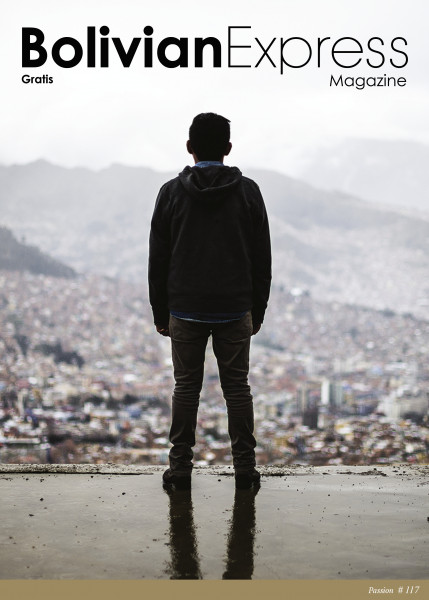

Our cover: Ivan Rodriguez

ENGLISH VERSION :

June was a month of passion. Over the past month, people have been paying close attention to the outcome of the Copa América or if you are of the European persuasion, the Euros. Unfortunately for Bolivia, their run in the Copa America was cut

short as they finished last in their group. Despite recent poor performances at a national level, Bolivia is a country that is

football crazy. I once attended ‘el Classico’, a game between La Paz’s two most successful teams, Bolivar and The Strongest. It is a game that will forever stay with me as songs were belted, drums echoed throughout the stands and even, at one point,

a section of the stadium was host to a small fire started by a group of supporters. Luckily, the fire brigade was on hand to

put it out before it got out of hand. It was clear to me at the time that Bolivia was serious about football and if any country

deserved to see its national team perform at the World Cup, it would be Bolivia.

From a social justice point of view, June was pride month. People across the world furthered the dialogue that is so desperately needed for wider societal acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community. Bolivia is one of very few countries in the world to ban discrimination towards people on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity as written per the

constitution. From a cultural standpoint, the LGBTQ+ peoples within pre-Colombian South America were documented to

be widely accepted. This had changed with the arrival of Catholicism in South America and the process of reversing these sentiments has only recently begun. In December 2020, a court ruling in favour of a civil union between a same-sex couple, David Aruquipa Pérez and Guido Montaño Durán, was met with praise from LGBTQ+ groups in the country. This was

a massive step for the community within the country but this is yet another step in a fight for broader acceptance within the

country. Going back to football but keeping in the spirit of pride month, it is important to note a recent incident at the 2021 Euros. In a game between Germany and Hungary, UEFA had banned the Allianz Arena in Germany from displaying rainbow colours. It sparked a debate among football fans, some stating that football shouldn’t involve politics. LGBTQ+ and trans rights aren’t a political issue but a moral absolute, the notion that pride and football must remain separate is a sentiment I will never understand. Football is a platform in which people express who they are, where they come from and why they are proud of that.

Over the past year, with games played behind closed doors we’ve come to realise that football is nothing without passion, it is nothing without the fans and that is irrespective of whether

you are gay or straight, cis or trans. In this month’s edition of the Bolivian Express, we are celebrating the beautiful game in the spirit of the Copa America and the Euros. We want to tap into what makes the game in the country so special. Additionally, we dive into the world of the ever-present sport of football, we celebrate pride in solidarity of the LGBTQ+ in Bolivia. Happy belated pride month from all of us at the Bolivian Express.

---------------------

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL

Junio fue un mes de pasión y orgullo. Durante el último mes, la gente ha estado muy atenta a los resultados de la Copa América o, la Eurocopa, si te gusta el campeonato europeo. Desafortunadamente para Bolivia, su carrera en la Copa América se vio truncada terminando último en su grupo. A pesar de estos malos resultados de la selección, Bolivia es un país fanático

por el fútbol. Asistí una vez a “el Clásico”, un partido entre los equipos más importantes de La Paz, Bolívar y The Strongest.

Este partido quedará para siempre en mi memoria, recuerdo que mientras se entonaban cánticos de aliento, los tambores

resonaban en las graderías, incluso, en cierto momento, en una parte del estadio se generó un pequeño incendio iniciado

por un grupo de hinchas, por suerte los bomberos lograron apagarlo en cuestión de segundos. Para mí, en ese momento,

quedaba claro en que en Bolivia se tomaba muy en serio el fútbol y si algún país merecía ver a su selección nacional actuar

en la Copa del Mundo, ese sería Bolivia. Desde el punto de vista de la justicia social, junio fue el mes del orgullo, ya que personas de todo el mundo se manifestaron sobre la necesidad de diálogos para una aceptación social más amplia de la comunidad LGBTQ +. Bolivia es uno de los pocos países del mundo que prohíbe la discriminación hacia las personas por motivos de su orientación sexual e identidad de género, establecido en la constitución.

