Bricks are being laid fast here in Bolivia. They are also being feasted upon. Just as fast by the Pachamama.

Their interiors, contrary to their gaudy exteriors have bare-naked walls devoid of pretty much anything aside from stucco. Visibly cemented, they appear naked with intestine-like uncovered pipes and septic tanks on display

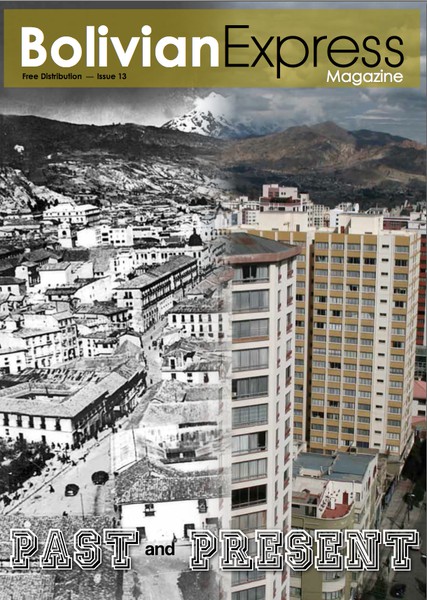

Bricks are being laid fast here in Bolivia. But if they are not laid carefully, the Pachamama of La Paz's infamous laderas will quickly swallow them up with the summer rains. Recent landslides which left hundreds homeless (and thousands at risk) are evidence of the need for architecture to respect topographical constraints. But Bolivians are adapting to their environment in all manner of ways; faced with the reality of finite resources, more consideration is being given to ecological factors, by adapting architecture to produce buildings which are sustainable both socially and environmentally they are making conservation viable.

At a time when social movements to defend the TIPNIS are in full heat, the Uyuni Salt Flats are increasingly parceled off into various mining contracts, and Cerro Rico is verging of collapse due to over-mining, sustainability problems which impact the whole nation have come to the public's attention. This implies respect and coexistence with the social and natural environments in which we live. Taking the TIPNIS protests as an example, the local imagination has fused the plight to defend indigenous ancestral homelands with a nationwide movement to protect the natural resources of a National Park. These social movements are mirrored by a subtle ecological revolution that is unfolding on a micro-societal level, at its most evident in the winding urban streets of the cities laid bare in the open: architecture in Bolivia.

As a discipline, Architecture has become increasingly permeable to pleas for sustainability. Ranging from tourist attractions to the interior design within homes in the city, these changes speak volumes about contemporary social attitudes. A case in point are the glaring, brightly painted buildings along Calle 6 de Marzo in El Alto. Monstrously glorious maisonettes now line the slopes of Bolivia's fastest growing city. These symbols signal the rise of a new economic sub-stratum within what has traditionally been a low-income social class; the rich comerciantes.

Wealth is no longer a reserve of the upper classes of colonial European ancestry. While it's true that many of Morales' measures as President have acted as socioeconomic levelers, wealth has not so much trickled down as been amassed and carefully managed by many astute businessmen and women from the bottom up. Cholitas, for example, can no longer be assumed to be impoverished housemaids or smalltime street vendors. By mastering the secrets of local and international trade (in line with Bolivia's tradition of socialistically-flavored consumer capitalism), many second generation indigenous migrants have turned into a substratum of wealthy merchants who have been instrumental in pioneering an architectural trend with an ecological bent – large edifices several stories high are springing up like green shoots across El Alto.

These multifunctional buildings' floors, often referred to as 'edificios multifuncionales', are constructed in this order: the planta baja is typically rented out for businesses, the second story for restaurants, the third for bars, pubs or salons, while the topmost floor is rented out as residential penthouses. Their interiors, contrary to their gaudy exteriors have bare-naked walls devoid of pretty much anything aside from stucco. Visibly cemented, they appear naked with intestine-like uncovered pipes and septic tanks on display. The types of investments that comerciantes engage in are intended to get more buck out of their boliviano with relentless pragmatism, a peculiar minimalism and 6 a form of upward mobility that is very much different from what I am used to in New Zealand.

Common and stark in the daylight, most of them are located on the road to Oruro. What is evident here is a Bilbao effect of sorts which dictates that 'great architecture should be the centre of urban space and development'. ""These fancy, grandiose edifices function as a status symbol among fellow comerciantes; to impress their peers with their wealth"", says Mario Landivar, a local businessman and social entrepreneur from La Paz. However, it's as much about the flash as the substance: the structure of these buildings allows them to cut energy costs by communal usage of facilities such as septic tanks, as opposed to building one for each tenant (and thus creating a more energy-consuming infrastructures). Thus a communitarian approach to urban planning with an ecological tinge has been created, albeit accidentally.

