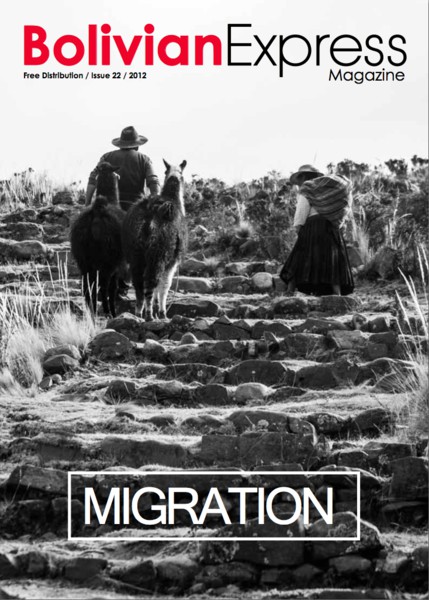

Rural-Urban migration Trajectories in the Bolivian Andes

At 4,150 meters above sea level, towering above the city of La Paz, you’ll find El Alto: a migrant town made up almost entirely of indigenous people; a place tormented by the cold winds of the altiplano, infamous for its high levels of poverty and criminality. Skyrocketing population growth have transformed this former village into the fastest growing city in Bolivia.

The explosive population growth in El Alto is a result of mass migration, a phenomenon that has made Bolivia, once a predominantly rural country, a nation with an urban majority. There are political, historical and environmental reasons for this development, all of which have contributed to the gradual impoverishment of life in rural areas and have made living conditions there increasingly harsh.

Rural migrants hope to earn a higher income, improve their social status and find a better life in the city. The reality of El Alto, however, is quite different. Instead of being a step towards a better and more urban lifestyle, migrants are faced with a lack of services, and employment opportunities are hard to come by. All of this pushes people to find different ways of sustaining their livelihoods.

Historically speaking, migration has been an important feature of life in Andean communities. For thousands of years, migration has been a way of coping with political, economic, and environmental changes. Agricultural systems, for example, used to be based on a model of vertical production, in which products were grown at various altitudes, forcing farmers to move along the landscape according to the seasons.

During the Spanish conquest and subsequent colonisation, there was a radical shift in how agriculture was handled in Bolivia. When the Spanish conquered the land, they distributed it amongst themselves in the form of large haciendas. Following Bolivia ́s independence from Spain in 1825, this system not only remained in place, but was expanded, expelling indigenous communities from their lands and therefore providing further incentive for rural migration.

The most important change, however, which laid a basis for mass rural-urban migration in Bolivia, came about in 1952 with Bolivia’s National Revolution. Two things were especially significant. First, the agrarian land reform, which ignored traditional vertical-based agricultural practices and made farmers less resistant to changes in season and climate. Second, the inclusion of indigenous people as recognised citizens, which opened up new chances for social mobility.

Alongside these developments, there were several other factors that in fluenced migration, such as severe droughts, climate change and the economic crisis of the 1980s, which recorded inflation rates of over 27 percent.

In the long run, these developments led to the formation of towns like El Alto, where the huge influx of migrants overruled the possibility of creating proper facilities, administering basic services and offering jobs that would be needed. This contributed to the increase of poverty and criminality rates, making some of the migrants perhaps even worse off than they would have been in their places of origin.

Rural-urban migration has also had negative consequences on the countryside due to the fact that it has been mostly men who have migrated to the cities, meaning that women are left with double the workload in the countryside.

It would be wrong to say, however, that rural-urban migration is a purely negative phenomenon and that a town like El Alto, with its lack of services and facilities, is only a place of poverty and despair. According to José Luis Rivero Zegarra, general coordinator of CEBIAE, that would only be a ‘capitalist’ way of looking at the place.

There is so much more to El Alto that can be seen if one abandons the ‘Western way of looking’ and embraces other visions. Then, it would be possible to see that El Alto is much more than a place of poverty and criminality. It is also a place for different ways of seeing life; a place made up of different indigenous traditions and systems of morality, mixed with ‘urban and capitalist’ views--a place, that is, for innovation and creativity.