Desde un punto de vista cultural, se evidenció que los pueblos LGBTQ + eran ampliamente aceptados en la América del Sur precolombina. Esto cambió con la llegada del catolicismo a América del Sur y que solo recién ha comenzado a cambiar. En diciembre de 2020,un fallo judicial a favor de una unión civil entre una pareja del mismo sexo, David Aruquipa Pérez y Guido Montaño Durán, fue recibido con elogios por grupos LGBTQ + en el país. Este fue un paso enorme para la comunidad dentro del país, aunque muchos dirán que es un paso más en una lucha que no ha terminado.

Volviendo al fútbol, pero manteniendo el espíritu del mesdel orgullo, es importante destacar un incidente reciente en la Eurocopa 2021. En un partido entre Alemania y Hungría,la UEFA había prohibido que el Allianz Arena de Alemania mostrara los colores del arco iris. Se desató un debate entrelos fanáticos del fútbol, algunos señalando que el fútbol no debería involucrar a la política. Los derechos del colectivo LGBTQ+ y de los transexuales no son una cuestión política,sino un absoluto moral en mis libros, el sentimiento de que el orgullo y el fútbol deben permanecer separados es un sentimiento que nunca entenderé. El fútbol es una plataforma en el cual la gente expresa quiénes son, de dónde vienen y porqué están orgullosos de ello. Durante el año pasado, con los partidos jugados a puerta cerrada, nos hemos dado cuentade que el fútbol no es nada sin el entusiasmo, no es nada sinlos aficionados y eso independientemente de si eres gay o heterosexual, cis o trans.

En la edición de este mes de Bolivian Express, celebramos el deporte rey con el espíritu de la Copa América y la Eurocopa.

Queremos aprovechar lo que hace que el juego en el país sea tan especial. Además de sumergirnos en el mundo del

siempre presente deporte del fútbol, celebramos el orgullo y la solidaridad de la comunidad LGBTQ + en Bolivia.

Feliz mes del orgullo atrasado de parte de todos nosotros en Bolivian Express.

ENGLISH VERSION

Today, South America produces some of the best football players in the world. Such is its footballing success that Joseph ‘Sepp’ Blatter, FIFA’s president, pointed to South America as the ‘Old Continent’ of football. In Bolivia, however, professional football finds itself at a significantly lower level than in many other South American countries. Is there any particular reason for this? Given that Bolivians play as much football as their neighbours, where have they gone wrong?

British expansion in South America during the 19th century brought football to the continent alongside the railways. From the 1870s onwards, British railway construction employees would play football after work. Historically, railways have been a failure in Bolivia; today most trains are out of service. Nonetheless, the tracks themselves remain anchored to the ground. Football, similarly, has become rooted in Bolivian tradition and, although it cannot be dismissed as a failure, its development has been plagued with difficulties.

Football first gained popularity in South America in Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, and Chile, where British presence was most significant. The early-20th-century Argentinian journalist Juan José Soiza Reilly remembered observing a group of fair-skinned men kicking a ball around in the suburbs of Buenos Aires. He asked his father who they were, to which he answered, ‘Crazy English people’.

Bolivia’s Claustrophobia:

Bolivia, a landlocked country surrounded by mountains, took longer to adopt this sport. The country’s geography has been a setback for the development of many activities, and football is no exception. The British presence in Bolivia was far more limited than in other countries, mainly centred around the country’s mining regions, which affected the development of Bolivian football.

The iconic Latin American chronicler Eduardo Galeano talks about the English influence in Argentinean football in Futbol a Sol y Sombra. He notes that a football player could be forgiven for committing a foul only if he was able to excuse himself in ‘proper English and with sincere feelings’. Argentines knew and played football according to the professional rules of the time, but this was not the case in Bolivia. The absence of British presence meant that rules were improvised in many circumstances and, in most cases, Bolivians would opt to invent their own. Even today, Bolivian professional football has some variables that aren’t always consistent with standards around the rest of the world. For example, a few years ago, Bolivia had the youngest player in the National League, making his debut at the age of 12.

Professionalisation:

The professionalisation of football came late to Bolivia. Compared to its neighbouring countries, Bolivia often struggled to keep pace. Argentina founded the Argentine Football Association League (in which the members would communicate exclusively in English) in 1893, while Bolivia established its own league in 1925, more than 30 years later. And while Brazil had already witnessed official football matches between the British Gas Company and the São Paulo Railway, in 1895, Bolivia did not even have a team — its first, Oruro Royal, was founded in 1896. Indeed, Bolivian football remained at an amateur level until the mid-20th century. Today, there is an underground football league, whose members, known as los Siete Ligas, are very skilful players but are unable to break into professional football.