On a different social plane we encounter architecture which seems worryingly oblivious to its surrounding natural environment. Taking a stroll down either Vino Tinto or Pampahasi you would be hardpressed not to decode it as a metaphor for the metropolis's wealth disparity. The bare, often incomplete brick-red houses are perched precariously along the laderas of La Paz. They grow exponentially with urbanization, and are often built on unstable soil: most of them face the danger of annual landslides. However, change is in sight. These mass migrations are also a sign of upward mobility within the village community, and NGOs have already begun laying the foundations for ecologically sustainable mobility. For the past decade CARE International has been supporting small-scale economic development throughout Bolivia and devising environmental sustainability education and landslide recovery strategies. One of the efforts involved the invitation of prominent Japanese architect Hiroshi Hara to La Paz last year to exhibit prototypes of his proposed houses of small, interconnected towers designed to withstand earthquakes and landslides.

Jesus Rodriguez, a local architect, tells me ""These independent blocks work in a different, more balanced way when the earth moves in unstable areas. The house won't be affected as much by shifts in soil, not like what happens to homes built in one piece that is heavier. Made of lighter construction materials, Hara's design features 3 small towers, connected by bridges that are energy- efficient and easily constructed. Architecture students without extensive experience in construction built this in two months with the help of other people. That's part of Hiroshi Hara's idea, that normal people can build their own homes. Rodriguez and colleagues are working to bring down the cost of the home, which at around $25,000 is far more than most of the existing houses.""

Regarding its reception, Michael Bumüller, a local architect, said that there was ""little to apathetic acknowledgement"" of his visit. Hara's efforts were not fated to be a permanent fixture along the city's skyline. He thinks that it is a combination of insufficient capital by the poor migrants along with a strong resistance to foreign influences that have hampered the adoption of these techniques. It is paradoxical that foreign influences of this sort are seen as an affront of indigenous identity and culture, as in any case local architecture is already heavily influenced by Spanish styles since the colonial era, Bumüller remarks.

Ayllu is a state-backed programme which seeks to persuade barrio residents to adopt sustainable building strategies by promoting a series of manifestos and proclamations that ensure respect for their own territorial organization. Through these documents, communities such as Jesus Machaqa have sought to take control of their surroundings by living in accordance with the 'suma qamaña', an Aymara metaethical principle of 'living well', by achieving a balance between the spiritual and material world, as well as coexisting with all life-forms.

More effort than ever before is put into sustainability due to raised awareness about the sensible use of resources. Worldwide trends including ethical consumerism and green fashion are also aiding in this process. Although the dizzying vortex of La Paz is separated by incongruent surprises from both the modern and ancient worlds, one must look, read, and pry deep past anachronistic brick buildings, outof- place-Moroccan medinas, pass over the romantic silhouettes of Gothic cathedrals (and of coursethe lingua franca of any burgeoning metropolis- the modern 'decons' that monopolize the city) and into these marginal barrios to pick out signs of burgeoning ecological revolution that is going on beneath the surface. Or should I say, within the Pachamama?

By all accounts, Franz Tamayo lives on. Where the founding father of Bolivian letters used to contemplate the snow-capped Illimani ('Two giants gaze upon each other', an anecdote would have him say), there now spring countless buildings bearing his name. On the Andean slopes, books and their authors are no mere relics of the past. Neither are several historical events that have shaped the Bolivia of today - they still resound in the way Bolivians view the world. Here is a crash course in the country's national mythology – as seen by the most cherished novelists between the Andes and the Amazon.

The Independence (1825)

Nataniel Aguirre, Juan de la Rosa

With its war of liberation lasting from 1809 to 1825, Bolivia was the first of Spain's Latin American colonies to proclaim independence - and the last to achieve it. The fighting resulted not only in the creation of a new republic; it also gave birth to what the Spanish critic Menendez Pelayo proclaimed to be 'the greatest South American novel of the nineteenth century'. Curiously enough, the authorship of Juan de la Rosa is still controversial. Usually attributed to the Cochabambino Nataniel Aguirre, it is a fictional account by 'the last soldier of the Independence'. Two narrative voices intertwine: that of the adult Juan, narrating the decisive moments of the war; and his childhood self Juanito, looking for his unknown father. A classic tale of searching for identity, vivid fictional characters and a gripping historical background – the 'benchmark novel' of Bolivian literature seems to have it all.

War of the Pacific (1879-1883)

Alcides Arguedas, Pisagua

A brief visit in La Paz's Museo Litoral captures the sense in which Bolivia's loss of its coastline to Chile (and hence its access to the sea) has become a national obsession. Formally relinquished after a bitter war which culminated in 1884, the country's loss of access to the Pacific is still today seen as a national tragedy. Arguedas' work shows the beginning of the end: the battle of Pisagua, providing Chile with a foothold from which it launched its devastating Tarapacá campaign. Short and succinct, it provides a good insight into one of the country's most bitter national narratives.

