The soft red lights cast shadows on her supple body as she moves with the music. Her body melts into the pole, and every step she takes brings a cheer from the crowd. Her naked breasts bounce to cheesy pop music, and here I am, a journalist intern lost amongst this crowd of drunken businessmen and tourists, looking, slowly nursing my drink, a first-time visitor to one of La Paz’s best and most well-known strip clubs.

I look around at the regulars, each one mesmerised by the woman onstage, each one thinking she is dancing just for him and hoping for a cheap fuck at the end of the night. I watch as men in suits escort the girls through the crowd and backstage, while scantily clad women aged mostly between 18 and 25 persuade men to buy them drinks from the bar. One of the drunks near the stage is surrounded by women; he falls over and slowly stumbles back to his feet, then buys himself and the girls another round of drinks. I start speaking to a tourist sitting at the end of the bar. He slurs drunkenly, ‘Every time one of the girl gets someone to buy a drink for her she is given a bangle by the bartender. The more bangles she has on her arm at the end of the night the more money she gets.’ It’s not long before one of these girls is sitting on my lap, rubbing my chest and asking me to buy her a drink. My attempts to get to know her prove futile when every question I ask her is batted away with a smile, a shrug and a whisper. ‘Where are you from? ‘What’s your name?’ I ask. ‘It’s a secret’, she says. She walks away, looks back, breaks into a kind of half smile, and then sits on the next guy’s lap. Later on, the same girl asks me to spend a few hours with her in a small room upstairs. ‘I’ll give you a good price’, she says. I politely refuse.

A Bolivian I meet offers tales of his experiences in the strip club. ‘The men go because they are lonely, they are looking for company, and they try to numb themselves from whatever emotional hurt they are going through.’ He tells me how he visited a strip club after his heart was broken and he was looking for a distraction. Most of the girls in these expensive Bolivian clubs are from Colombia, Brazil and, above all, Paraguay. ‘One of these beautiful Paraguayan girls was looking really uncomfortable around the guy she was sitting with. She kept watching me. A few minutes later a waiter came up and told me this girl really wants to be with me, she wants to talk in private.’ He explains how the girls will sometimes choose the most decent-looking guy, or the guy who looks like he has the most money, and ask him to spend the night with her. ‘She was so young and beautiful. I found it a bit weird that at 19 she already had a boob job. I remember asking her why she worked in the strip club.’ He begins to fidget as he continues with his story. ‘She told me she didn’t have any other choice. She never knew her mum, and her dad was injured in a work accident and couldn’t work anymore. The compensation from the government in Paraguay is not enough to really live on, and she couldn’t get work apart from selling her body at the club.’ He looks at the ceiling and a soft sigh escapes his lips. ‘She looked so sad and said, “We should just drown our sorrows.” So, I bought a bottle of tequila for 500 bolivianos and all we did the entire night was drink and dance. I kissed her like she was my girlfriend and not just some girl I met in the strip club. She gave me her number before I left the club.’ He tells me about the house where the women live, how there are about 25 beds where they sleep. ‘It was so strange going to go pick her up for a date. All the women came to the door. They looked like they hadn’t slept in days, and they stood at the door shouting, threatening me and saying I’d better look after girl. She spent the entire date trying to get drunk, and I realised that she probably just wanted money from me and all I was looking for was some company.’

The sordid, drunken darkness of the club often masks the emotional unbalance of the men who frequent it, and the women who work it. The dim lights and lithe bodies are a fantasy beauty, for beyond them lies the swept stage and glimmering pole, equally empty, equally lonely.

'I am also a part of this society’

We are doing important social work . . . It is because of us that there are less cases of rape.’ So speaks Lily Cortez, president of OTN, the sex workers union of La Paz. OTN, along with its sister organization ONAEM, in Cochabamba, is fi ghting for sex workers’ rights. While prostitution is legal in Bolivia, sex workers are often not treated well and socially ostracised.