Bolivian Society:

Mario Murillo, a sociologist specialising in Bolivian football, argues that a white elite has always run the game. This social class, according to Murillo, would discriminate against players for their surname and skin colour. Even though there were excellent players of Aymara and Quechua ethnicities, they were not even considered by the professional league. This colonial racism is no longer so prevalent today (although it remains entrenched, to a certain extent), but it has stunted the development of professional football.

Back in 1904, a club was founded in La Paz—The Thunders—composed of young men from the upper classes of the city. All of its members had the opportunity to study in Europe, where football was widely played. The Thunders were the pioneers of football in La Paz, and, due to their social background, it was seen as an upper-class sport. The Strongest, another paceño club, was also founded on similar grounds that allowed for no social integration; it consisted of a group of middle-class friends who had recently finished military service. This tended to hinder the spread of football to other social classes and small communities throughout Bolivia.

Is There a Future for Bolivian Football?

The future of Bolivian football relies on a crucial combination of advanced infrastructure and a passion for the game. In Bolivia, a significant lack of the former means that football is not taken as seriously as it could be. For Bolivia to transform into a successful footballing nation, both elements must coexist.

Watching a Siete Ligas match, one is struck by the paradox between the intense emotional involvement and the distinct lack of appropriate infrastructure. In El Tejar, a region in the north of La Paz, a match was played on a cramped, uneven surface with holes in the nets—almost comparable to a children’s playground. However, with a scoreboard, shirt sponsors, a pedantic referee who gave out yellow cards for incorrect shoes, halftime team talks from gesticulating coaches, and a crowd of at least 150 spectators perched on crumbled-down walls, passion for grassroots football is alive and well. Rather, it is the absence of professional funding that is holding Bolivian football back. Similar to how certain clubs are paralysed in Liga Nacional B for not meeting stadium requirements, Bolivia cannot progress into the top league because its infrastructure is unable to match the levels of involvement and interest.

The ex–Brazilian manager Carlos Alberto Parreira noted: ‘Today’s football demands magic and dreams, but it will only be effective when combined with technique and efficiency’. Solutions could start with a greater distribution of football academies covering the more remote areas of the country that would teach the tactical basics of the game. A structured network of scouts could be employed to recognise and nurture talent from a young age. Moreover, gym training and nutritional advice have become increasingly vital to a player’s physical development and must be valued. These factors helped lead Argentina to excel in the sport, so why shouldn't this be the case with Bolivia?

---------------------

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL

Hoy en día, Sudamérica produce algunos de los mejores jugadores de fútbol del mundo. Tal es su éxito futbolístico que Joseph ""Sepp"" Blatter, presidente de la FIFA, señaló a Sudamérica como el ""Viejo Continente"" del fútbol. En Bolivia, sin embargo, el fútbol profesional se encuentra en un nivel significativamente inferior al de muchos otros países sudamericanos. ¿Hay alguna razón en particular para esto? Dado que los bolivianos juegan tanto al fútbol como sus vecinos, ¿en qué se han equivocado?

La expansión británica en Sudamérica durante el siglo XIX llevó el fútbol al continente junto con los ferrocarriles. A partir de la década de 1870, los empleados británicos de la construcción de ferrocarriles jugaban al fútbol después del trabajo. Históricamente, el ferrocarril ha sido un fracaso en Bolivia; hoy la mayoría de los trenes están fuera de servicio. Sin embargo, las vías siguen ancladas al suelo. El fútbol, igualmente, se ha arraigado en la tradición boliviana y, aunque no se puede tachar de fracaso, su desarrollo ha estado plagado de dificultades.

El fútbol ganó popularidad por primera vez en Sudamérica en Brasil, Uruguay, Argentina y Chile, donde la presencia británica era más significativa. El periodista argentino de principios del siglo XX Juan José Soiza Reilly recordaba haber observado a un grupo de hombres de piel clara dando patadas a un balón en los suburbios de Buenos Aires. Preguntó a su padre quiénes eran, a lo que éste respondió: ""Locos ingleses"".

Claustrofobia de Bolivia:

Bolivia, un país sin salida al mar y rodeado de montañas, tardó más en adoptar este deporte. La geografía del país ha sido un obstáculo para el desarrollo de muchas actividades, y el fútbol no es una excepción. La presencia británica en Bolivia fue mucho más limitada que en otros países, centrándose principalmente en las regiones mineras del país, lo que afectó al desarrollo del fútbol boliviano.

