxing music. The band was fronted by a tie-and-shirt-wearing pastor who sang and spoke in simplistic devotional phrases with sudden bursts of motion and cadence. The congregation reacted to each crescendo with tears, wails, shrieks, shouts, and even the occasional jumping fit. Cholas, teenage girls and middle class women all clutched tissue ready for the next torrent of tears. When the senior pastor finally took to the podium, he launched into the most staccato, ear piercing and animated recitation of Luke's gospel I have ever heard. The congregates further descended into hysteria with one chola even banging her head on the floor, seemingly out of control.

It is difficult not to feel uneasy enduring suspicious looks from members of the church staff, as well as the wall to wall wailing of our fellow attendees. At one point the preacher nodded to an assistant to bring forth the donations bucket. In a united Pavlovian fit, the entire swaying congregation suddenly halted in their trancelike states to fight to reach the assistant first and donate in their money. To witness congregants being overcome by such desperation to donate money —for impoverished folk any sum is large—was a truly uncomfortable spectacle for a first-world denizen.

While on that day I did not witness any healing miracles, I was able to see the level of power the Poder de Dios Church levies over its members, seemingly premised on a dual mastery of emotive manipulation and show business. The most remarkable discovery of my investigation was the everyday regularity of such holy intervention, part of a worldview in which miracles are not a rare occurrence but rather a phenomenon that can be brought about routinely by following a ritual involving frenzied prayer and large donation, in more or less equal measures.

SUNDAY SERVICE

by Wilmer Machaca

By 6 a.m. around 200 people gather at the ‘Monumento a la Fé’, and more congregants gradually arrive from every corner of the city, El Alto, and even remote rural communities. The majority of the attendees are women wearing polleras.

The female preacher and self-proclaimed Prophet Mrs Magneli (the wife of Luis Guachalla, leader of the church) comes onstage. Magneli addresses sceptics, some of whom seem to think that the money donated goes into the pockets of preachers. She denies this claim explaining that the donations are being used to buy a new satellite for the church’s TV station to expand its reach.

A second group comes onstage bringing offerings in the form of large sacks of rice and potatoes. There are two small children, one of whom has leukemia. They pray to the Lord and curse the devil. Magneli marks some worshippers with oil and blows on them. They fall to the ground and tremble. Some of them laugh uncontrollably. A man who came onstage with breathing problems claims he no longer feels anything, and proceeds to run in celebration. Minutes later a woman is carried onto the stage. She is on a bed lifted by four people.

Magneli makes reference to the tithe and its importance, pointing out that this is money that belongs to God. ‘You can fool me but you can’t fool God; he knows how much you earn and therefore knows what 10% of it is. Not giving him this money is theft’. She sends a group of around 50 young men with donation buckets to every corner of the audience to collect the ‘voluntary’ offerings.

There are around 8,000 people at 8:30 in the morning when the leader of the church, the self-proclaimed ‘Apostle’ Luis Guachalla, finally appears onstage. At around 9:00 Guachalla begins his sermon. This is the central moment, and despite the heavy atmosphere caused by the heat and humidity brought about by having thousands of people in an enclosed space, they all stay. He finishes the sermon with an explosive ‘Power of God!’, making the entire audience enter into a cathartic state of mass frenzy. People fall over forward and start trembling on the floor. ‘This is the Holy Spirit acting within you brothers and sisters’.

In the city of La Paz, Andean cosmology has its own conception regarding the treatment of madness.

In the waiting room of la Caja Nacional de Salud (a psychiatric hospital) the clock on the wall shows it is almost 12:50. The secretary who works there saves her files on the computer and turns to a pair of patients seated on the bench. ‘The doctors are busy’, she says. ‘There is a strike and people are marching. I don’t know what time they can see you. Wait, if you like’.

A plain-looking young woman, sporting a heavy pink coat in the heat of the midday sun, bumps into the secretary at the door. She enters and gives a shy greeting in a soft but hurried voice, and covers her face with her greasy hair upon receiving no response from the secretary. She sits down on the bench and disguises the shame of having been ignored by taking out lipstick from her purse and touching up her make-up.

Her name is Raquel and she is 32, though she introduces herself as Valeria and claims to be only 19. She’s been coming to see the psychiatrist for seven years and yet the cold walls of the room still make her uncomfortable. At present, she lives in Cruce Ventilla, on the road to Oruro, and works in a hair salon.

Illustration: Alejandro Archondo Vidaurre

That’s where she had the first symptoms of her mental illness, a condition her neighbours understood as possession by an evil spirit. She hears voices of men that only exist in her head. The male voices usually speak when she wears red clothing, saying that they want to rape her.