The tin fever (late 19th century – 1913)

Fernando Ramirez Velarde, Socavones de angustia (Tunnels of Anguish)

The early 20th century tin boom made fortunes, toppled governments and changed Bolivian society forever. It saved the country's economy from collapse as silver mining declined, created a caste of tin barons (of which Simon Patiño remains the most legendary) and prompted the 1899 revolution which established La Paz as the effective seat of power. There is, however, a darker side to this picture. Ramirez Velarde's Socavones de Angustia traces the fortunes of a displaced Quechua family, forced to seek employment in the new industry. A sweeping panorama of contemporary Bolivian reality, it explores the hardship of the mining pueblos, the social condition of indigenous people and an emerging political consciousness that transformed Bolivia for years to come.

The Chaco War (1932-1935)

Augusto Cespedes, Sangre de mestizos (Blood of the Mestizos)

Bolivia, too, has had its Lost Generation. The 'War of Thirst' over the frontier with Paraguay in the Chaco region's arid wilderness proved a national trauma not unlike that experienced by other nations during the First World War. Circumstances were similar: disillusionment surrounding the war's aims (as the Chaco's oil deposits turned out to be nonexistent), and a level of casualties unheard of in the country's history. Much like after WWI, a legacy of bitterness ensued, permeating the work of Chaco's greatest chronicler Augusto Cespedes. His Sangre de Mestizos is an array of personal histories marked by the catastrophe. With its psychologically complex and multi-layered characters, Cespedes' book is a fascinating (to borrow a title of his later work) 'heroic chronicle of a pointless war'.

The 1952 revolution

Oscar Cerruto, Ifigenia, el Zorzal y la Muerte (Ifigenia, the Thrush and Death)

'The National Revolution' was a broad-based rebellion which gave power to the left-wing National Revolutionary Movement (MNR) and brought about wide-ranging reforms to the Bolivian political system. The MNR coup fed into an atmosphere of popular unrest and hunger strikes in angst-ridden La Paz. Large sections of society were demoralized after the Chaco war by an incumbent government thought to be loyal only to the upper classes, as well as a rigged presidential election in 1951. Oscar Cerruto, however, is no painter of mass demonstrations and civil unrest. His hero, an ordinary Bolivian anxious about the coming upheaval, stumbles between the real and the imaginary as the capital's streets fill with armed protesters. A fine example of Bolivian magical realism, Ifigenia el Zorzal y la Muerte is also a haunting psychological study of one man's anguish.

The 1990s

Juan de Recacoechea, American Visa

Generals and martyrs aside, no list of books can be complete without the odd detective novel. American Visa, however, is no mere tale of murders and mysteries. The story of Mario Alvarez, a Bolivian teacher desperate to get to the US, weaves criminal intrigue with a deeply satirical portrait of contemporary Bolivian society. Crooked officials, displaced desperados and kind-hearted prostitutes cross paths in the bleak urban landscape of the capital - the author's answer to the Latin American cliché of magical realism. In de Recacoechea's La Paz, as the afterword states, 'the only thing magical is to make ends meet'. A play on classic noir fiction (Alvarez, a Chandler fan, won't flinch from means deployed in the latter's books to get the muchneeded money), it is one of the few Bolivian novels from past decades to win acclaim in the Anglophone world. While the hero struggles to reach the United States, there is every reason for his American readership (and why not, the rest of us too) to follow him along the way.'

The Future?

Alison Spedding, De cuando en cuando Saturnina (Saturnina From Time To Time)

Chances are that in 2086 Bolivia will no longer exist.In what is said to be the first science-fiction novel written in an Andean Spanish vernacular, the country has been renamed to Qullasuyu Marka, embraced its indigenous heritage and closed its doors to any hint of foreign influence. In an autocracy revolving around rural, coca-growing communities, several women tell stories of revolution, repression and broken hopes. Among them is Saturnina Mamani Guarache, a legendary Andean guerillera imprisoned as leader of an indigenous anarcho-feminist organization which could threaten the established order. The British-born author juggles futurist cybernetics and the ancient Andean cosmovision with astonishing ease, sketching a vision as disquieting as it is fascinating.

Daniel Caplin investigates the historical and political texture of Bolivia's iconic indigenous flag.