El emblemático cronista latinoamericano Eduardo Galeano habla de la influencia inglesa en el fútbol argentino en Fútbol a Sol y Sombra. Señala que un futbolista podía ser perdonado por cometer una falta sólo si era capaz de excusarse en ""un inglés correcto y con sentimientos sinceros"". Los argentinos conocían y jugaban al fútbol según las reglas profesionales de la época, pero no era así en Bolivia. La ausencia de presencia británica hizo que las reglas se improvisaran en muchas circunstancias y, en la mayoría de los casos, los bolivianos optaran por inventar las suyas propias. Incluso hoy en día, el fútbol profesional boliviano tiene algunas variables que no siempre coinciden con las normas del resto del mundo. Por ejemplo, hace unos años, Bolivia tenía el jugador más joven de la Liga Nacional, que debutaba con 12 años.

Profesionalización:

La profesionalización del fútbol llegó tarde a Bolivia. En comparación con sus países vecinos, a Bolivia le costó seguir el ritmo. Argentina fundó la Liga de la Asociación Argentina de Fútbol (en la que los miembros se comunicaban exclusivamente en inglés) en 1893, mientras que Bolivia estableció su propia liga en 1925, más de 30 años después. Y mientras que en Brasil ya se habían disputado partidos oficiales de fútbol entre la Compañía Británica de Gas y el Ferrocarril de São Paulo, en 1895, Bolivia ni siquiera contaba con un equipo: el primero, el Oruro Royal, se fundó en 1896. De hecho, el fútbol boliviano se mantuvo a nivel amateur hasta mediados del siglo XX. En la actualidad, existe una liga de fútbol barrial, cuyos miembros, conocidos como los Siete Ligas, son jugadores muy hábiles pero no consiguen llegar al fútbol profesional.

Sociedad Boliviana:

Mario Murillo, sociólogo especializado en el fútbol boliviano, sostiene que una élite blanca siempre ha dirigido el fútbol. Esta clase social, según Murillo, discriminaba a los jugadores por su apellido y color de piel. Aunque había excelentes jugadores de etnia aymara y quechua, ni siquiera eran tenidos en cuenta por la liga profesional. Este racismo colonial ya no es tan frecuente hoy en día (aunque sigue arraigado, hasta cierto punto), pero ha frenado el desarrollo del fútbol profesional.

Ya en 1904 se fundó en La Paz un club -Los Truenos- compuesto por jóvenes de las clases altas de la ciudad. Todos sus miembros habían tenido la oportunidad de estudiar en Europa, donde se practicaba mucho el fútbol. Los Truenos fueron los pioneros del fútbol en La Paz y, debido a su origen social, se consideraba un deporte de clase alta. The Strongest, otro club paceño, también se fundó por motivos similares que no permitían la integración social; estaba formado por un grupo de amigos de clase media que acababan de terminar el servicio militar. Esto tendía a dificultar la difusión del fútbol a otras clases sociales y a las pequeñas comunidades de toda Bolivia.

¿Hay futuro para el fútbol boliviano?

El futuro del fútbol boliviano depende de una combinación crucial de infraestructura avanzada y pasión por el juego. En Bolivia, la importante carencia de lo primero hace que el fútbol no se tome tan en serio como debería. Para que Bolivia se transforme en una nación futbolística de éxito, ambos elementos deben coexistir.

Al ver un partido de la Siete Ligas, uno se da cuenta de la paradoja entre un intenso compromiso emocional y la clara falta de infraestructuras adecuadas. En El Tejar, una región del norte de La Paz, se jugó un partido en una superficie estrecha y desigual, con agujeros en las redes, casi comparable a un parque infantil. Sin embargo, con un marcador, patrocinadores de camisetas, un árbitro pedante que sacaba tarjetas amarillas por zapatos incorrectos, charlas de equipo en el descanso por parte de los entrenadores que gesticulaban, y una multitud de al menos 150 espectadores encaramados a muros derruidos, la pasión por el fútbol base está viva. Más bien, es la ausencia de financiación profesional lo que frena al fútbol boliviano. Al igual que algunos clubes están paralizados en la Liga Nacional B por no cumplir con los requisitos de los estadios, Bolivia no puede progresar en la primera división porque su infraestructura no está a la altura de los niveles de participación profesional.