‘My yatiri says that there is a mad spirit inside me performing witchcraft’, says Raquel, while looking at the waiting room ceiling. It’s 15:30 by now and she is the only patient still waiting there.

People like Raquel, who endure mental illness, are treated in this psychiatric hospital and yet they often also visit traditional doctors, due to local beliefs regarding madness. In Andean cosmology, these doctors (or wise men) are known as ‘yatiris’ and they are often charged with the task of treating conditions that do not have rational explanations. This, at least, is how Dr. Fernando Cajías de La Vega explains it, adding that in Aymara culture madness is seen as an otherworldly infliction. Only the yatiris, he says, have a way of understanding, treating and curing the illness. People say yatiris were chosen by Aymara gods to do so, making the wise men very busy and well-respected individuals.

Today, people in La Paz continue to seek their advice and assistance. Yatiris acquire their materials from Sagárnaga street, known as ‘The Witches’ Market’, although they often require no more than coca leaves and alcohol for their work. In special cases, during the ch’allas, or the treatment of a sick patient, they visit the home of whom they wish to see. ‘Everything has its price’, says Dr. Cajías.

According to David, a yatiri living in Pucarani, traditional doctors have different abilities. They can diagnose people's past, present and future, and, because of their connection with the gods, they can physically and spiritually cure patients afflicted by either ailments or curses. Many people look to them precisely for these abilities.

According to David, other types of yatiris who are corrupt and ‘diverted by the path of evil’, can also inflict curses on healthy individuals. These doctors are known as laigas and specialize in inflicting pain onto others. They have the ability to bring about madness using people’s bodies as recipients of evil spirits.

Laigas create a link between a person and a curse by using something that pertains to the victim (a piece of clothing, a lock of hair, some type of object, etc). After giving an offering to an evil spirit, the laiga draws it to the recipient’s body, causing abrupt changes in the victim’s behaviour. According to Raquel’s mother, this is precisely what caused her daughter’s madness, after a young man who had been in love with her asked a laiga to cast a spell on her. The young man allegedly offered a piece of Raquel’s red clothing in order to curse her, after which the laiga brought forth a soul which attracts men to the victim, especially when she’s using red clothing.

Raquel believes that an element of mysticism exists in what is happening to her, but she also trusts the psychiatrist she visits regularly. He tells her the voices she hears don’t have a cure, but that she can control them with medicine, therapy, and sustained treatment.

Raquel was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, which, according to Dr. Mario Sánchez, is an illness that causes emotional problems on top of hallucinations. ‘A lack of emotion is brought about, one doesn’t react emotionally’, explains Sánchez. The family suffers a great deal, as does the affected individual, who becomes depressed and loses willpower.

Although she is constantly touching-up the color of her lips, one can see Raquel’s lack of motivation in her personal neglect. She looks at herself in the mirror, holding it with rough hands that reveal her chewed up fingernails. The dirt underneath them mixes with residues of the red nail polish she put on several weeks ago. Her long hair, put up in a ponytail, reveals the accumulated dirtiness of her scalp and the faded, split ends that fall softly down her back. The pain and the suffering that she endures in her heart is present in her vacant gaze, fixed on the mosaic floor in front of the doctor’s door.

The medications help control the hallucinations, Dr. Mario Sánchez explains, but there is no cure for the patient’s depression. ‘The medications leave you without motivation to do anything, like a cat that only wants to sleep’, says Raquel, leaning on the shoulder of a friend she just met in the waiting room. Specialists confirm that patients stop taking medications because of these side effects, as well as the cost and difficulty of obtaining them.

Dr. Mario Sánchez explains that it is common for patients to leave psychiatric hospitals to seek treatment from yatiris, explaining it is pretty common amongst the lower classes. He adds, ‘Maybe the middle class does it too, but they don’t mention it’. When they return to the hospital, they appear to have improved, although many times they return in a deteriorated state or, in the worst cases, they return with bad news.

Sánchez recalls that some time ago he tended to two brothers with schizophrenia who lived in Viacha, ‘the family and the community abandoned them, everyone behaved aggressively towards them. I got the impression that they could have done something to these patients, because all of a sudden they stopped coming to the psychiatrist appointments; one had disappeared and the other, we found out, had died’.

People with mental illnesses are often seen as an evil presence in their community. Since they are perceived as a negative reflection of the social group, the community often forces the family to address the problem with the help of yatiris.