In its Constitution, Bolivia is described as a plurinational state. This is an apt description seeing as it does, after all, encompass a wide variety of cultures, peoples and tribes: from the indigenous descendants of the original inhabitants of the territory such as the Incas, to criollo descendants of the Spanish colonizers (not to forget the increasingly ubiquitous gringos). Since Evo Morales' rise to power, he has juggled champining the interests of the indigenous peoples while attempting to unite a nationally fragmented Bolivia. Notably, he has enshrined the Wiphala as an official second national flag in the Constitution. Far from uniting the indigenous people of the plurination under a (literal) tapestry of colour representing each nation, this move has been the focus of widespread controversy. There is no doubt that for a large number of Bolivia's indigenous peoples today, the Wiphala constitutes a vivid symbol unmistakeably associated with the campaign for greater equality and the recuperation of identity which rose Evo Morales to the presidency, and which the MAS has continued to associate itself with during his time in office.

But where does the Wiphala come from? Is it, as many followers would assert, a rescued artefact dating from the Incan era, or is there more to the flag's elusive origins than first meets the eye? The government, backed up by historians such as Fernando Huanacuni claim that the Wiphala is a rescued relic, much like the Andean Cross or Chacana, which they substantiate with evidence such as ancient Wiphala fragments found on pre-Columbian ceramic vases of the Tiwanacota culture. Supporters of this theory cite the fact that during the Spanish invasion and occupation of Cuzco in 1534, Spanish chroniclers documented a multitude of objects similar to the modern day Wiphala, using the seven colours of the rainbow and which shows that the iconography of the arco-iris was an integral part of Incan symbology.

However, the Wiphala has also faced much criticism regarding not only its origins but also its political role within the indigenous movement. Firstly, the idea of the bandera or flag as a national icon is typically understood to be a European phenomenon. Furthermore, although there is scant evidence of a rainbow flag in Incan records, there is in fact evidence of its appearance in Spanish iconography from the same era: pictures of two angels bearing a standard that is suspiciously similar to the Wiphala.

The second (and perhaps less frivolous) controversy is that there are many who feel that the Wiphala, meant to represent all the indigenous peoples of Bolivia, falls somewhat short of this goal. The Wiphala, it is said, is a predominantly Aymara symbol – even an Andean one at a stretch- and other indigenous groups do not always feel included in its tapestry. Nations from the culturally and ethnically distinct Amazon regions of the country, such as the Guarayos and Moxeños, share little history with the aforementioned groups. Given this limitation, and the fact that for the non-indigenous population the Wiphala is not connected to their history, the pressing question remains: should it really be a nationally recognised flag?

This question is not easily answered; for the majority of people a flag or national symbol is a political artifact whose importance lies in the emotional connection between it and the people. When it is found to be misplaced or incomplete, it can have the opposite effect of fragmenting the imagined community or communities which underwrites the state. This was reflected in the comment made by the ex-President and historian Carlos Mesa, who said to BBC Mundo that ""the Wiphala represents only part of the country, it stands for the Andean indigenous world which is predominantly Aymara, though also Quechua. It isn't an expression which denotes the totality of the Bolivian population"".

In Santa Cruz and more generally the East of Bolivia this feeling has been manifested in a reluctance to raise the Wiphala on official occasions. The reluctance is certainly demonstrative of the Wiphala's failure to relevant on a national scale, but there is also the question of oppositional politics. The Governor of Santa Cruz is a prominent member of the government's opposition and so it is worth considering the possibility that his party's hostility toward the Wiphala is simply a reflection of their hostility towards Evo's government in general.

Nevertheless, the Wiphala's symbolic and political importance is hard to overstate. Since its birth (or resurrection, depending upon your viewpoint), the Wiphala's resonances have been powerful and widespread. As a political symbol in the campaign for indigenous rights it has represented the recuperation of the indigenous peoples' identities and dignity against a society that was previously stuck in a neo-colonial rut of racial inequality. Its official recognition in the Constitution, (refer to Article 6), only went further to reinforce the fact that Bolivia's politicians and state apparatus were no longer capable of oppressing its native populations.

Whether you choose to believe that the Wiphala is an ancient symbol or a political people its presence is undeniable. It is an emotive, highly aesthetically pleasing symbol; political for most and historical for many, but most importantly, it is here to stay.

- The Wiphala plays an integral role in Andean everyday life. In communities of the altiplano it is raised at meetings of the Ayllu, weddings, births of children, after completing construction works.

- As an Andean symbol, ideologists of traditional cosmovision have seen far more in the Wiphala than its superficial and political meanings. They variously claim that the squares and rainbow palette represent the harmony, organisation and unity of the system of the Quechua-Aymara world-view, that each square of the Wiphala represents a nation of the pre-colonial era, and that for every colour there is a corresponding metaphysical significance. Just a few examples are: Blue: cosmic space, the infinite (araxa-pacha). Astronomy and Physics: natural law. Purple: Andean politics, ideology, community power and the harmony of the Andes. Orange: Society, culture, procreation and preservation of the human species.

Download

Download