El ex seleccionador brasileño Carlos Alberto Parreira señaló: El fútbol de hoy exige magia y sueños, pero sólo será eficaz si se combina con la técnica y la eficacia"". Las soluciones podrían empezar por una mayor distribución de academias de fútbol que cubran las zonas más remotas del país y que enseñen los fundamentos tácticos del juego. Se podría emplear una red estructurada de observadores para reconocer y cultivar el talento desde temprana edad . Además, el entrenamiento en el gimnasio y el asesoramiento nutricional son cada vez más vitales para el desarrollo físico del jugador y deben ser valorados. Estos factores ayudaron a Argentina a sobresalir en este deporte, así que ¿por qué no debería ser el caso de Bolivia?

ENGLISH VERSION

With a series of LGBT+-related events running over the last few weeks in La Paz, I discovered a ‘¿Literatura homosexual en Bolivia?’ panel, and, not knowing much about Bolivian literature, I was intrigued. The idea of a dialogue on whether such literature exists in Bolivia clashed with stereotypical preconceptions I had of the machista culture present in Latin America. The question marks in the title were telling, at least for me, as the questioning of the existence of the literature would seem to imply a questioning of the LGBT+ community in Bolivia, or rather their visibility.

Before the event took place, however, I had an interview with one of the participants, Mónica Velásquez, an award-winning poet and professor of literature at the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés. Velásquez took the conversation from a more literary point of view, claiming that the other people speaking at the event were ‘much more activist.’ We talked about how art and literature can allow someone to avoid reducing their work to their identity, citing one of her favourite poets, Fernando Pesoa, in saying, ‘Poetry invents subjectivities, and because of this you can have many voices.’ An interesting viewpoint, given the event Velásquez was soon to speak at was about a specific identity found in literature. She did, however, tell me, ‘I believe that one of the first functions of the art of these groups we have spoken about is about making them visible; art is a testimonial.’ Velásquez further noted, though, that there was a danger surrounding agendas and ‘pamphlet literature’ or propaganda, that focusing too much on identity could diminish the quality of writing. The literature student in me tended to agree; the would-be activist was not so sure.

I headed to the event itself the next day, where Rosario Aquím, Lourdes Reynaga, Virginia Ayllon and Mónica Velásquez were speaking. The four analysed the presence of LGBT+ authors, characters and narratives in the canon and debated the merits of intermingling activism and literature. The event was quite popular, with people crowding a small room at the Centro Cultural de España, which fittingly appeared to be a kind of library. The evening culminated in a brief interview with the organiser of the event, Edgar Soliz Guzmán, also a poet. When asked why the conversatorio was important to have now, he told me that government legislation hasn’t solved enough of the problems faced by members of the LGBT+ community. ‘There is a sort of invisibility that exists in the canon and society,’ said Soliz Guzmán.

Our conversation ended on the point that identity is in art but does not constitute it, which suggests to me that who you are seeps into what you do, but doesn’t necessarily have to define it. Soliz Guzmán said, ‘Literature isn’t written to justify existence.’ But it seems to me that the mere act of writing and looking for this literature helps to make the community visible and to normalise it. I agree, literature should not have to justify existence, but then nothing should have to justify existence. If art really is testimonial, then existence is implied.

-----------------

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL

Con una serie de eventos relacionados con el colectivo LGBT+ que se están celebrando en las últimas semanas en La Paz, descubrí una mesa redonda titulada ""¿Literatura homosexual en Bolivia?"" y, sin saber mucho sobre la literatura boliviana, me quedé intrigada. La idea de dialogar sobre la existencia de este tipo de literatura en Bolivia chocaba con las ideas estereotipadas que tenía de la cultura machista presente en América Latina. Los signos de interrogación en el título eran reveladores, al menos para mí, ya que el cuestionamiento de la existencia de la literatura parecería implicar un cuestionamiento de la comunidad LGBT+ en Bolivia, o más bien de su visibilidad.

Sin embargo, antes de que se celebrara el acto, tuve una entrevista con una de las participantes, Mónica Velásquez, poeta premiada y profesora de literatura en la Universidad Mayor de San Andrés. Velásquez tomó la conversación desde un punto de vista más literario, afirmando que las otras personas que hablaron en el evento eran ""mucho más activistas"". Hablamos de cómo el arte y la literatura pueden permitir que alguien no reduzca su trabajo a su identidad, citando a uno de sus poetas favoritos, Fernando Pesoa, al decir: ""La poesía inventa subjetividades, y por eso puedes tener muchas voces"". Un punto de vista interesante, dado que el evento en el que Velásquez iba a intervenir próximamente versaba sobre una identidad específica que se encuentra en la literatura. Sin embargo, me dijo: ""Creo que una de las primeras funciones del arte de estos grupos de los que hemos hablado es hacerlos visibles; el arte es un testimonio"". Sin embargo, Velásquez también señaló que existía el peligro de las agendas y de la ""literatura panfletaria"" o propagandística, y que centrarse demasiado en la identidad podría disminuir la calidad de la escritura. El estudiante de literatura que había en mí estaba de acuerdo; el aspirante a activista no estaba tan seguro.