In 2005, residents of El Alto attacked a number of brothels and bars, ransacking and burning them in moral outrage, due to a belief that prostitutes ruin homes and spread disease. Cortez denounces this as hypocritical behaviour from of a society that enjoys prostitution clandestinely. Alina Rueda, a social worker at the CRVR clinic for sex workers in El Alto, confirms that Bolivian sex workers are for the most part in very good health, as by law, they are required to attend weekly health checkups. Rueda sees 500 workers a month pass through her doors. In the past two years, only one case of HIV infection has been diagnosed at the clinic, and less than 3% of her patients have been diagnosed with other sexually transmitted diseases

Unfortunately, sex workers are taken advantage of by the forces that are supposed to protect them. Paloma*, another sex worker advocate, says that the police sometimes extort money, usually 30 bolivianos, from women to complete their compulsory checkup. She also says that the police occasionally raid illegal brothels and offer the workers there a stark choice: a 300 boliviano ‘fine’ from the owner or free run of the brothel, its booze and its women for the duration of the night. The owners always choose the latter.

Illegal operations are a blight to sex workers’ rights organisations because, according to Cortez, society lumps legal and illegal sex work into the same pot and brands it negatively. But, Cortez rejoins, ‘Work is one thing, and crime another . . . I am also a part of this society.’ In fact, OTN and ONAEM campaign virulently against criminal sex activity because of the damage it does to their members’ profession. They receive anonymous complaints from sex workers who are mistreated in illegal establishments, and make public denouncements in an effort to close them down. They campaign against pimps and the trafficking of minors, and have helped deliver some trafficking victims to government shelters.

Evelia Yucra, a member of ONAEM, stresses that her organisation has helped give women back their sense of self-esteem, reciting a mantra invented at one of ONAEM’s first meetings: ‘Now I know who I am, I exist, other eyes have looked at me, I know that I can speak.’ At the moment, both organisations are, controversially, campaigning against the Bolivian Ley de Trata y Tráfico – the ‘Sex Trade and Trafficking Law’ – which they insist that, while it intends to protect minors, will damage opportunities for sex workers.

While OTN and ONAEM provide protection and solidarity to sex workers, they also paradoxically sustain a profession which most women admit they would rather not be engaged in. ‘Prostitution is consensual rape’, says Cortez. If she could make enough to live on with an office job, she’d leave sex work behind, and Paloma dreams of returning to her studies one day. They speak of finding strategies to deal with the pain that their daily work causes them. In El Alto I meet Gracia*, a shy woman in her forties, buried within a pale purple bowler hat and a voluminous pollera, who has been doing sex work for the past 20 years. Unable to read or write, she began sex work to support her family. Gracia finds it hard to speak about what she does, but says that her clients usually make her feel unhappy: they are drunk and use violent, offensive language, which she does not want to repeat. When she is feeling too downcast she switches brothels in order to get a change of scene. She is paid 30 bolivianos per client, 10 of which go to the establishment, and she is expected to service at least 10 clients a night. Rueda says that younger women might be expected to receive up to 40 clients a night, and that often men will pressure the sex worker to have sex without a condom, offering a handsome 100 bolivianos. Workers are sometimes robbed, but cases of extreme physical violence are rare. Nevertheless, both Rueda and Cortez can name workers killed by sexual violence. Violence can also extend to the family home: Rueda describes how a husband might fi nd out his wife is supplementing her income with sex work and then beat her. More sinister, some men force their wives into sex work, pimping them out and collecting all their earnings at the end of the night.

Rueda estimates that some 10% of workers are students looking for income support. The vast majority are single mothers who, hiding their work from family and friends, dream only of a better future for their children. Yucra, Gracia and Cortez are among the latter. Paloma, who has no children, says that she is inspired by the fi lm Pretty Woman – it comforts her through her day-to-day pain by showing a sex worker who is able to change her situation and find love. Rueda, though, is more cynical about this possibility: ‘Every now and again there are clients that fall in love with the sex workers, and they are able to leave the brothel work’, she begins, ‘but the utopia never lasts long. Eventually the man starts sleeping around again, and when the woman speaks up he says, “You’ve no right to complain, you’re just a bitch.” Usually they split up, and the woman returns to sex work.’