Rural life tends to be reproduced in cities like El Alto due to the deep ties of its inhabitants with the countryside. For them, getting away to the city does not mean leaving their rural community entirely. At times, a migrant is asked to return to the countryside to govern his or her local community. At others, communal ties place moral limits on how much an individual can enrich him or herself in the city. Some people believe that an individual’s fortune results from the support lended to him or her by the community, which is why they have an obligation to let their wealth flow back into the countryside. They may throw a party in the city or in their village in retribution.

This is why José Luis Rivero Zegarra suggests that El Alto’s way of life cannot be fully understood through a capitalistic logic. ‘It is a different way of living’, he says, ‘that responds to cultural traits that have been alive for centuries.’

Despite far reaching attempts to suppress this culture by importing a Western way of life, presented as ‘the right way’ of living, Zegarra says, in past decades ́indigenous and traditional ways of living have gained ground again.’ He goes on: ‘Bolivia is going through an identity crisis, in which people have to ask themselves who they are, what their values are and what place they want to take in the world ́.

In Bolivia’s process of defining its own identity, the concept of being indigenous -once something to be ashamed of- has become something that nobody tries to hide anymore. In light of this, instead of pitying El Alto for its poverty rates and so-called ́backwardness ́, we might take Zegarra’s views as a source of inspiration and begin to experience El Alto as a new way of viewing life, in which the community is placed above the individual, and in which solidarity, reciprocity, and

mutual caring prevail.

Special thanks to: José Luis Rivero Zegarra, CEBIAE (Centro Boliviano De Investigación y Acción Educativas), Fundación Pueblo

A colonial tale of Bolivia’s original migrant population

It is a well-known story. In 1492, the forty-one-year-old Christopher Columbus, a then unknown Genoan sailor, convinced King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain to fund his voyage to discover a western maritime passage to the Far East. With the rich rewards that the ‘Capitulations of Santa Fe’ promised, whereby Columbus would attain the rank of ‘Admiral of the Ocean Seas’ and Viceroy and Governor of any new lands he claimed for Spain, he embarked upon an unprecedented journey. In October, after a journey greatly facilitated by his knowledge of the Atlantic trade winds, Columbus and his crew sighted land. He landed at what is presumed to be the Bahamas - which he christened San Salvador-, and became the first European to ‘discover’ the Americas. Columbus however, maintained that he had not discovered the ‘New World.’ Rather, he had unearthed a new sea-route to an old world, that of the East Indies.

Fast-forward forty years to 1533, and the Spanish conquest of the Inca empire was nearly complete. Present-day Bolivia was known as Alto Perú and was ruled by the Viceroy of Lima. In the first one hundred years of Spanish imperial rule, 250,000 Spaniards migrated to Alto Perú, and would continue to colonize the country for the following 300 years. But who were these Spanish migrants?

The New World was a distant, daring and dangerous prospect. The passage across the Atlantic in wooden ships was harsh and exhausting, and whilst the prospective riches loomed heavy on the horizon, there was no incentive to engage in such a risky pursuit when one had relative stability in Spain. Thus, the well-to-do families tended not to colonise the New World. At the same time, society’s poorest could not afford to make the journey. The crossing was costly, and those peasants stagnating at the bottom of Spain’s social hierarchy were in no position to participate in the creation of the Spanish colonies.

It was a middling and marginalised individual that took the gamble of packing up his existence in Spain and setting out for the great unknown. Poor journeymen and the illegitimate children of impoverished gentry set sail for the New World, not artisan craftsmen and the sons of major landholders. As Herbert Klein acknowledges, ‘it was, in short, the lowest groups within the potentially upwardly mobile classes who left for America.’

Upon arrival, migrating Spaniards discovered a greatly undeveloped continent compared to their native Spain and, for the very first immigrants, a country plagued with militaristic conquest.