Al día siguiente me dirigí al evento propiamente dicho, en el que intervenían Rosario Aquím, Lourdes Reynaga, Virginia Ayllon y Mónica Velásquez. Las cuatro analizaron la presencia de autores, personajes y narrativas en el canon LGBT+ y debatieron sobre las ventajas de mezclar el activismo y la literatura. El acto fue bastante concurrido, y la gente abarrotó una pequeña sala del Centro Cultural de España, que parecía una especie de biblioteca. La velada culminó con una breve entrevista al organizador del evento, Edgar Soliz Guzmán, también poeta. Cuando le pregunté por qué era importante celebrar el conversatorio ahora, me dijo que la legislación gubernamental no ha resuelto suficientemente los problemas a los que se enfrentan los miembros de la comunidad LGBT+. Hay una especie de invisibilidad que existe en el conjunto de normas y en la sociedad"", dijo Soliz Guzmán.

Nuestra conversación concluyó en el punto de que la identidad está en el arte, pero no lo constituye, lo que me sugiere que, quién eres se filtra en lo que haces, pero no tiene por qué definirlo. Soliz Guzmán dijo: ""La literatura no se escribe para justificar la existencia"". Pero me parece que el mero hecho de escribir y buscar esta literatura ayuda a visibilizar la comunidad y a normalizarla. Estoy de acuerdo, la literatura no debería tener que justificar la existencia, pero entonces nada debería justificar la existencia. Si el arte es realmente testimonial, entonces la existencia está implícita

Photos: Alexis King

ENGLISH VERSION

Sat in Don Massimo’s office, the walls of which are adorned with photos and trophies from various football teams he’s helped, he tells a story of when he first established a football school in Cochabamba. He recalls that the first obstacle was to win the trust of the locals who weren’t convinced: ‘Who does this Italian think, he is coming here and claiming he can teach our kids how to play football.’ But over two decades later, Massimo Casari and his wife Verónica Urquidi have become incredibly influential members of the local community. Since 1996, they have set up various projects through their main foundation, Fundación Casari, aimed at helping disadvantaged families and children in difficult situations across Cochabamba.

Don Massimo, as he is affectionately referred to by the children and parents alike, is originally from Bergamo in Italy. He first came to Cochabamba in 1986 with an Italian charity that helped children in need. Returning every year thereafter, he would pay for his trips by selling any type of car he could. In 1994, Don Massimo met Verónica, and moved to Bolivia permanently after getting married in 1995. After spending three years running a house for children, in 2000 the couple decided to build a recreational and educational house (Centro Educacional Recreativo, CER) in the barrio of Ticti Norte. Verónica, a cochabambina, has been hugely important in everything they do, providing local knowledge and experience.

The aim of the CER is to provide apoyo escolar, or educational support, for underprivileged children while they are not at school, supporting around 150 students up to the age of 15. Most of the children are from poor or troubled families in the neighbourhood. The centre provides a safe place for them to learn and have fun, through attending homework class and playing football together.

It doesn’t take long talking to Massimo to realise just how important football has been and still is in his life, and something which is at the heart of what he and his wife do to support young people in Cochabamba. The free football school, which was once an important part of the CER, has become a project in itself. While the two initiatives have steadily become less connected, many children still attend both.

Since 2008, Fundación Casari has been working with Inter Campus, the foundation of the Italian football club Inter Milan. As well as helping to fund the CER, the club provides training and pay the coaches’ wages, all of whom come from Cochabamba. Every year, Inter Campus also provides 220 uniforms for the children, which cost over 80 euros a piece in Europe, as Massimo proudly points out.

On weekdays, morning and afternoon, children are able to go along to the football school without having to pay a cent. Watching a training session was an impressive and somewhat surreal sight, to see the mass of navy and black Inter Milan shirts in a quiet neighbourhood of the city.

Unsurprisingly, Massimo is effusive in his praise for Inter Campus. He fondly recalls how in 2009, the foundation paid for 14 children from the CER under the age of 12, to participate in their ‘Copa del Mondo.’ Even though the majority of the kids had never left Cochabamba, the programme flew them to Florence to spend a week playing football against children from other Inter Campus foundations.