The need for OTN and ONAEM represents an inevitable reality in modern Bolivian society, helping women to survive it as best they can. While sex work typically involves the subjugation of the woman offering it, Yucra and her colleagues feel that the willingness of single mothers to sacrifice their bodies in this way is testimony to their profound strength. ‘Women are more responsible’, she says. ‘Women always think of others. We are the ones that take care of everything in the end.’

*To protect interviewees’ anonymity, some names in this article have been changed

Concepts of belleza in modern Bolivia

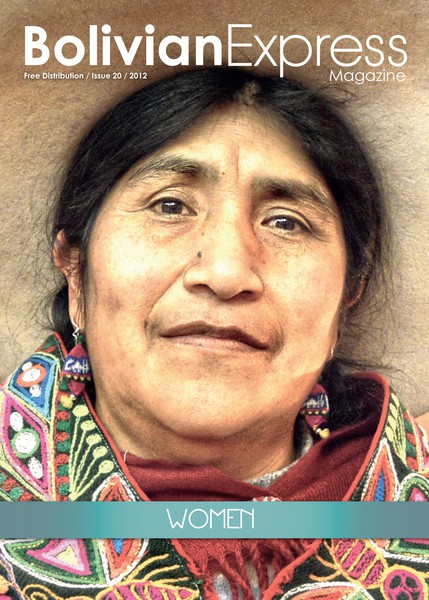

The crowd gathers, huddling together, holding balloons and unlit fi recrackers in Plaza Alonso de Mendoza in La Paz. They are all anticipating the parading cholitas decked in polleras and mantas and topped with bowler hats. As the proceedings begin, the contestants dance down the runway twirling their brightly colored skirts, looking like spinning cake toppers. Each young woman gets her turn to bask in the spotlight, jewelry sparkling while she answers questions in Aymara about the traditions of La Paz. Some of the women speak timidly, barely audible even as the announcer tries to coax them to enunciate into the microphone. These are beauty queens in a distinct Bolivian version of the beauty pageant.

The Cholita Paceña pageant, sponsored by the city’s cultural committee, selects a mujer de pollera each year, the embodiment of the traditional indigenous notion of femininity. But there is something else brewing than just a typical parade of physical beauty. Gloria Campos Ramirez, a fresh-faced young woman whose family lineage is studded with Cholita Paceña competitors and whose perfect skin shows no signs of the hard work of selling fi sh in Mercado Camacho, says, ‘Cholita Paceña is not about beauty. It is a way to show off tradition and our artisan crafts.’ The fully clothed contestants – no swimsuit competition here – of varying body types emphasize indigenous culture and traditional dress instead of the sexualised ideals of typically Western notions of female beauty. Unlike the Miss Bolivia competition, where those norms of beauty dominate, here the announcer keeps on remarking that this is not solely about physical beauty, and characterises the women as students and vendors instead of objects to ogle. By forming a space for cholita pride and giving voice to the women, the pageant combats the notion of Andean women as silent and unseen figures.

The celebration of the cholita aesthetic – a standard of beauty originating from the lower classes – is itself, though, income-dependent. The cost of obtaining the latest fashions for cholita women, unfortunately, opposes the objective of making the Cholita Paceña pageant a place absent of discrimination. Behind the stage, nervous giggles fill the space, a girlish buzz that becomes even more coquettish as the contestants swarm to get their photos snapped in poses that emphasize the expensive glimmer of their accessories. As Campos reveals to me backstage, the opulent intricacy of the dresses becomes the focus. She, along with her mother, rave about the pearls lining her manta. Pablo Flores, the pageant supervisor, says that each costume can cost up to a couple thousand bolivianos, a huge investment for the average Bolivian. Although the pageant is a celebration of a once-marginalized class, forming a space for pride while giving voices to the women and breaking boundaries in a country with a peppered history of colonial and neo-colonial rule, class and income disparity still mark the competition.