Although in La Paz schizophrenics turn to yatiris unbeknownst to their doctors, in Cochabamba, these patients engage in rituals with their yatiris inside the hospital. In the Corazón de Jesús Hospital, for example, traditional doctors come from afar and use incense, cleansings and offerings to the gods to ensure the mentally ill are well tended to.

‘In Tarija, the “crazies” walk the streets’, Dr. Sánchez says. ‘They are given work, and violence against them is rare. They are poor people, deep in their own world’.

Psychiatrists indicate that 80% of schizophrenics recover, but that the remaining 20% are incapable of continuing their daily lives and are institutionalized, in some cases for life. On top of this reality, the World Psychiatric Association claims that 83% of the global population doesn’t know what schizophrenia is. The Aymara, whose cultural background provides a different understanding of this type of madness, most likely fall in this category: they can’t be said to know what schizophrenia is.

Raquel grabs her belongings and a man in a white coat hurriedly enters the room. Ignoring her greeting, he enters his office and closes the door. Raquel stops abruptly and is crowded against other patients trying to enter before her. The clock in the waiting room shows 16:50.

Text translated to English by Alan Pierce

Self-medication remains one of the most affordable and widely-used forms of healthcare in Bolivia. Rob Noyes explores the dangers that lurk behind the convenience.

On the steep inclines of the city, littered amongst the shoe-shiners and salteñas, lies a smattering of farmacias, small chemists typically staffed by one or two people in white coats. Their sheer quantity highlights their importance among the Bolivian population’s healing alternatives.

And there are alternatives in Bolivia; concurrently to modern medicine Bolivians have the option to see traditional doctors, or even attend a service at their local evangelist church for a miracle cure.

Alternatively, they may opt to self-medicate: known in medical circles as autoatención. This includes self-prescribing, or asking friends or family for health-related advice and then obtaining the requisite medicine at the pharmacy.

Depending on the cultural and religious background of the family, they may choose different combinations of the choices presented above. However, according to Dr. Ramírez Hita, a social anthropologist, autoatención is the most commonly followed form of healthcare in Bolivia and relies primarily on the women who are at the centre of this self-care system. The mother diagnoses what type of condition the children or husband is suffering and how to cure it.

Self-care is particularly common in the rural areas where few people go to medical centres. Dr. Ramírez Hita attributes this to the poor medical infrastructure, the low quality of the treatments provided by the personnel, and the little confidence the local population has in the medical system.

More generally, the popularity of autoatención appears to be largely due to cost and convenience. Asking friends and family for medical advice is free, going to a doctor for a consultation is not.

Ximena Bastos, whom we spoke to for the article on homeopathy told us: ‘Pharmacies give you what they have, not necessarily what you need. It could be medicine that is too strong for what your symptoms are, or something too weak, or even unrelated’.

Eager to learn about the practices of the pharmacies themselves first hand, I headed to the first one I could find and spoke to the small man drinking his coffee behind the counter. He told me that the Bolivians were ‘generally pretty health conscious people’, and that as such the pharmacies were phenomenally popular. They are cheaper than doctors as well as being quicker. Yet he stressed that they can only do so much – anything bought in a pharmacy must be used in accordance with medicinal advice.

For example, in the winter, the Bolivian Health Ministry provides flu shots to protect the population during the harsher months. Yet as flu is a highly variable virus, and antibiotics do not cure influenza, pharmacists will regularly recommend taking the plant Echinacea in order to boost your immune system. Following this advice, Bolivians will flock to the pharmacies to buy this plant to help them stay healthy over the winter months.

During this course of our conversation with the kind man behind the counter, I carefully watched two customers doing what they do. The first, an elderly gentleman, strolled in and

began to relay a story of how he had been struggling to sleep over the last few nights – an innocuous tale. Surely Night Nurse and maybe some chamomile tea will do the trick? No. The pharmacist pulled out the Valium.

Valium is a highly powerful sedative from the benzodiazepine family. It is not available as an over the counter drug normally, as it can be addictive. Furthermore, half of the drug will still be in your system as long as 90 hours after consumption. Large doses can cause blurred vision, slurred speech and impaired thinking; an overdose can result in death.

Struck by the banality of the scene I am inclined to agree with Ximena– ‘pharmacies give what they have, not necessarily what you need’. Surely this was a sign of malpractice by the pharmacy itself? No, said Ximena. Unfortunately, ‘this speaks more of the poor infrastructure of medicine than of any incompetent pharmacists’.

Until other medical alternatives become more widely available, it seems like people will continue to get what they want at their local farmacia.

Download

Download