The foundation’s work with Inter Campus has enabled Verónica and Don Massimo to launch other social projects. In Irpa Irpa, about 70 kilometres away from Cochabamba, they set up a centre for children named Jatun Sonqo, which means big heart in Quechua. The project involves a similar apoyo escolar, but also works with the mothers of the children, running workshops, such as bakery classes or clothes making. The project partners 160 local families with 160 sponsors in Italy who support the centre.

With the help of Sister Mariana Heles González, Fundación Casari also supports children who live with their mothers in the local prison. Every Saturday morning, around 40 to 50 children are picked up from a nearby prison and taken to the CER to play football and enjoy themselves. The programme, called 'Niños Fuori', which means 'Children Outside’, in a mix of Spanish and Italian, is completely funded by Inter Campus. For the kids involved, Massimo explains, it gives them a break from the strict life inside the prison and a day of freedom.

As if that were not enough, Foundation Casari also helps run a community house for people with a variety of mental and physical disabilities, funded by his friends back in Italy. Every evening Massimo and Verónica have dinner at the house.

What is perhaps most amazing is to see Massimo and Verónica laughing and joking with both the children and their parents. It's easy to see why they are so well-liked in the community.

Talking to the children at the CER, they talk about feeling happy and making friends. When we asked what they like most about the centre, they unanimously replied: 'Doing homework!'. Perhaps a little surprising, but it’s clear nonetheless how important it has been for them to have a fun and safe place to come and learn.

We spoke to one parent whose child attended the football school, to ask about the influence of the foundation’s work. 'Apart from doing physical exercise,’ he said, ‘as a way of distracting themselves and having fun, some kids have become more independent.' When asked what he thought of Don Massimo, ‘muy buena gente.’ was the simple response.

The close bonds he and Verónica have developed with the children, which he describes as 'como sus hijos', have meant they have become almost parental figures for some. Being so close with the children brings a real responsibility, however, something Massimo is very aware of. He mentions times when children have confided their most serious problems in him, including instances of domestic violence, or young girls experiencing the inevitable challenges of puberty.

When a former hijo comes back, it is always special for Massimo. He fondly recalls the example of a young boy that recently came back after many years with his wife and son; or a young girl who is now a qualified vet and others who are now doctors, policemen and footballers.

Through the amazing work of Massimo and Verónica, Fundación Casari has truly changed the lives of thousands of children across Cochabamba.

For more information, visit http://www.comitatocasari.org/.

-------------------------

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL

Sentado en la oficina de Don Massimo, cuyas paredes están adornadas con fotos y trofeos de varios equipos de fútbol a los que ha ayudado, cuenta la historia de cuando fundó una escuela de fútbol en Cochabamba. Recuerda que el primer obstáculo fue ganarse la confianza de los lugareños que no estaban convencidos: ""Quién se cree este italiano que viene aquí y dice que puede enseñar a nuestros niños a jugar al fútbol”. Pero más de dos décadas después, Massimo Casari y su esposa Verónica Urquidi se han convertido en miembros increíblemente influyentes de la comunidad local. Desde 1996, han puesto en marcha varios proyectos a través de su principal fundación , la Fundación Casari, destinados a ayudar a familias desfavorecidas y niños en situaciones difíciles en Cochabamba.

Don Massimo, como lo llaman cariñosamente los niños y los padres, es originario de Bérgamo en Italia. Llegó por primera vez a Cochabamba en 1986 con una organización benéfica italiana que ayudaba a niños necesitados. A partir de entonces, volvía cada año y pagaba sus viajes vendiendo cualquier tipo de coche que obtuviera. En 1994, Don Massimo conoció a Verónica, y se trasladó a Bolivia definitivamente tras casarse en 1995. Después de pasar tres años dirigiendo una casa para niños, en 2000 la pareja decidió construir una casa recreativa y educativa (Centro Educacional Recreativo, CER) en el barrio de Ticti Norte. Verónica, una cochabambina, ha sido enormemente importante en todo lo que hacen, aportando conocimiento y experiencia local.

El objetivo del CER es proporcionar apoyo escolar a los niños desfavorecidos mientras no están en la escuela, apoyando a unos 150 estudiantes hasta la edad de 15 años. La mayoría de los niños provienen de familias pobres o con problemas en el barrio.. El centro les proporciona un lugar seguro para aprender y divertirse, asistiendo a clases de los deberes escolares y jugando al fútbol juntos.

No hace falta hablar con Massimo para darse cuenta de lo importante que ha sido y sigue siendo el fútbol en su vida, y algo que está en el corazón de lo que él y su esposa hacen para apoyar a los jóvenes en Cochabamba. La escuela de fútbol gratuita, que antes era una parte importante del CER, se ha convertido en un proyecto aparte. Aunque las dos iniciativas se han ido desvinculando, muchos niños siguen asistiendo a ambas.