The challenge of migrating to the New World was inextricably linked with the promise of riches and exploitation, and the nature of the proceeding conquest was exacted with this in mind. In the absence of Spanish peasants,indigenous peasants formed the bottom tier of the social hierarchy. Without any competing institutions or classes, the migrating Spaniards received an instant elevation from their social position in Spain.

In such unusual circumstances, the establishment of a permanent Spanish society in South America became a reality from the very beginning of the emigration. Regardless of their former status in Spain, their perceived cultural and racial supremacy placed any Spaniard above an indigenous Bolivian. Where once the titles Don and Doña were restricted to the elite, by the second generation of conquistadors they were being more generally applied to all whites.

The migrating Spaniards arrived very much aware that both posterity and God would judge them by their actions in the New World. The first product of this mindset was a fervour for conquest, construction, and religious conversion.

In the early 1540s, the Spanish conquistadors felt confident enough to push south in a bid to extend their rule, and their efforts were met with the rich re- ward they had hoped to attain. Whilst the pursuit for the mythical El Dorado was entirely futile and unfruitful, silver- rich Potosí exceeded the wildest hopes and dreams the Spanish held for the inestimable treasures of the New World. Founded in 1545 as a mining town, Potosí became the most populous city in the Western Hemisphere. By 1600, its population of 150,000 likely exceeded that of London, and Spain was bankrolled throughout the sixteenth and into the seventeenth century by the silver that left the cavernous mouth of the city’s mountain.

The Spanish conviction in their New World activities established a vibrant chronicle tradition, which greatly aids our understanding of the migration. Bartolomé Arzans de Orua y Vela was born to first-generation Spanish parents in 1676 in Potosí, and his epic work chronicles life in the city and elsewhere in Alto Perú.

Despite the immense riches beneath Cerro de Potosí, life in Alto Perú, and particularly in the city of Potosí, was described by Arzans as proving very

challenging for the migrant Spanish residents. The immense altitudes in Bolivia were novel and formidable. At over 4,000m, Potosí greatly exceeds Spain’s highest point, and it made childbirth a real difficulty. Arzans chronicles how a majority of the first children born in Potosí bore the name of Nicolás, a result of desperate Spanish parents naming their firstborn sons after the San Nicolás de Tolentino (the patron saint of difficult births), in a bid to secure a safe delivery.

The wealth a man made in the New World however, and his improvement in social standing, was non-transfera- le. Settlers could not assimilate into the Spanish nobility and rub shoulders with the Iberian gentry should they decide to return to Spain, despite at taining such a standing in Alto Perú. The product of this scenario was the creation of a permanent migrant community from the very beginning.

This societal structure that was crafted in Bolivia in the sixteenth century has remained remarkably intact over half a millennia. The large indigenous population continue to exist at the bottom of the socioeconomic structure, whilst the small elite are of European descent. A 2006 paper by the Oxford Department of International Development (ODID) revealed the extent of horizontal inequality (economic disparity does not stem from any difference in intelligence and skills) in Bolivia, putting into academic writing what is immediately apparent when one spends any amount of time in Bolivia.

More than a third percent of indigenous Bolivians live in ‘extreme poverty’, compared to just 12.8 percent of non-indigenous almost three times greater. Not until the 1952 Revolution could indigenous Bolivians vote or even go near La Paz’s Presidential Palace in Plaza Murillo. Pale-skinned European descended elites continued to rule until Evo Morales was sworn in as president in 2006, which brought the first indigenous Bolivian leader to power in a country with a an indigenous majority.

The same ODID paper cites a survey of Bolivians that revealed that nearly two out of every three Bolivians believe their ethnic or racial origins affect their chance of employment in the private or public sector. Of those who identified as indigenous, 76 percent believed ethnicity had an impact on their working possibilities. The plight of indigenous Bolivians is plain to see and persistent.

Evo Morales established a new constitution in 2009. It gave indigenous peoples unprecedented rights, championing native culture like the coca leaf, making symbolic gestures such as the adoption of the wiphala and more active reforms such as the 2006 redistribution of 77,000 square miles of land to Bolivia’s poor population.