The diversity of the competitors becomes washed away as the presenter’s commentary attempts to unify them into a single type of woman. During the interview segment, the contestants are asked about their studies, jobs (which usually consist of working at comedores or in the market) and their support of the current government of La Paz. The focus on the food they sell and cook becomes a tool for the announcer to captivate the audience and create comic relief: ‘¿Vamos con hambre, no?’ The cholita becomes a static type, valued for her handicrafts and ability to feed and reproduce. The contest belies its goal of giving voice to the women by reducing them to this archetype. The cholita becomes a nonevolving figure, at once celebrated but at the same time reduced to a function by the contest, which purports to support indigenous rights.

On the other hand, the globally recognized Bolivian models and beauty queens are born and raised mainly in Santa Cruz, in the eastern part of Bolivia. Santa Cruz has become the go-to place for discovering Miss Universe and Miss World contestants in Bolivia. The women selected are light-skinned, tall, and thin, with perfectly pert breasts and long, wavy brown or blonde hair. They are trained at a young age in various modeling schools, and they attempt to capture the more Western aesthetic of perfection. In selecting women that exemplify this image, Bolivia portrays itself on the world stage as equal, striving towards becoming a part of the modern ‘first world’. For example, on boliviafacts. net, there is a top 10 list of ‘Super Hot Bolivians’, which includes this description of the No. 1 rated female: ‘As you can see, her eyes drip with that legendary Latina lust while her voluptuous body is the manifestation of the American (wet) dream.’ As Andrew Canessa writes in his essay ‘Sex and the Citizen: Barbies and Beauty Queens in the Age of Evo Morales’, ‘Miss Bolivia resolves the paradox in a fantasy: the body of a white woman with the accessibility of an indian woman.’ These beauty queens are well aware of this as they don traditional native dress and simultaneously present themselves beneath all the feathers and textiles as beyond the dark roots of their ethnicity. In 2004, the then Miss Bolivia controversially said, ‘We are tall, and we are white people, and we know English.’ Similarly, the concept of an indigenous ‘authenticity’ affects Cholita Paceña competitors. ‘I am a genuine cholita,’ says Emiliana, a contestant in her mid-20s, at the edge of the stage, slightly out of breath from dancing. The weight of this statement makes itself known when placed in the context of July 2007, when the winner of Miss Cholita Paceña was found to be wearing fake plaits. (She was subsequently stripped of her crown.) Both notions of beauty, mutually incompatible, entangle women and fragment their identities, reducing them to fl at, polarized characters.

In viewing the impact of the fabrication of beauty in Bolivia, the cultural and social politics are refracted, imposed, and read through the female form. The image of the female in the colonial outlook on Latin America originates around miscegenation, the sexual taking of the Indian women by the European in order to create a mestizo race. The market for both images has found its place in Bolivia. The thirst for the exotic and preserved tradition is desirable for both tourists and Bolivians alike, but modern sensibility tends to demand the lithe lomitas on display in Santa Cruz.

Where a pageant merely reinforces the same timeworn standards of femininity in Bolivia, the stakes are higher every time a woman passes down the pasarela. Each movement and each response becomes charged with a way of envisioning the entire country and the woman’s position within this expansive landscape. Each woman in each contest embodies a way of viewing beauty through a historical lens that surrounds her, but these forces are not the only influences. These women also bring and receive their own individuality. As one demure Cholita Paceña contestant who studies law told me when asked why she participates in the pageant, ‘I feel like a person.’ Her timid smile afterward revealed a sense of elation for finally having the chance to portray herself publicly to an attentive audience. As the only woman in her class, and, furthermore, the only woman wearing a pollera in her class, she is familiar with the whims of a male-dominated space. Her invisibility and visibility – usually out of her control at school – is firmly in her hands when she is in her gold outfit chispeando under the hot lights. She constructs her own feminine ideal. Beauty pageants are spaces in which notions of femininity can be heard, seen and contested, in which each contestant can challenge or maintain her conception of it as the lens to view the understanding of the Bolivian nation.

Download

Download