Desde 2008, la Fundación Casari ha estado trabajando con Inter Campus, la fundación del club de fútbol italiano Inter de Milán. Además de ayudar a financiar el CER, el club brinda capacitación y paga los salarios de los entrenadores,todos ellos procedentes de Cochabamba. Cada año, el Inter Campus también proporciona 220 uniformes para los niños, que cuestan más de 80 euros la pieza en Europa, como señala Massimo con orgullo.

Entre semana, por la mañana y por la tarde, los niños pueden acudir a la escuela de fútbol sin tener que pagar un céntimo. Ver una sesión de entrenamiento fue un espectáculo impresionante y algo surrealista, al ver la cantidad de camisetas azules y negras del Inter de Milán en un barrio tranquilo de la ciudad.

No es de extrañar que Massimo sea efusivo en sus elogios a Inter Campus. Recuerda con cariño que en 2009 la fundación pagó a 14 niños del CER menores de 12 años para que participaran en su ""Copa del Mondo"". Aunque la mayoría de los niños nunca habían salido de Cochabamba, el programa los llevó en avión a Florencia para que pasaran una semana jugando al fútbol contra niños de otras fundaciones de Inter Campus.

El trabajo de la fundación con Inter Campus ha permitido a Verónica y Don Massimo poner en marcha otros proyectos sociales. En Irpa Irpa, a unos 70 kilómetros de Cochabamba, crearon un centro para niños llamado Jatun Sonqo, que significa corazón grande en quechua. El proyecto implica un apoyo escolar similar, pero también trabaja con las madres de los niños, impartiendo talleres, como clases de panadería o confección de ropa. El proyecto asocia a 160 familias locales con 160 padrinos en Italia que apoyan el centro.

Con la ayuda de la hermana Mariana Heles González, la Fundación Casari también apoya a los niños que viven con sus madres en la prisión local. Todos los sábados por la mañana, entre 40 y 50 niños son recogidos en una prisión cercana y llevados al CER para jugar al fútbol y divertirse. El programa, llamado ""Niños Fuori"", que significa ""Niños fuera"", en una mezcla de español e italiano, está completamente financiado por Inter Campus. Para los niños que participan en él, explica Massimo, supone un descanso de la estricta vida dentro de la cárcel y un día de libertad.

Por si fuera poco, la Fundación Casari también ayuda a gestionar una casa comunitaria para personas con diversas discapacidades mentales y físicas, financiada por sus amigos en Italia. Todas las noches, Massimo y Verónica cenan en la casa.

Lo más sorprendente es ver a Massimo y Verónica riendo y bromeando con los niños y sus padres. Es fácil ver por qué son tan queridos en la comunidad.

Hablando con los niños del CER, hablan de sentirse felices y de hacer amigos. Cuando les preguntamos qué es lo que más les gusta del centro, respondieron unánimemente: ""Hacer los deberes"". Tal vez sea un poco sorprendente, pero está claro, no obstante, lo importante que ha sido para ellos tener un lugar divertido y seguro al que acudir para aprender.

Hablamos con un padre cuyo hijo asistió a la escuela de fútbol, para preguntarle sobre la influencia del trabajo de la fundación. 'Aparte de hacer ejercicio físico', dijo, 'como forma de distraerse y divertirse, algunos niños se han vuelto más independientes'. Cuando se le preguntó qué pensaba de Don Massimo, 'muy buena gente' fue la sencilla respuesta.

Los estrechos lazos que él y Verónica han desarrollado con los niños, que él describe como ""como sus hijos"", han hecho que se conviertan casi en figuras parentales para algunos. Sin embargo, estar tan cerca de los niños conlleva una verdadera responsabilidad, algo de lo que Massimo es muy consciente. Menciona ocasiones en las que los niños le han confiado sus problemas más graves, como casos de violencia doméstica, o chicas jóvenes que experimentan los inevitables desafíos de la pubertad.

Cuando un antiguo hijo regresa, siempre es especial para Massimo. Recuerda con cariño el ejemplo de un joven que volvió hace poco, después de muchos años, con su esposa y su hijo; o el de una joven que ahora es veterinaria titulada y el de otros que ahora son médicos, policías y futbolistas.

Gracias a la increíble labor de Massimo y Verónica, la Fundación Casari ha cambiado realmente la vida de miles de niños en Cochabamba.

Para obtener más información, visite http://www.comitatocasari.org/.

Download

Download