When one wanders the streets of La Paz, however, and sees the cholita stalls and the lustrabotas on every corner, or when one visits El Alto, where the population is 80 percent indigenous in sharp contrast to the European-descended residents one sees on the streets of Zona Sur, or even Sopocachi, the impact of the 500-year- old migratory wave from Spain is quite apparent. It continues to affect politics, social standing, and economic success. Perhaps no other global migration has had such a profound effect as that of Spain’s conquistadors.

Stitching their way across the seams of country borders, Bolivians head south in search of a better future.

With over 1.2 million residents, the largest Bolivian community outside the country is in Buenos Aires. Despite the promises of vast opportunities and dreams of an improved quality of life , the reality can be much different once they arrive. Rose Acton explores how the prospect of living in near-slavery conditions is sometimes less terrifying than the prospect of returning to the country empty-handed.

Buenos Aires is a vast and diverse city, a cosmopolitan metropolis laced with colonial architecture and peppered with downtrodden villas. It attracts a remarkable number of Bolivian migrants, drawn by the bright city lights. Currently around 1.2 million Bolivians live in the Buenos Aires province alone, a further 300 thousand scattered across Argentina, most in search for a better life and increased opportunities.

The flow of Bolivians to Argentina has been a trend for many decades; during the late 1980s and early 1990s, many ex-miners from the valley of Cochabamba travelled to Buenos Aires to work in sewing workshops and other locations. The Argentine economic crisis of 1999–2002 meant that many Bolivian migrants returned home, while others continued their migratory cycle to Spain. Despite Argentina’s economic recovery following the crisis, it has recently begun to suffer stagflation, a term used by economists to describe a mix of stagnant growth and strong inflation.

Amador Choque Ajata first came to Buenos Aires out of curiosity and returned to live there because he missed ‘how big and different things are compared to La Paz—the city is more complete.’ He tells me that the majority of Bolivians are curious to see what things are like in Buenos Aires; they come for the standard of living. They see the opportunities for work, and they are impressed by the transportation and health system. Amador also tells me how many migrants are impressed by different consumer products which aren’t available in La Paz.

Bolivians who arrive in Buenos Aires traditionally work within the textile industry. However, at least for the first year or two, this tends to be illegally – trabajan en negro. This illegal migration status clearly affects migrants’ choices and opportunities, and many Bolivians find themselves working in precarious conditions. The number of people living in near-slavery conditions is estimated at around 500,000 people; half of these are garment workers who live and work in sweatshops. Employers typically pay for the immigrants’ transport from Bolivia, as well as their food for the first few weeks, leaving many trapped: one woman described how she had to work for six months without a check in order to pay back all the money she owed; another man described how he earned $30 in first month, of which his boss kept $26. The threatening behaviour of their employers and a fear of the authorities leaves them with few other choices. Many are also physically trapped, with employers locking the doors and as many as 10 to 12 people living per room. Long working hours are the norm, with some employees expected to stay at their machines from as early as 7 am untilaslateas1amor2am.Ifthemigrants had the necessary legal papers – trabajan en blanco – they would have access to medical and work insurance and would be able to work fewer hours by adopting other occupations as cleaners, receptionists, etc. However, this is rare, as most Bolivian migrants are in irregular situations, severely limiting their options.

The conditions related here form a stark contrast to the initial dream of a better life. Amador portrays how people who arrived 10- 15 years ago had many opportunities, due to the increased purchasing power afforded by the Argentinean peso’s parity with the dollar. Back then, a peso would buy you up to 6 Bolivianos, today it will only buy you 1.2 Bolivianos- with this economic climate, many recent migrants now work just in order to survive. Amador states ‘it’s not like before- it’s not like the Argentinean dream. The currency used to be stronger, people used to be able to save. But now that the Argentinean peso is closer to the Boliviano - there are few opportunities.’

The Bolivians who come to work in Buenos Aires rarely integrate or are welcomed into the Argentine community; in fact, they face widespread discrimination and racism. They encounter widespread perceptions which label Bolivians as illegal, racially inferior and job stealing. Edson Veizaga, who lived in Buenos Aires for 13 years, states that this discrimination is in the collective consciousness. The media plays a big role in this issue: ‘Once I remember on Crónica TV, a very popular news channel, they said “Three people and one Bolivian died during an accident on a construction site.”’ He then tells how the word ‘boliviano’ is used as an insult or synonym of ‘dirty,’ ‘ignorant’ and ‘low class.’ Amador also tells me how even seemingly complimentary stereotypes conceal deep-seated racism. ‘They say the Bolivian is a good worker. That is a euphemism. What they mean to say is that they offer cheap labour. They will do any job at any price.’ Amador says that the Bolivian community is very closed, having created a tight-knit social network amongst themselves. He says that this insularity further hinders integration and that it is not just Argentinean society that is to blame.

A vast separation exists between the two communities: Bolivians live and socialise in different quarters to Argentineans. Famously, many Bolivians live in Villa 31, a shantytown which spreads out from the port of Buenos Aires. A Bolivian immigrant describes how he would never go to the Argentine bars because they discriminate against his countrymen – ‘They think you are just an Indian’, he says, and ‘this guy is ignorant; he’s a dirty negro.’

One display of traditional Bolivian culture in Argentina is the Fiesta of the Virgin of Copacabana, which is a large-scale gathering attracting around 30,000 participants and spectators, the majority of whom are Bolivian, held in the Charrua neighbourhood. At first glance, this would appear to be a potent symbol of Bolivians united, yet this is not necessarily the case. For example, the morenada is a way of displaying one’s economic status with the dominant protagonists being those who own or operate textile workshops, together with the Bolivian immigrant professionals and white collar workers who arrived in the 1970s and 80s. Their lavish outfits clearly set them apart, the most expensive of these being the super achachi, which comes complete with gloves, headpiece and careta (scepter), all of which together cost approximately US$500 to purchase and US$300 to rent.

This hierarchy found amongst Bolivians at the Fiesta of the Virgin Copacabana is indicative of real life, particularly between textile employees and their bosses. Painfully, despite their mutual discrimination and heritage, some Bolivians have reported that they prefer working under Korean bosses rather than Bolivian bosses, as they are seen as more reliable at paying their wages. Bolivians who progress to the stage of owning their own factories use the same methods under which they were exploited. Amador states, ‘It’s Bolivians exploiting Bolivians – it’s those people who arrived 10 to 15 years ago. They come to Bolivia and bring people over.’

Las Alacitas, a Bolivian holiday in which people purchase miniature versions of things they desire – anything from cars to university titles – which are then blessed by a yatiris, is celebrated by many Bolivians in Buenos Aires. The striking difference is that in Buenos Aires, miniature factories are are offered for sale, showing the celebrants’ desire to one day own a real, full-sized factory of their own. Often when immigrants arrive, it is on the basis of the promise that the factory owner will help them set up their own factory in the future. Amador admits that he at one stage considered setting up one of his own; however, he has decided against this route, as ‘people who’ve opened a workshop suffer from much stress – it’s a big responsibility to provide people with food and lodging, its a total commitment’. In order to make a profit, ‘you have to maintain an open workshop, working at all hours.’

The Bolivian migration to Buenos Aires is a curious one, from outside the main migration motive sees to be a search of better opportunities while working illegally in textile workshops under extreme working conditions. It appears inherently paradoxical - why do people choose to stay? Amador said that people choose to stay due to shame, ‘They feel they have left their country to build a future. They hope to return to the country and prove they have made a better life. What face will I give to my brothers, to my parents? The commonly held belief is that people who live in Argentina earn more.’ These immigrants’ mentality and silence on the issue clearly fuels this cycle of disparity. And so the cycle continues: Many more immigrants continue to chase the Argentine dream, even upon realising that it’s their pride which leads them to stoically endure their situation.

Download

Download